Accepting credit card payments at a food truck, building a website for an online store, or figuring out how to make legacy payment processors work with a new type of commerce were difficult problems to solve before Stripe, Block (formerly known as Square), PayPal, and Adyen came along.

As a merchant, you’d first have to work with a legacy processor or a middleman broker who could provide you access to a processor. Then you’d deal with the banks, the credit card networks directly, and probably a jumble of other services that were often poorly explained, packaged, and sold by various third parties. The slew of regulations, hundreds of interchange rates dependent on a variety of factors including card type, merchant type, charge amount, and so forth, as well as huge antifraud measures making regulations more than triple what they once were made accepting credit cards an incredibly complicated and poorly explained process.

For an e-commerce business, merchant acquirers were difficult to work with. Most of them were still operating mainly in physical retail and didn’t possess the necessary technology or the knowledge to take on a new type of commerce. Signing up to a merchant account was cumbersome and opaque and some required minimum monthly revenue and a long application process. It was hard to know what your rates would be, how much the technology would cost, what kind of service could be expected, and whether or not the processor technology would even integrate well with your e-commerce implementation. Payfacs eased the burden but still required significant time and financial investment. If a merchant wanted to expand to new markets or integrate another payment method, it would require another inconvenient process.

Things have evolved fast for the past ten or more years. When Stripe Payments came along as a modern PayFac focusing specifically on digital card payments, it changed the game from opaque to transparent by focusing on the merchant and, almost more importantly, the developer first. Stripe made signing up as a merchant simpler, faster, and more transparent and the life easier for the developer as to how they integrated with the API. Almost regardless of technical ability, Stripe had invented a framework based on a few lines of code that allowed the merchant to get up and running quickly.

But while it seems like Stripe came in to streamline the entire payment ecosystem from the perspective of the merchants and their customers, it wasn’t really doing the heavy lifting of processing the transactions other than collecting and forwarding them upstream to those (i.e. Chase Paymentech) that would clear the funds. If you imagine the payment stack with the issuing banks on top and the merchants and shoppers at the bottom, Stripe swooped in right in the middle and made life a whole lot easier downstream. As merchants signed up to Stripe, they essentially became sub-merchants underneath Stripe’s main merchant account so they could bypass a lot of the headaches associated with things like AML and KYC regulations, application processing, and underwriting. That way they could save the setup complications and simplify the entire process around accepting, managing, and expanding payments.

On the other side of commerce, the physical side, Block also came along as a PayFac with its famous mobile payment processor for small businesses that operated on the go, such as food trucks, plumbers, and so forth. With a small and convenient adapter that the merchant could plug in a phone’s headphone jack, which Block gave the merchant at a loss, the company could scale at a rapid pace across mobile and brick-and-mortar businesses alike who otherwise wouldn’t go through the hassle of setting up a payment system the traditional way. Before Block, small merchants would have been approached by a commissioned salesperson working for an ISO who would try to sell the merchant a heavy POS install for thousands in setup fees that would need to be regularly maintained by the ISO itself.

Scale on the brick-on-mortar front turned into high gear once Block launched Square Stand, a physical stand that transformed iPads into cash registers on which the company could slap on inventory management, analytics, online ordering, gift cards, capital management tools, and so forth. Square Cash, later renamed Cash App, then launched as a P2P platform, Square Payroll allowed SMEs to easily manage payrolls, and the open platform API allowed for customization at the merchant level, evolving Block into a full suite of financial business software to the physical SME market.

As Stripe and Square invented a new layer of the payment stack, what went on upstream of the stack became more hidden from many smaller merchants’ eyes. As payment setups turned convenient, merchants were more than willing to let each of those FayFacs skim a few points off the top of each transaction rather than going through the hassle of making all the connections to the card networks themselves—but larger enterprises still would since a few basis points could equal millions in incremental sales.

Given the many layers, players, applications, and dynamics that involve everything payment, it’s no wonder that the payment ecosystem can be a difficult thing to wrap one’s head around. I’ll explain with two examples: one from the demand side and one from the supply side.

From a shopper’s standpoint, the transaction flow looks like the simplest thing in the world; They insert their card—which they got from a card issuer, typically a bank—in a POS terminal to purchase for a good or service (or enter their card information on an online payment gateway), they get the goods, and the amount paid is taken from their bank account within a couple of days.

But the transaction flow behind it all is, of course, more intricate than that. What really happens is that after the initial touch of payment, the shopper’s information is transmitted to an acquirer processor (sometimes the acquirer and processor are the same entity) who performs the relevant initial risk management checks before routing it further to the proper card network, e.g. Visa, Mastercard, UnionPay, Amex, and so forth. These card networks set the rules concerning the processing of transactions and are the backbone of the electronic payments system and so they require a bunch of data points from the processor before sending an authorization request to the issuer processor of the card issuer (issuer processors are to banks what merchant acquirers are to merchants) who does the necessary identity and compliance checks on the shopper’s bank account. Assuming these checks validate, the issuer tells the card network to accept the payment and the card network then forwards the authorization note to the acquirer processor. The acquirer processor then sends the authorization note to the POS terminal / online gateway, enabling the merchant to proceed with the transaction and provide the shopper with a confirmation and a receipt. The actual settlement happens at a later point in which the merchant sends a capture request to the acquirer processor who routes the capture to the respective card network. The card network transfers the request to the appropriate card issuer who informs the shopper of their transaction by posting it on their statement. The card network then calculates the net settlement positions for the acquirer processor and the card issuer, advises both parties of the amount, and submits a transfer order to a settlement bank. The settlement bank acts as a facilitator for the flow of funds between the acquirer processor and the card issuer. Lastly, the acquirer processor transfers the received funds to the merchant’s account.

That described the flow from the demand side. On the supply side of the transaction, the cost flow and distribution look something like this: First, fees are charged to the merchant as a percentage of the value of each transaction (called the Merchant Discount Rate, or “MDR”). The MDR of 3% or whatever is what’s split between the players covered above with the card issuer covering the majority of that (about 70%) as interchange fees. On top of these interchange fees charged from the card issuer (via the card networks), the card networks charge payment networks fees (in the form of assessment and transaction fees) which comprise about 10% of the MDR. These fees are all charged to the acquirer who then passes them on to the merchants by adding a little mark-up and charging the full amount—the merchant’s own incurred costs plus the mark-up—as a “settlement” fee. Since the acquirer contracts with third parties to facilitate the interchange of funds between the issuer and the merchant, it’s also contractually the acquirer that is responsible for ensuring that these services are performed to the acceptance of the merchant, and so the mark-up that the acquirer charges to the merchant is there to compensate for this exposure. The merchant is perhaps also charged processing fees for letting the transaction pass through the gateway or POS payment provider. After the transaction is complete, the acquirer then remains liable to settle eligible chargebacks with card networks. To cover for this inherent risk, the acquirer withholds funds from the payouts to merchants (this reserve is called the “Merchant Potential Liability” (‘MPL’) on the balance sheet).

Given the intricacies of this entire system, one might ask themselves what it is that drives one payment service provider to grow faster than the other and attract all the merchants. Looking at the payment stack, differentiation matters the closer to the shopper a provider is. For example, as for the payment gateway, merchants want what they themselves find the most convenient for the right price and they want what shoppers are either accustomed to or find the most intuitive to make the shopping experience as seamless as possible. Shoppers may care about their purchasing experience but they do not care which acquirer underpins the transaction. So as you move up the payment stack, it’s not differentiation that matters, but price and reliability. Take for example processing that companies such as First Data, Global Payments, and Worldpay offer. There’s no feedback mechanism evident in terms of network effects at merchant processors because they essentially provide a commodified service. Merchants don’t care what payment processing they use and they generally don’t care what processor other merchants use. You really only find strong network effects at the top of the stack with the card networks where shoppers use specific payment cards like Visa and Mastercard because every merchant accepts them, and vice versa.

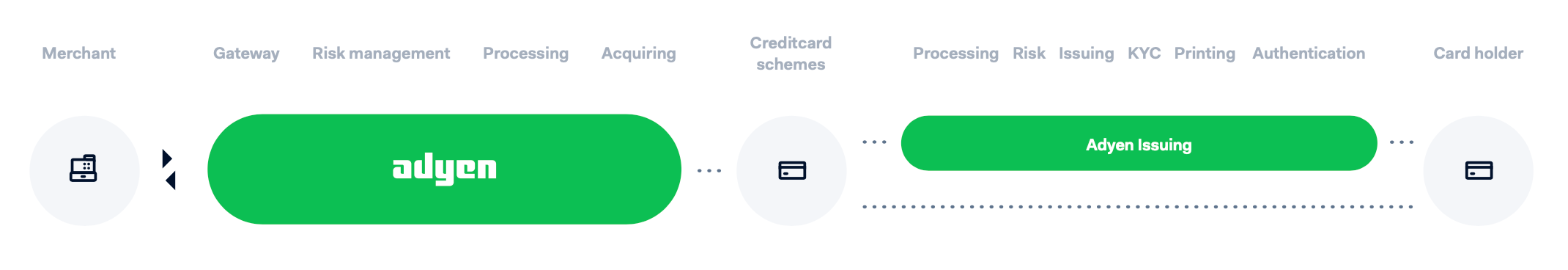

By integrating the full payment stack all the way from merchant to card networks—from the gateway to risk management, processing, acquiring, and settlement—Adyen has taken on quite the challenge of essentially competing with all of the above incumbent payment service providers (PSPs) at once. But the company has been on a growth tear for years because it fulfills exactly the points I mentioned by integrating the entire stack. It offers extreme convenience at the merchant and shopper level while passing on the cost savings it gets to the merchants by connecting them directly to the card networks through a lower take rate. Like Stripe and Square, Adyen is merchant-centric using first principles development (Adyen is literally Surinamese for “start over again”) to cut out the banks and provide full transparency in allowing merchants to measure how it connects the merchant directly to the card network.

Although, it’s not an easy thing to swoop in and take business away from behemoths just by coming up with better tech. While incumbents may not have Adyen’s innovational prowess, what they do possess are major distributional advantages. Legacy acquirers, long dependent on bank referrals and traditional ISOs for distribution, have essentially built their moats around the distribution system alone. For instance, Worldpay, which was previously owned by RBS, sourced almost all its volumes from its parent bank. When distribution comes easily, you don’t have to worry much about innovation, which is what incumbents have lived well off on for decades.

But the distributional game has changed and so has the reliance on technology for competitive advantage—a trend that has happened gradually for about the past decade.

Modern players like Stripe, Square, PayPal, and Adyen paved the way. Instead of using brute-force push strategies to bring in merchants, they opted for horizontal pull strategies. Instead of relying on pushy sales relationships with powerful banks and ISOs, they scaled to impressive volumes by focusing first on merchant (and developer) needs through a combination of pull and ISV partnerships. This is a secular industry trend. As software is swallowing up major parts of business management, ISOs with their generic payment solutions become dis-intermediated by business management software, natively integrated with payment solutions that meet the idiosyncratic needs of specific verticals. The fact that an ISV can use Adyen’s platform to integrate payment into a client’s business management software with no third-party dependencies and a complex patched together system allows it to optimize every stage of the payment flow across unified commerce much more efficiently.

Incumbents have responded by attempting to dig even deeper into their distributional moats, creating payment behemoths of huge scale by merging left and right—Fidelity National with Worldpay, Global Payments with Total Systems, Fiserv with First Data, all happening two years ago in 2019. This is in itself not a bad thing. The merchant acquirer industry is prone to consolidation because, by merging, acquirers can spread their transactions over a smaller fixed costs base and take more advantage of cross-selling opportunities, entrenching a cost-competitive advantage.

But whether it’s eventually going to be enough to withstand the technical forces from modern PSPs is up for discussion. Payment mega-mergers have led these behemoths to two main constraining positions. First, they have substantially tightened their distribution arrangements with financial institutions. Second, pushing for distribution and scale through acquisitions has bogged them down as they now struggle with a jumble of different payment architectures and software layers that makes it difficult to scale new features across channels and geographies. What looked like attempts to widen their moats—global strategic acquisitions—have instead left them with ever more integration issues that ever more of their engineers need resources in maintaining rather than pursuing innovation. The result is that maintaining and integrating legacy systems overshadows their willingness to think long-term.

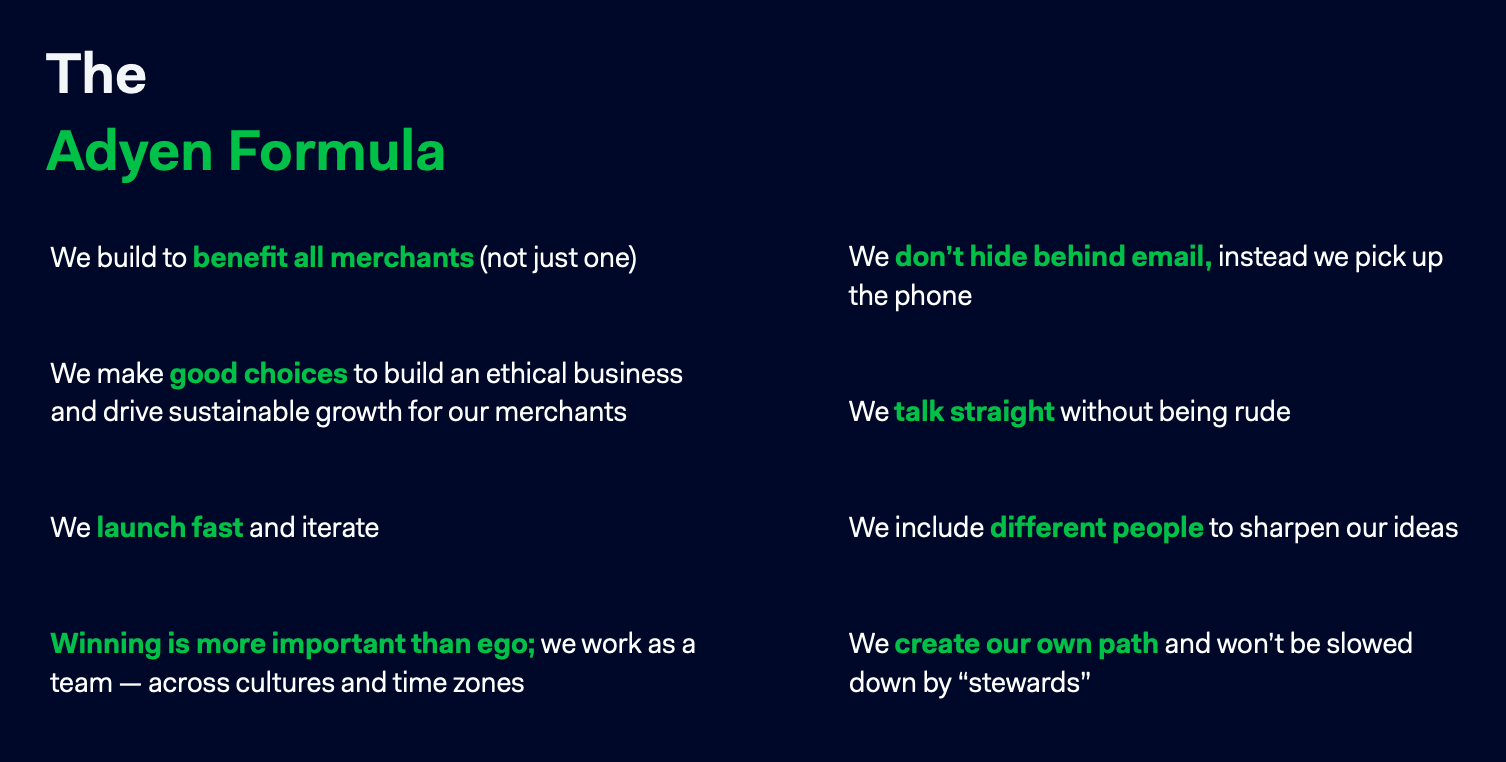

In contrast, Adyen’s entire system is built bottom-up and the company hasn’t done a single acquisition since its founding in 2006. Rather than being a post-merger integration business, it’s a complete people management business. Out of Adyen’s operating expenses—which are in itself measly—wages, salaries, and employee benefits comprise 63%, heavily leaned towards engineering capabilities. Adyen divides bottom-up workstreams into product, technical, and commercial staff who cooperate to efficiently prioritize a merchant’s needs based on what’s named the “Adyen Formula”. The Adyen Formula consists of eight principles that aim to foster speed and agility and guide how the company recruits, grows, and retains employees.

The engineers have worked fast. In global merchant acquiring, Adyen and Worldpay (owned by Fidelity National) are today the ones who are most technically inclined to handle hundreds of different payment methods in hundreds of different countries using hundreds of different currencies. But there’s quite a difference between the two companies. Through Adyen, multinational enterprises can consolidate dozens of local acquiring needs into a single back office. The solution is easy to integrate and merchants achieve higher authorization rates than with incumbents who rely on patchworks of dozens of local systems. Whereas Worldpay functions as a patchwork of disparate, region-specific platforms, Adyen’s single system is built in-house and bottom-up. So whenever Adyen rolls out a new add-on to the existing system, it can do so across all regions simultaneously as opposed to a multi-system acquirer like Worldpay that has to customize the add-on to each infrastructure, effectively doing the same work a whatever multiple of times. Given that the evolution of the payment industry is ever-changing (and at a rapid rate), Adyen finds great strength in its speed and agility to react to market developments. Like with operating expenses, this fact leads over to maintenance of which Adyen’s single platform requires very little compared to peers, allowing Adyen to earn almost double the peers’ EBITDA margins (Adyen earns ~60% while peers are in the mid-30s). In fiscal 2020, Adyen only spent 3% of net revenue on CapEx while Worldpay spent 36% of revenues in 2018, the year before it was acquired by Fidelity.

Adyen Unified Commerce

The pandemic pushed the necessity of a holistic view of payments to new heights. Unified commerce, in which a merchant pursues an omnichannel shopping experience, went from nice-to-have to need-to-have. In the majority of industries, merchants can no longer afford to have only one sales channel. Shoppers want a unified and seamless experience across channels and they don’t care about whether that is happening online, by curbside pick-up, or through in-store purchases either by assisted checkout or self-service checkout. It’s just part of the new reality and Adyen’s unified platform is foundational to this shift. For instance, through Adyen, a shopper who has purchased something from a merchant in-store can be immediately recognized and use one-click payment when they shop again on the merchant’s online store—a simple feat that is hard to achieve without a unified platform.

Convenience is a durable competitive advantage because it’s not easy to achieve for the merger integration reasons I’ve discussed. But there’s also a data advantage inherent in the bottom-up developer approach. Because legacy acquirers operate disparate systems with each data collection activity siloed, the end result of that is information attrition and lower authorization rates. In contrast, due to Adyen’s common back-end infrastructure for authorizing, Adyen’s transaction data flows horizontally across all channels so that, for instance, more high-ticket purchases or other unusual but legitimate transactions are instantly approved when they may not be on another platform. And this advantage gets enforced as the industry trend towards SCA, supported by the PSD2 regulation coming into effect across Europe, becomes top of mind for networks. Adyen’s machine learning-driven 3DS2 feature leverages the data throughout the platform to significantly combat fraud rates across SCA transactions.

Adyen’s data and infrastructure advantage really is the shining part of the growth story. Authorization rates are a dealbreaker, especially so for large enterprises to which a marginal authorization rate improvement could be equal to millions in extra sales. Additionally, in contrast to legacy acquirers’ passive stance on whether merchants grow their top lines, Adyen’s RevenueAccelerate service and suite of data tools help merchants recover otherwise lost transactions by, for example, creating frictionless shopping experiences in which shoppers are being asked to authenticate only when needed, routing transactions through the best-performing processing route to achieve the highest conversion rates, sending the right payment data for maximum approval rates at each issuing bank, and, via machine learning, finding the best days and times to retry a shopper’s failed payment. There’s no way to know for sure whether Adyen commands industry-leading rates of transaction authorization. But given that Adyen has taken as much share as it has from incumbents, it seems likely that it does.

And Adyen keeps grabbing its fair share across unified commerce. In H12021, POS volume doubled year-over-year, making up a current 11% of total processed volume, and attracting a variety of Silicon Valley and household names to the customer fold, including Airbnb, Spotify, Nivea, Farfetch, SHEIN, LVMH, McDonald’s, American Eagle, and Slice. By selectively serving large enterprises (as of fiscal 2020, the top 10 merchants represented 38% of revenue) and working closely with them in adding new channels and/or expanding across geographies, Adyen grows as the merchant grows while creating sticky relationships and increasing the wallet share. Those factors result in that most of Adyen’s annual growth (consistently >80% from each half-year period since the IPO) comes from the growth of merchants already on the platform. <1% of Adyen’s volume churns on a half-year basis.

From a bottom-up standpoint, Adyen and Stripe share similarities. Like Adyen, Stripe has grown organically and spent all its efforts into removing the hassle that merchants go through when they want to integrate multiple payment systems. But the similarities fizzle out if you look closer where you see that they take very different approaches in doing business. Through its vision of “growing the GDP for the internet”, Stripe has always been an e-commerce first business, optimizing for rapid onboarding and easy integration for any property on the Internet. With its deep Silicon Valley roots, Stripe wants to remove red tape weighing down on the legacy payment industry. But by focusing on offering a broad suite of services to wrap around the core payment experience, Stripe seems interested in everything but the payment processing component and the result has been that Stripe caters to the huge SMB market while steering clear of large enterprises who want more control of the full stack. In contrast, Adyen is laser-focused on payment processing and does everything it can to improve that core element of its offering, catering to the mid to large enterprise market.

So there’s this difference between Adyen and Stripe. Adyen is a full-on global payments platform, integrating the full payments stack—gateway, risk management, processing, issuing, acquiring, and settlement—with fees almost exclusively earned from processing and settlement…

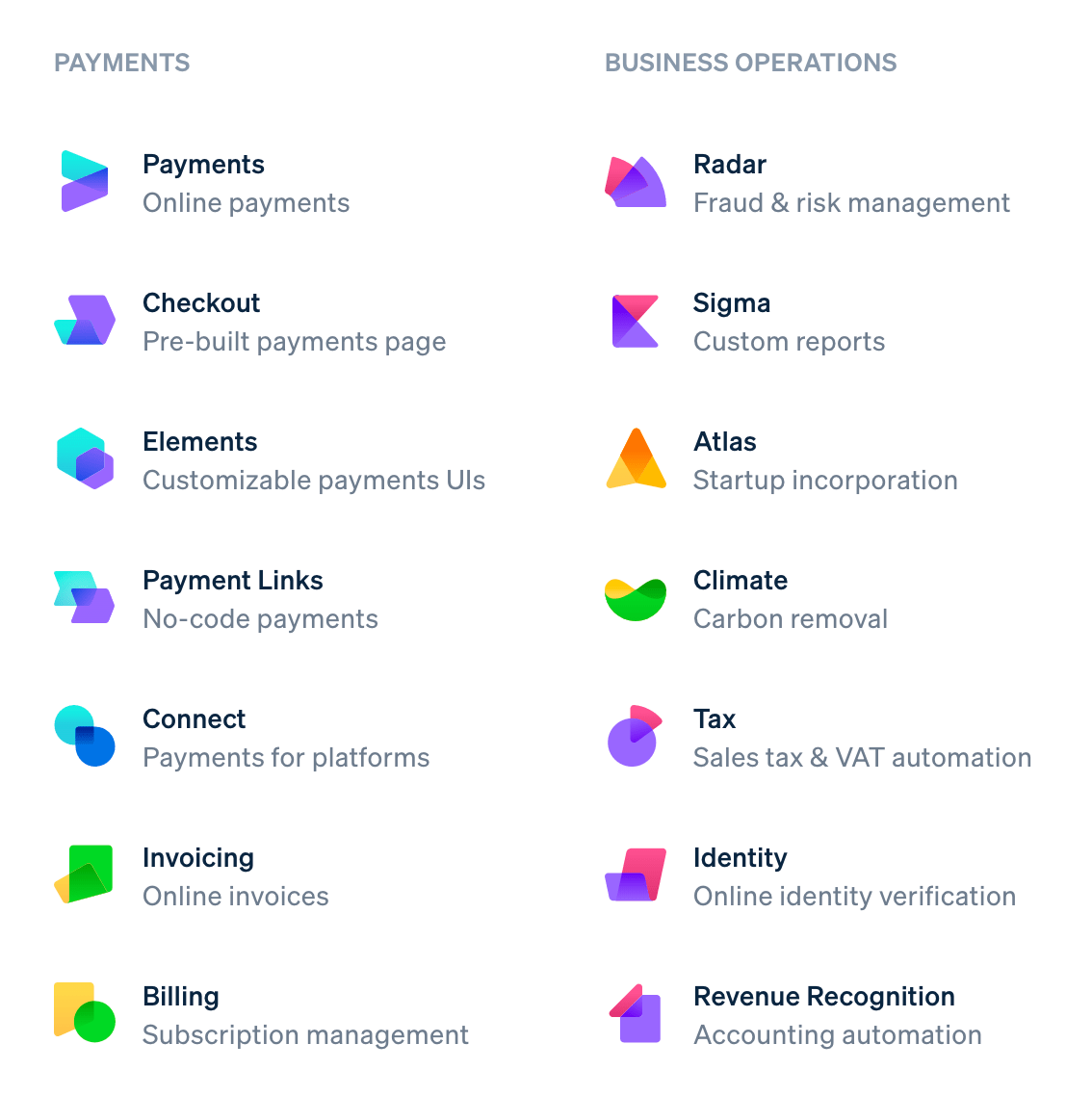

…while Stripe’s more grandiose ambitions have made it grow up fast into a full fintech firm that seeks huge, horizontal scale with minimal customer touchpoint:

These characteristics rub off on their differences in sales approaches too. In contrast to Stripe’s hands-off, horizontal approach to the SMB market (‘no salespeople’ was part of their early philosophy), Adyen follows a traditional enterprise selling playbook where it does its homework upfront and uses targeted presentations to potential merchants.

On the POS business, Adyen’s core large enterprise market is also unlikely to be threatened much by Block. Although Block keeps boasting that it’s increasingly serving large merchants, it defines this market to be anyone who generates over $125,00 in annual sales (which at Worldpay would have been a “small” merchant). Most of its acquisition and investment history give the same clues: Weebly, a website builder, Caviar, a food delivery start-up, Eventbrite, an event marketplace, TIDAL, a music streaming service. All these initiatives are likely to only strengthen Block’s SME ecosystem with little to cater to large enterprises. Its fastest-growing revenue component, Cash App, competing against Venmo, may have overlap with existing merchants but have little resonance trying to go upscale into larger merchants. That said, Block’s Reader SDK offering, which larger merchants use to code their POS application on top of Block’s hardware and payments infrastructure, is what drives Block’s growth with larger merchants that have more customized payment needs. But Block is unlikely to eat away much of Adyen’s potential business unless it looks to also own the entire payment stack. In this line of thinking, Adyen may have more to fear from Fiserv who after the merger with First Data now controls the highly promising POS device Clover which grows ~40% on an installed basis.

Expanding on that thinking, you may even argue that it’s easier for a payment platform to conquer the small and mid-market after having conquered the upper market since you can then offer the merchants best-in-class payment tech and aren’t as easily distracted by other fintechy, grandiose ambitions that may look to expand the payment ecosystem but also keep postponing actual upmarket grab. It’s what Adyen is now trying to do: After having gotten a stronghold of the enterprise market, the company is starting to move down the merchant ladder to the mid-market. The idea is that by offering the same performance and functionality as some of the world’s largest businesses get, merchants with large and international ambitions can carry Adyen along on their ascend and so avoid being hampered by the complexity in business operations that so often comes with growth where you have to bumpily change your entire setup along the way. Adyen’s goal is to get early entry on these mid-market merchants who might grow into global enterprises, entrenching its platform as mission-critical in that journey. To pursue this market, Adyen works at building out education programs and low-touch acquisition and support models (through its partnership with BigCommerce, Adyen promises SME businesses to go live within a day), and by working with businesses like EPOSNow and Lightspeed, Adyen now attempts to unlock its unified commerce solutions for smaller merchants.

Adyen has more times than one mentioned that its take rate does not constitute a driver for the company since the Adyen platform operates at a low cost allowing the company to instead put all its focus on incremental net revenue. This makes sense in the same way that operating margins matter little in light of free cash flows (“Investors can’t spend percentage margins”—Jeff Bezos). But it’s worth mentioning, since it helps understand the business, that there’s an inverse relationship to the number of transactions a merchant pulls through the system and the take rate an acquirer charges. So if the company was to entrench the mid-market at a faster rate than it’s growing with their largest merchants, Adyen’s take rate should move higher from its current 20.6 bps level.

But more important is Adyen’s incremental net revenue growth. Growth in North America stands out, having raised to 22% of net revenue and having grown 80% year-on-year as of H12021. The traction that Adyen enjoys now in the US originates from its geographical advantage. Because Adyen got its start in Amsterdam, it was on the outset focused on the long tail of alternative payment methods in which Europe is abundant (Europe represents 60% of net revenues) after which Stripe, Square, and other aggregators have essentially been playing catchup since then. So when Adyen started out in North America, the company mainly helped US merchants expand outside the region. Now it sells on convenience in unified commerce, taking advantage of the evolving complexity in shopper preferences and payment method proliferation.

The latest evolution in Adyen’s offering is that which caters to enterprise-sized platforms that themselves power tens of thousands of small businesses. Adyen for Platforms, which competes with Stripe Connect, helps marketplaces to distribute payments to sub-merchants and provides the entire payment infrastructure underpinning the platform. In 2018, Adyen initiated a global partnership with eBay. The year after, it partnered with Alipay to facilitate payments outside of mainland China for AliExpress, Taobao, Tmall, and Alibaba.com. And in the same year, it was selected by Uber to be its initial solutions provider for 3D Secure (3DS).

After the eBay deal, eBay cited Adyen’s singular focus on payments—as opposed to competitors’ larger ambitions expanding outside of the realm of payments—as the key reason it selected it as a partner. This is precisely why I think Adyen is in a good position in the increasingly important platform business model. Adyen for Platforms is likely to see significant growth while adding some points to the EBITDA margin on the back of large scale and limited maintenance required in servicing one large platform as opposed to dozens of enterprises. That said, by the same logic that Adyen’s venture into the mid-market is likely to raise take rates, Adyen for Platforms is likely to compress it. What trend will dominate depends on which grows the fastest.

Management targets a mid-twenties and low-thirties net revenue growth CAGR in the medium term and for the EBITDA margin to increase to >65% in the long term while keeping CapEx low at ~5% of revenues. It doesn’t define what “medium-term” and “long term” mean, but if I was to assume that they mean 5 years and 10 years, respectively, I won’t quibble with these targets. They sound reasonable. Adyen will continue to derive significant growth from existing merchants as it grows with them and grows its share of wallet. Wallet share is, for reasons discussed, critical to Adyen’s continued growth story as the company continues to gain dominance in the enterprise market with escalating technology demands. Meanwhile, given Adyen’s massive scale advantage, the EBITDA-margin might move above the 65% level in the mid to long term which is well above legacy peers’ margin in the mid-30 range and which exemplifies the durable cost advantage that Adyen has made for itself by first principles innovation.

The stock is expensive. If you assume 30% annual net revenue growth over the next five years (from which, assuming a constant take rate, Adyen’s processed volume will have grown to >€1.1tln compared to Worldpay’s current $1.7tln), a 64% EBITDA margin in the out-year, no share dilution, and an EV/EBITDA compression from a current eye-popping TTM 142x to a still eye-popping 60x in the out-year, you could expect a ~10% rate of return. While there’s very little room for error in these assumptions, the range of potential growth and profitability of the company is also wide (though these assumptions are at the top of any range I would be comfortable with). Buying the stock at these prices is like buying an option on whether the trajectory will surprise significantly to the upside. Whether it will, I don’t know, but I wouldn’t underestimate the probability of it happening.