You just bought a shiny new bike.

It wasn’t a cheap bike and you ride it around everywhere. You want your new bike to remain as new as possible, and so you take care of it with all your heart. You buy the strongest bike lock that money can buy, and so you lock the bike everywhere you go even as you only park it in theft-safe spots. You even take the seat with you.

One day, you discover that your renter’s insurance not only covers theft and disasters but also your bike. At that immediate moment, you become much more relaxed at the thought of your bike being stolen.

You decide to become a little more careless, and so you stop locking your bike and taking your seat with you every time. Your insurance company knows nothing of your change in behavior.

This is moral hazard.

The Worst Problem of Modernity

I deliberately chose the introductory bike story to be a harmless one. But as we will soon find, moral hazard is a problem that crofts up often in economics and can have significant repercussions when happening at scale and systemically. Nassim Taleb even calls it ‘transfer of fragility’ and the worst problem of modernity.

The basic premise behind moral hazard is that people behave differently if they’re not liable for the full costs or risks of their actions. But the balance of life is that someone will have to pay those costs. In other words, it’s the flip side of being self-reliant—one person decides how much risk to take, and someone else bears the cost if things go badly.

Because it’s such an important topic in economics, contract-making, and policy-making, moral hazard is also a very useful mental model to navigate the world.

In our grand mental models page on Junto, we categorized moral hazard under models in ‘economics and strategy’. But we might as well have categorized the model under ‘systems’ because moral hazard tends to appear depending on the arrangement of the system in which it can thrive. And some systems can even make moral hazard blossom so much that it creates second-order moral hazard effects.

So, to view moral hazard through the lens of systems, let’s now take some examples. Subsequently, we’re going to discuss how one goes about spotting places where moral hazard might crop up. This is a very useful skill to possess and I promise you that your reading will be worthwhile.

Examples of Moral Hazard

I’m going to go through some domains and situations in which moral hazard can or has thrived.

While you read through them, other examples will likely appear in your mind from your life experiences as your mind begins to roll. You might not even have to read the rest of this article. You’ll be able to spot moral hazards everywhere you look.

Moral Hazard in the Insurance System

In line with the bike story, let’s start with the obvious one because moral hazard is an inevitable part of the insurance system. In fact, the name originated from the industry.

Why is moral hazard inevitable in insurance?

The reason lies in how information is distributed in the system.

If an insurer could perfectly observe the actions of the insuree, they could deny coverage to the ones frequently taking risky actions (like not changing the battery in the house’s smoke detector). But since perfect observation is not possible, moral hazard will always be there. It might be mitigated through the use of deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, and the like, but it’s never eradicated.

Note that the term ‘moral hazard’ should not be confused with ‘adverse selection’ which is the case when the insuree decides to withhold information from the insurer. However, some sources distinguish between ex-ante moral hazard and ex-post moral hazard where the latter is described as adverse selection.

The moral hazard that starts off in the insurance system can ignite second-order moral hazard effects in other areas. A patient with private insurance may happily sit through extra tests, and a doctor may happily order them since they know that the patient would not bear the full cost.

Moral Hazard in Venture Capital

Not all venture capital is foolish, but some is. And when it is, it’s usually due to moral hazard.

The reason is that there may be several agency costs inherent in a investor-investee relationship of a startup business. For instance, if cash flows are too uncertain, the entrepreneur may appropriate investments. If effort is not verifiable, the entrepreneur may shirk job responsibilities. And if there are private benefits from continuing a project, the entrepreneur may keep the project going even if it has negative economic value.

The moral hazard problem intensifies as the venture goes through multiple financing rounds and the entrepreneur, having diluted most of their stake, is exposed to little risk. Masayoshi Son, the founder of Softbank and the Vision Fund, experienced this first hand with the fund’s investment in WeWork.

Moral Hazard in Education

Some teachers don’t have it easy—especially at high-end private prep schools.

When a teacher gives a student a lower grade for an assignment that the student might feel they, or the parents, deserve, they might plead hardship. And sometimes that works when other variables come into play—such as if the parents are important benefactors to the school. But by budging to hardship, it’s the teacher that creates moral hazard by rewarding and even encouraging bad study habits.

Moral Hazard in Corporate Governance

Short-termism in financial markets tends to feed into how companies are conducting their business in a principal-agent relationship, i.e. when management has little invested in the company they’re steering or is compensated based on ludicrous measures such as a rising stock price.

Seth Klarman said it best in his 1998 letter to shareholders:

Investors are strangely willing to ignore the moral hazard of their own behavior, rewarding managements which successfully manipulate quarterly earnings into a steady and predictable uptrend.

In other instances, you see the principal in the principal-agent relationship being diluted to such a degree that there’s no principal remaining. Take the example of a listed company of which no shareholder owns more than 1% of the equity. The CEO takes charge, brings their buddies onto the board, starts issuing themselves low-priced stock options, or does a lot of stock unnecessary buybacks while their compensation is directly tied to the stock price.

Moral Hazard in Sales

When a business owner pays a salesperson a fixed salary unrelated to performance or sales numbers, that salesperson is incentivized to put in less effort in doing what they are hired to do. This is, of course, why performance-linked compensation plans are usually used in sales departments.

But with other functions, it may not be as easy a problem to solve. Take consulting services that bill by an hourly rate because no other method apparently works for them. Given the rate structure and the inability of the client to monitor the consultant’s actions, the client would expect the consultant either to bill more hours than the client prefers or to spend time on projects that the consultant values but that the client does not.

Moral Hazard in the Global Financial Crisis

A lot of what happened under the subprime mortgage crisis which ultimately led to the 2007 housing bubble and the Global Financial Crisis can be explained by moral hazard. The entire scene that led up to the crisis was a hot potato in which almost every actor involved in the system pushed risk further down the line.

The mortgage lenders pushed the risk onto investment banks. The investment banks sliced and chopped the loans into complex pools and pushed the risk onto the investors of these mortgage-backed securities. The investors pushed the risk further along through default swaps until the last one holding the risk would be the one facing the largest potential loss: the ordinary taxpayer.

As long as risk could be pushed off, the larger risk the actors allowed themselves to take. It was a moral hazard chain reaction.

Moral Hazard in Geopolitics

The Global Financial Crisis wasn’t the only ‘recent’ crisis that fed on moral hazard. The entire European system discovered that it was subject to moral hazard under the European debt crisis which took place a few years later.

As the Financial Times wrote in 2011:

There are many similarities in the rise of Greece and Lehman. Both were given far too much money far too cheaply by investors, who paid too little attention to the risks they were running. Both used off-balance sheet structures to hide their growing debts. Both had leaders – Mr Fuld and Mr Papandreou’s predecessors – who had every incentive to keep borrowing and ignore the underlying problems.

[…] So what happens if the European Central Bank gets its way, and Greece is rescued again? For investors, that would be good news: the risk of default goes away for a while. The danger is that Greece becomes a sort of global benefit scrounger: addicted to handouts and unwilling to work.

Just like the biggest banks, Greece knows it is too important to fail and it can drag its feet on reform. And it can continue to do so because it’s part of the European system which allows moral hazard to blossom.

How to Spot Moral Hazard

You may have noticed that certain themes keep repeating even as our examples are widely different.

Here’s what we can deduct: moral hazard must be seen in connection with principal-agent relationships, information asymmetry, and incentives.

These are all other mental models and they usually work in the same direction when moral hazard occurs.

The first condition behind moral hazard is that there’s a contractual obligation that binds two different agents and affects their behavior. Moral hazard can occur at any time two parties enter into a contract with one another and each party in the contract may have the opportunity to gain from acting contrary to the principles laid out by the agreement.

It doesn’t have to be a principal-agent relationship like our examples above in venture capital, corporate governance, and sales. But there’s a greater risk of moral hazard to occur whenever one agent is able to take actions on behalf of the other agent (which makes them the principal).

The reason lies in the second condition.

The second condition behind moral hazard is that there’s information asymmetry in which one of the parties holds more information than another.

Remember how this is why moral hazard will always be present in the insurance system? An insurer will never get to the same level of information as the insuree, and so moral hazard is always lurking.

But it’s not always so straightforward. It depends on the level of immorality inherent in the decision. With insurance, rarely do you find an insuree who finds it flat-out immoral to be less prudent about their possessions if they’re protected by insurance. The level of immorality is low—at least in the eyes of the agent.

You would therefore think that the level of immorality would affect the degree of moral hazard taking place in the system so that a minor level of immorality would result in more moral hazard. It might be so in some domains, it just wasn’t so within the investment banking departments leading up to the Global Financial Crisis which largely fed on information asymmetry.

A firm selling sub-prime loans may know that the people taking out the loans are liable to default. However, that firm may continue writing these bad loans as long as the bank purchasing the mortgage pool has less information and assumes that the mortgage is good to go. Here, the level of immorality is right at the top.

Information asymmetry also works if you think in terms of ‘personal distance’. The closer the agent is to the one bearing the risk, the less likely that agent is to conduct moral hazard. In our two examples above, there was wide personal distance between the agent and the one ultimate risk-holder. The insuree knew little of the insurance company covering the risk, and the mortgage lender knew little of the investor that ultimately took the loan on their books after it’s been bundled together with a bunch of other loans.

But let’s think about the patient with private insurance again. In this example, a doctor may feel no regret in putting the patient through extra tests when the majority of the bill is covered by an unbeknownst insurance company. But if the doctor knew that the patient was uninsured, they might be more reluctant to take advantage of the situation as the personal distance to the one bearing the risk is now much narrower.

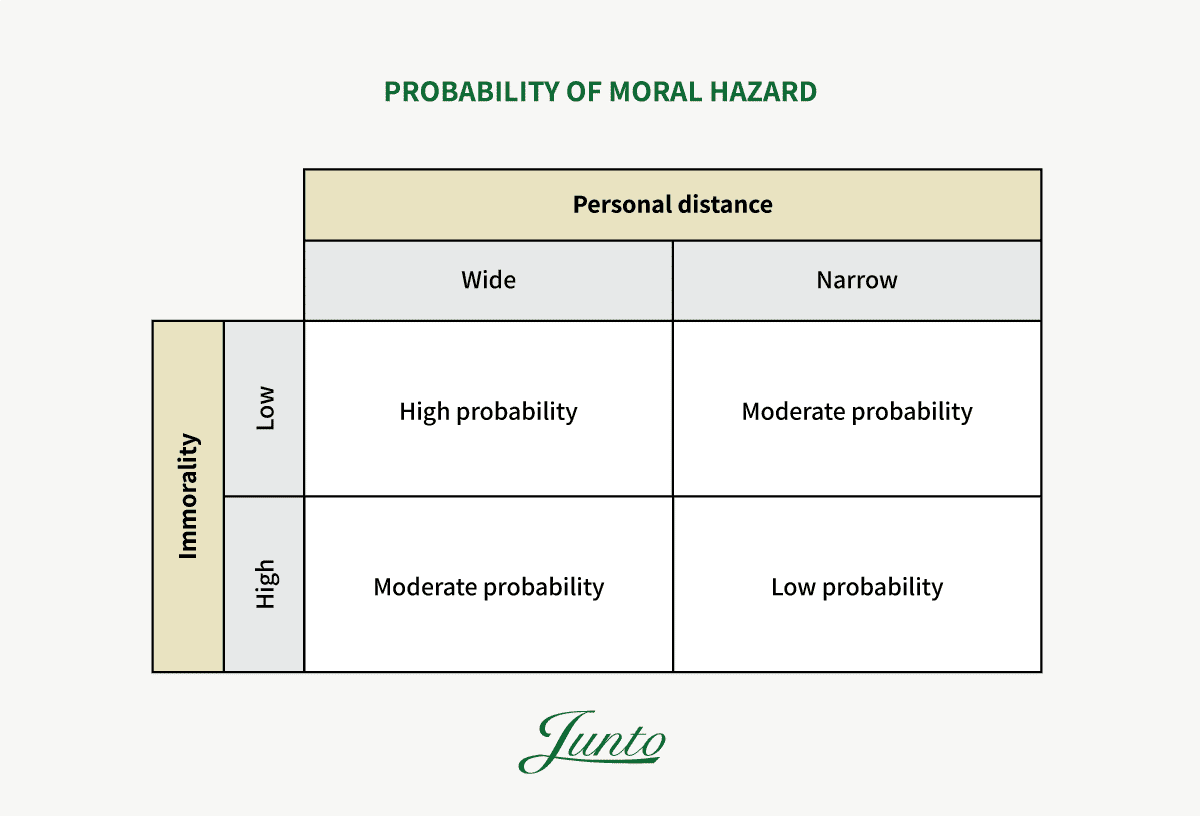

We can thus construct the following matrix:

A contractual agreement between two agents has the highest probability of leading to moral hazard if that the immorality of one of the agent’s actions is low while the personal distance between the agents is wide. This is, again, why you most often see this behavior in insurance.

The third condition you have to look for is the incentive system inherent in the thing you are looking at. Incentives are what bind the other conditions together to create a lollapalooza effect of moral hazard.

This is another reason why moral hazards more often occur in principal-agent relationships as opposed to agent-agent relationships. The principal’s incentives are often different than the agent’s incentives. This invites moral hazard.

Thus, if there are carrots, there must be sticks. In Nassim Taleb’s words, it means there must be skin in the game. To avoid moral hazard, nobody should be in a position to have the upside without sharing the downside.

***

So, this is how you spot moral hazard. You look for the three conditions.

Now, does it mean that moral hazard will always occur if our mentioned conditions are there? No. There’s one powerful mental model which might get in the way of that.

Which is trust.

Trust produces increased speed, efficiency, empowers ethical decision making, and hence, decreases costs.

It’s why Berkshire Hathaway’s system works so well because it’s built on a seamless web of deserved trust in which long contracts are rarely necessary.

Charlie Munger explains:

The highest form which civilization can reach is a seamless web of deserved trust. Not much procedure, just totally reliable people correctly trusting one another. That’s the way an operating room works at the Mayo Clinic.

If a bunch of lawyers were to introduce a lot of process, the patients would all die. So never forget when you’re a lawyer that you may be rewarded for selling this stuff but you don’t have to buy it. In your own life what you want is a seamless web of deserved trust. And if your proposed marriage contract has 47 pages, my suggestion is do not enter.

Note the word ‘deserved’. Deserved trust is built on years of good behavior transformed into a good reputation. Trust can override all three conditions leading to moral hazard if it’s strong enough. It’s a powerful force.

However, when you put information asymmetry and perverse incentives into the picture, trust is also a fragile thing. The teacher would only have to change the angry student’s grade a single time for trust in the system to cease and moral hazard to take over.