Investment Applications of Operant Conditioning

Here’s how you can apply B.F. Skinner’s work to understanding market behavior and yourself.

I want to introduce you to a framework.

It’s the overarching framework that I use for making important decisions, whether it’s specific investments or life decisions.

Now, you might ask why I decided to write a long guide like this about something as simple as making decisions.

That’s an easy question that requires a bit of a longer explanation.

Making decisions determines the trajectory of life. In other words, where we end up is a function of the decisions we make. And thus, developing good decision-making abilities is central to achieving the right goals, keeping or discarding the right relationships, and living the life we want. In the same way compounding interest increases wealth, good decisions produce exponentially better results the more of them we make. So learning to make them well is a very healthy investment.

Well, of course, luck is involved in every outcome of our decisions as well. And the role of luck, as well as the narrative fallacy, has to be respected. I mean, the ovarian lottery is obviously a very important factor in how we end up and what we can make out of the cards we’re dealt. Just as the saying goes:

Luck is what you’re dealt, fate is how you play your cards.

Some people are simply born with a pair of aces. But the sad thing is that some never realize it and they go through life thinking that everything they have is a direct product of their own behavior. This might be true, and it might not. But it’s irrational to think that it’s 100% true. A great book on this subject is The Outliers, by Malcolm Gladwell.

Now, there’s also a saying that goes:

The key to success is playing the hand you were dealt like it was the hand you wanted.

What this means is that a wise player can play a weak hand and still win the game. But only by making rational decisions one after another.

And that’s what we’re getting at: The ability to make rational decisions.

Rational, as opposed to perfect, is the right word here because a decision should not be judged solely on its outcome. For every decision, there’s only one outcome, no matter if that outcome is unlikely. This is Nassim Taleb’s main argument in his book, Fooled by Randomness, in which he talks about alternative histories. These alternative histories are other things that could have happened just as easily as the ‘visible histories’ that did. Understanding this gives an enormous advantage in life. Improving decision quality is about increasing our chances of good outcomes, not guaranteeing them.

And thus, a rational decision is one that a logical, intelligent, and informed person would have made under the circumstances as they appeared at the time before the outcome was known.

Great decisions don’t happen by accident. But we must recognize that there are all kinds of them.

There are three dimensions to just about every decision.

Dimension 1: Skill and Luck

We’ve already established that there are essentially two things that determine how our lives turn out: the quality of our decisions and luck. Elements of both exist in virtually every outcome.

Because this is true, it is also true that the role of luck varies for each of these outcomes. It, therefore, makes sense to think of every activity on which a decision will be made upon as existing somewhere on the continuum between skill and luck.

One person who has done a lot of thinking and writing on the role of luck is Michael Mauboussin. In his book, The Success Equation, he writes:

There’s a quick and easy way to test whether an activity involves skill: ask whether you can lose on purpose. In games of skill, it’s clear that you can lose intentionally, but when playing roulette or the lottery you can’t lose on purpose.

With the game of roulette, we know all the potential future states and the probability distribution. We know that it’s always a losing game because the house takes a cut and because of the numbers 0 and 00. You can’t be a professional roulette player and you can’t make rational decisions when playing that game; Every decision to put money on a roulette table is irrational. Thinking otherwise is subject to gambler’s fallacy and a bunch of other psychological errors. Nonetheless, some people do decide to occasionally walk down to a casino’s roulette table and gamble with their life savings.

Here comes the next problem: The world is not arranged like a game of roulette.

The probability distribution of outcomes in the real world is rarely known. Today, of course, humans strive to know as much as is humanly and technologically possible, deploying such modern techniques as derivatives, scenario planning, business forecasting, and real options. But as is described through the likes of chaos theory, even centuries’ worth of mathematical discoveries built on giants such as Bernoulli, Gauss, and Pascal can do only so much. As novelist G.K. Chesterton wrote:

Life is a trap for logicians.. It’s wildness lies in wait.

In investing, the skill vs. luck continuum depends on the style of investing involved and the business environment at the time which is always changing. It’s very interesting because in investing it’s hard to beat an index but it’s also hard to underperform it, especially if you are diversified and minimize trading fees. 50% of all stock market participants will end up in the bottom half and 70% will end up in the bottom 70%.

But because the game of the stock market is further to the skill-end of the continuum, some shrewd people will have an advantage. And because the amount the house takes (i.e. brokers and market makers) is so much lower than pretty much any other market, these shrew people get better than average results in stock picking.

Dimension 2: Knowns and Unknowns

Uncertainty, not risk, is the difficulty regularly before us. That is, we can identify the states of the world, but not their probabilities. There is no way that one can sensibly assign probabilities to the unknown states of the world.

Richard Zeckhauser

Knowing what you can know and knowing what you can’t are both vital ingredients of deciding well. The very best investors are certain of just about nothing. It sounds like complacency, but it’s an important truism. Good decision-makers are content with the world being an uncertain and unpredictable place. And so they try to think probabilistically. Instead of focusing on being sure, they try to figure out how unsure they are.

If you for any decision are able to approximate the skill vs. luck continuum for the problem at hand, you will make better decisions than those who think improperly about those issues or who don’t think about them at all. You will gain an enormous advantage over them. But if your decision-making skills are not appropriate for the problem at hand, it doesn’t help much.

When one doesn’t know of the potential future states of the world, Richard Zeckhauser refers to that as ignorance. So, the best we can do is try to rationally approximate the correct probability distribution and shape by thinking deeply about the problem at hand. In doing so, we can go from full uncertainty to instead knowing and controlling risk, thus escaping Zeckhauser’s state of ignorance. But we’re almost certain to include some amount of ignorance because we can only identify the states of the world, but not their exact probabilities.

When dealing with future states of the world, it’s almost like trying to win the loser’s game where we all must play like amateurs play tennis; The one who gains the competitive advantage is the one that is less likely to miss getting the ball over the net. Just being consistent and conservative can help the lesser player win a match against a formidable foe with a reckless game plan.

This is why the circle of competence is a very important mental model. The best and easiest way to lower a failure rate is to avoid investing in situations that you don’t understand or don’t have experience with. The goal of an investor who follows a circle of competence approach should be to consistently avoid stupidity.

Dimension 3: Importance and Unimportance

The third dimension of how decisions can vary is in terms of importance. Many types of decisions exist and we make many of them every day—perhaps a couple of hundred of them each day. But many of them are unimportant and don’t matter.

Decisions like where to buy your coffee or what brand of a white shirt to buy are examples of the unimportant. This is not what we focus on here and these are not what the framework I’m about to introduce is intended for. It would not be possible to get out of bed in the morning if every human decision had to be made based on careful expected value calculations.

Looking at the decision you’re about to make and deciding how important it is or whether it’s important at all is a rational thing to do. It’s really a Russian doll kind of thing to think about how you think about problems. But it’s very important.

Equally important is it to weigh decisions against one another and have a hard look at setting the right priorities for how your few waking hours are spent. Every decision commits us to some course of action that, by definition, eliminates acting on other alternatives. Not deciding on something is, in itself, a decision. It’s therefore important to make small decisions into routines and sleep on the big ones.

For example, some people spend more time researching their next car than checking out their investment options in their retirement plans. Not to mention trying to understand the investments they make themselves. And some people spend days finding just the right refrigerator but are willing to put half their life savings into a stock tip they heard from a friend.

These examples are very irrational. This leads us to the next section.

Before getting to what makes for a rational decision, I find it important to first invert the issue and think about what gets people to make boneheaded decisions. These are the complete opposites of rational decisions.

All I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I’ll never go there.

Charlie Munger

For a starter, the pitfall of gambling in casinos is a given boneheaded decision. Addicted gamblers are influenced by a bunch of factors that feed their addiction. Some of these are the gambler’s fallacy, envy, culture, and social proof.

But there are other examples of boneheaded decisions which are a bit more complicated:

History is awash with irrational decisions. And the common theme behind each of them is that they have been driven by either cognitive biases, using wrong information, using ill-represented models of the situation, or doing what’s easy rather than doing what’s right.

I also want to include here another issue which is usually a bad decision and is one of the main reasons why hedge funds and great investors are as secretive as they are about their investments. That is publicly writing about your investment ideas.

The reason why it’s usually a bad idea has nothing to do with coattail riding or front running. It has to do with human psychology. This argument is best understood through a very interesting story about Chinese Communism during the Korean War which is described in Robert Cialdini’s brilliant book, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion:

During the Korean War, Chinese Communists used what they termed a “lenient policy” in order to get captured American soldiers to collaborate with their wishes. While the North Koreans favored harsh punishment for this goal, the Red Chinese opted for a sophisticated psychological assault. This tactic turned out very effective in getting the Americans to tell on one another and nearly all American soldiers captured by the Chinese during the war are said to have collaborated with the enemy in one way or another.

The way the Chinese managed to do that is rather interesting. They knew that in order to get any collaboration at all from the Americans who were heavily trained, they needed to start small and build.

They began by asking the captured to make mild statements such as “The United States is not perfect” and “In a Communist country, unemployment is not a problem.” And once they complied, the requests became bigger. When an American soldier had just agreed that the United States is not perfect, he would be encouraged to expand on that statement. Later, they might ask him to read his list of arguments to the prisoners. Still later, The Chinese might use his name and essay in an anti-American broadcast sent to the camp, other camps in North Korea, and to American forces in South Korea. Suddenly, the soldier would find himself a ‘collaborator’, having given aid to the enemy by initially making a small commitment.

Publicly writing about investment ideas and holdings invites this very commitment bias. If one tells all kinds of great things about a specific investment, a change in circumstances may suddenly occur, or a change to the analysis may be made. Companies are breathing entities that are going through changes every day. But because the human mind has a tendency to commit to what is self-publicized, it causes a distortion in thinking, and it might hinder a necessary change in perception when the facts change.

Yes, I know what you’re thinking. You’re right. this is exactly what I do here at Junto. How crazy am I?

Based on what we’ve established thus far, what does the anatomy of a rational decision look like?

We can fairly conclude that it lives up to the following:

Sometimes, this leads to hard decisions where less rational, but much easier, decisions could be chosen. But here, it’s important to recognize that hard, but correct, decisions made well today prepare us to make decisions more easily tomorrow.

It all seems rather simple. And it is. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Making rational decisions takes a lot of practice, hard work, and discipline. Especially when those decisions require a contrarian view.

Because as we have already established, whether it’s investing or life decisions, it’s impossible to have perfect and complete information for all variables involved with dealing with the world. And therefore, it’s also often impossible to understand the important phenomena that are affecting circumstances today from the perspective of any single incomplete system of thought. The cure is to gain a wide interest and curiosity for the world from all perspectives and fields such as philosophy, economics, psychology, mathematics, physics, biology, and history in order to make greater decisions no matter the problem at hand.

Although this accomplished and crucial fact is quite commonly recognized, it, unfortunately, is not as widely practiced, especially in the financial industry. Disciplines develop their internal ways of looking at the phenomena that interest them, and when an entire field operates in such a state, it quickly allows for dangerous behavior such as herding, reinforcement of preconceptions, consensus-seeking, incentive-caused bias, and suppression of critical thinking. It leads to the man-with-a-hammer syndrome where every problem looks like a nail.

That is why I’ve thought long and hard about a framework that aims to keep rational decision-making in check and which allows us to keep emotions from corroding that framework.

The result of that is the following.

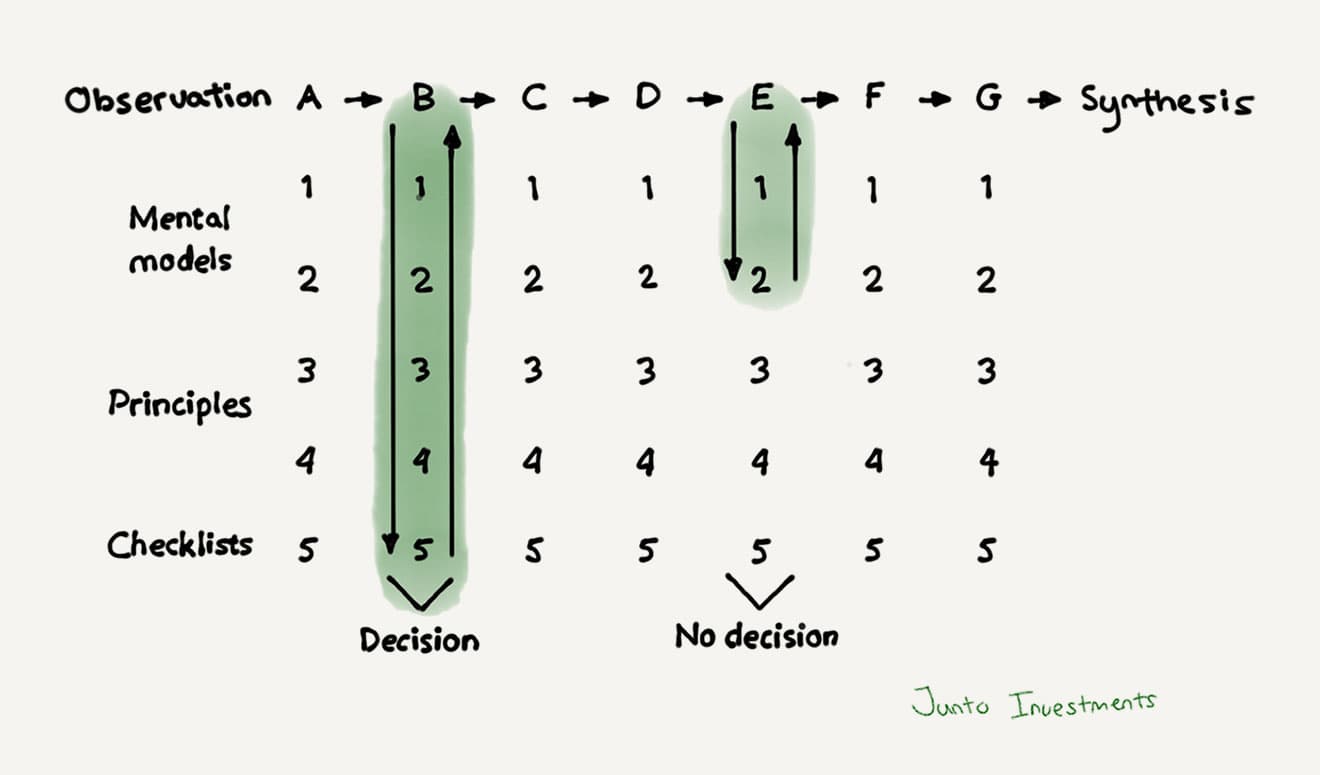

Now we’ve arrived at introducing the Decision Levels framework that overarches every important decision I make. Here it is:

I will let the explanation of the framework be guided by how I approach investment decisions since that is the central purpose at Junto.

Observation

One cannot make great decisions without being a great observer.

The top-level is where I collect pieces and study broadly using a wide reading spectrum of annual reports and SEC filings, industry reports, trade journals, newspapers and other periodicals, books, etc. These studies are random because it’s a game of filtering noise from the signal. Studying hundreds of businesses upon businesses helps me know when something wonderful hits my way.

Mental Models

One cannot efficiently apply multidisciplinary thinking without using the right models.

When an interesting topic is identified at the observation level, I look at how the subject fits into reality through the use of mental models from multiple disciplines. They shape the connections and opportunities that I see. Examples of the most important models in every investment decision include the circle of competence and opportunity costs. But there are lots more.

Principles

One cannot know their moral compass or the road to the end goal without setting the right principles.

Next, I investigate how the subject or idea fits in terms of my principles. These principles act as the operating system for decision making. Because while mental models help with comprehension, principles guide behavior. These are simply imperative. Here are some of my principles for business, life, and learning.

Checklists

Checklists establish a higher level of baseline performance.

Lastly, if the topic reaches the bottom level, my checklist for the topic at hand is carried out. I have different checklists and criteria for different types of decisions and for different aspects around the subject, including bias reduction, risk of the subject, competition, financial shenanigans, etc. Checklists remind me of the minimum necessary steps in coming to a rational decision and they make them explicit. They not only offer the possibility of verification but also instill a kind of discipline of higher performance.

Of course, this framework is more of a thought process. But recognizing that thought process through the use of an overarching framework sometimes turns out to be mighty powerful. So rather than being a hard template, the Decision Levels framework acts as a mental model in itself in which you want to gain fluency in order to think better and decide at your optimal state.

Hence, just as decisions vary in dimensions and facts change, think not of the Decision Levels framework as something rigid. Think of it as a filter to connect information in order to arrive at decisions for solving important problems where each step in the decision-making process takes place at a deeper level and all the most important decisions are taken at the deepest level.

Remember that decisions need to be made at the appropriate level, but they should also be consistent across levels.

The groundwork is now laid out. Time to dig deeper.

This is a complete list of articles I have written on the subject.

Here’s how you can apply B.F. Skinner’s work to understanding market behavior and yourself.

Being a serious student of the markets is a must for investing success. But the nature of the markets is only part of the intelligent investor’s syllabus. What’s even more important is the lesson of knowing thyself.

Marketers use anchoring to trick you to spend more money, negotiators use anchoring to get in the stronger position, stock investors fall prey to anchoring to their own detriment.

How to use the timeless tool of a checklist to reduce the rate of error in important decisions.

While mental models guide comprehension, principles guide behavior.

My story, motivation, and how I came to the position of starting this peculiar endeavor.

Know the kind of game you’re playing before you start playing it.

Moral hazard is present in more domains than you think. Learn the useful skill in life of spotting moral hazard by using these three mental models.

When you’ve got something good, it’s working, and you’ve spent a lot of energy getting there, it’s probably best to sit on your ass and enjoy the ride.

Entrepreneurs want their business to be lasting and fulfilling. The key is in doing deliberate work.

© 2023 Junto Investments, all rights reserved. The content provided on the Junto Investments (“Junto”) website is for informational purposes only, and investors should not construe any such information or other content as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained on junto.investments constitute a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer by Junto or any third party service provider to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments in this or in any other jurisdiction in which such solicitation or offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. See our Terms, Privacy Policy, and Disclaimer.