In bear markets, stocks return to their rightful owners.

John Pierpont Morgan

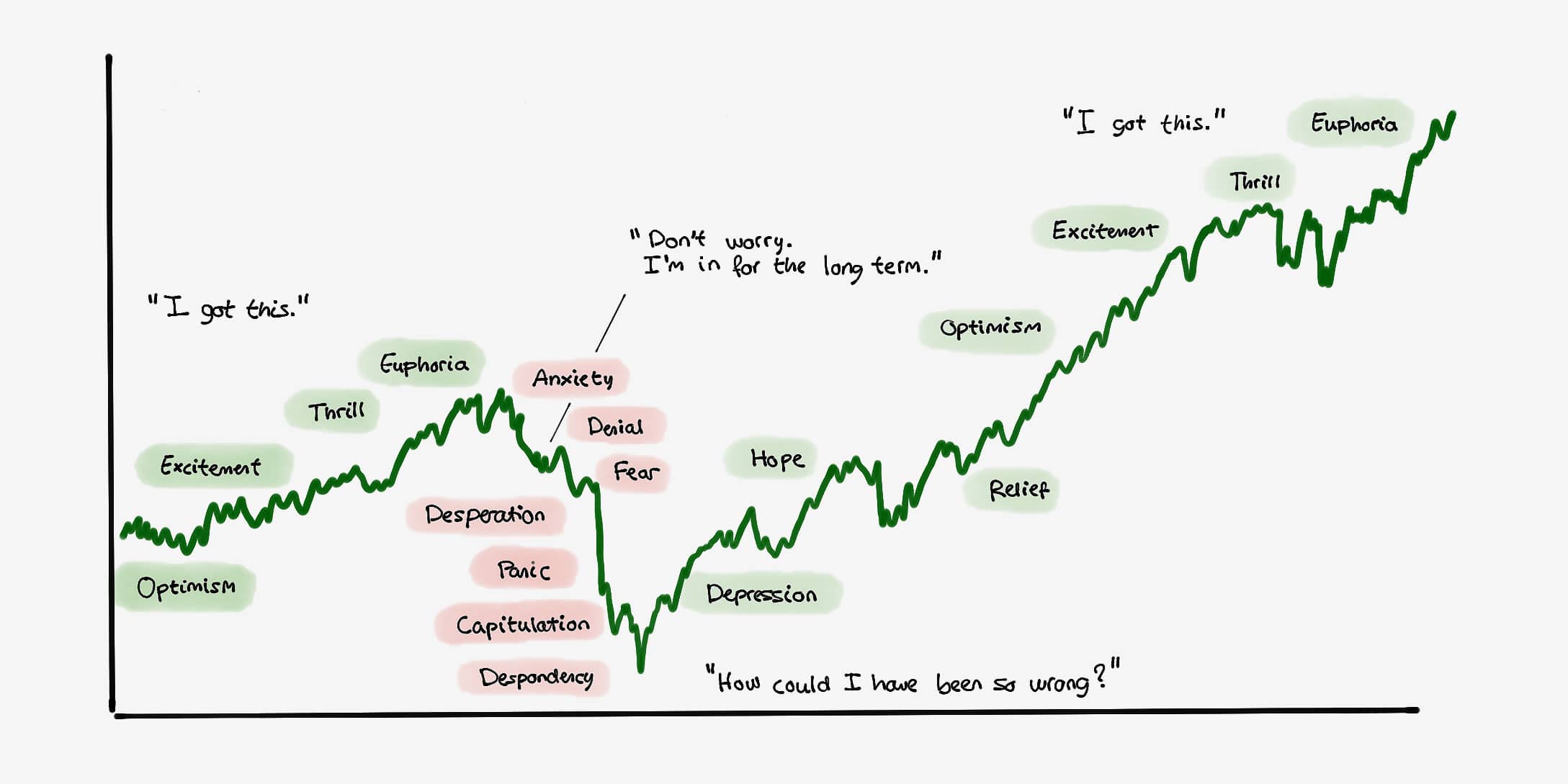

In times of panic and sell-offs, it’s tough to tune out the sentiment, the media (mass and social), and a bunch of potentially worthless advice from financial advisers, strangers, friends, and family.

The problem of human nature is our urge to control and forecast uncertain events and we desperately turn to people whose best guess is not any better.

We can’t stand the fact that we are not able to control the direction and size of the tide. But the tide is there to lift or sink all boats. Sometimes that leads to overvalued assets and sometimes that leads to bargains on sale.

Of course, if one is unable to identify such, it doesn’t help much. As Charlie Munger said at the 2020 Daily Journal Annual Meeting: Let me know what your problem is and I’ll try to make it more difficult for you.

I’m not going to go into the repercussions of the current coronavirus outbreak, the oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, nor the fact that the U.S 10-year bond rate has gone from 1.88% to a low of 0.40% since the start of 2020. Of course, this is uncharted territory with no clear outlook of the result or duration.

The fact is, the world is in uncharted territory all the time. The financial crisis caused by dangerous inventions of derivate instruments was uncharted territory. The two world wars and the Cuban Missile Crisis were uncharted territory. Our current interest rate environment and political climate is rather uncharted territory.

Just over the past 30 years (which is a short period), the scaremongering of world events has not been spared. Since 1990, the world has faced four global recessions, the first and second Iraq wars plus Afghanistan, 9/11, a bond market crisis which nearly took down the global financial system by the fall of Long-Term Capital Management, a crisis almost as fierce as the Great Depression, the downgrading of U.S. Treasuries (a risk-free asset), the U.S savings and loan crisis, trade war, not to mention outbreaks of swine flu, SARS, Ebola, and Zika viruses.

What’s interesting is that over that same period, the S&P 500 index has returned 1,626% with dividends reinvested from January 1990 to the end of December 2019, while world equity markets collectively have returned about 710% looking at the All Country World index.

The hindsight bias is strong. But that is probably the fortunate thing about the future being unknown. If equity investors had a crystal ball to foresee these events, a lot would undoubtedly not have participated in the markets for the last 30 years.

And of course, this only provides a clue and really says little about how the future will look from current circumstances. Each dangerous event has caused very different depths of crashes and subsequent rebounds. And the only thing we pretty much can predict with certainty is that we’re going to go through many more things that will test people’s temperament in the next 30 years.

Buffett’s 2008 Message to Investors

During the darkest hours of the financial crisis on October 16th, 2008, Warren Buffett published an op-ed in the New York Times titled Buy American. I Am.

As you might have noticed by the date, the piece was written and released very early from the stock market bottom which happened in March 2009 and only about a month after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy. So at the time, the op-ed was released, the market was rather far from bottoming. The S&P 500 had another 26% to fall over the course of the next 5 months after Buffett publicly stated his intention to buy aggressively into the panic. And buying was a wise decision.

Ultimately, his message was that the long-term outlook for the U.S. economy was still intact and the crisis made stocks cheaper. The timing, and how cheap they would eventually become, didn’t really matter. The fact that Buffett’s timing was off from the market is why that op-ed is such a good lesson.

The thing to learn about times like these is that investing is a temperamental game rather than an intellectual game. It’s about staying rational and knowing what’s predictable and what isn’t. Investors are better off looking at their individual businesses rather than obsessing at what the market might do next. Because…

Nobody Knows

In Howard Marks’s recent memo at Oaktree Capital titled Nobody Knows II, he said:

Will stocks decline in the coming days, weeks and months? This is the wrong question to ask… primarily because it is entirely unanswerable […] Instead, intelligent investing has to be based — as always — on the relationship between price and value.

Hence, when asking others for advice on when to buy and how long the current situation will continue, beware: No one else has any idea, even if they say they have some idea, and especially when they say they have some idea.

And about the Coronavirus outbreak, Howard Marks underlined the fact that one should focus on the fundamental effect on life and business:

So, especially after we’ve learned more about the coronavirus and developed a vaccine, it seems to me that it is unlikely to fundamentally and permanently change life as we know it, make the world of the future unrecognizable, and decimate business or make valuing it impossible.

Of course, markets are bothered about the economic disruption that ripples across supply chains, the pressure it puts on health care systems, and the shifts it causes in supply and demand for raw materials. No sector seems immune.

Here, it’s important to remember what lies behind value, which is the amount of cash an investment can throw off each year into perpetuity discounted back at an appropriate rate. This means that what happens in the short-term (in terms of years) matters much less than people tend to weigh. The vast majority of an asset’s value lies in what happens beyond year 3 – that is the perpetuity, after all.

What Howard Marks is saying is that as long as the outbreak is unlikely to make the future unrecognizable and make valuing businesses impossible, investors, who can expect to know the value of their businesses in an eventual regular environment, should know how to react in the current environment.

This brings us to the road to equanimity and the answer to the question everyone asks: “Should I buy or sell?”

The truth is a lot of people will not like the answer because it doesn’t help very much in terms of being subject to the market’s current volatility. Let me know what your problem is and I’ll try to make it more difficult for you.

Buy stocks if you expect long-term cash flows of the given company and its intrinsic value to improve considerably over time. Sell if you expect the long-term cash flows of your businesses to deteriorate over time. Wait only if you lack clarity now. In investing, well-thought inaction is often the best route. Instead of asking Mr. Market for advice, look for what opportunities he provides.

Ending remark: If you think things are looking bad, remember you today are as rich as John D. Rockefeller in 1916. Richer, actually.