Pricing Power

A complete guide to pricing power and how to identify it in its most durable form.

In this guide, I’ll cover:

“We have found in a long life that one competitor is frequently enough to ruin a business.”

—Charlie Munger

One irrational mistake many investors make is buying a stock based on what the company has done in the past even if that doesn’t translate into any conviction for how the company may thrive in the future. The truism of stock investing is that you don’t buy a company’s past cash flows. You buy the future. But what a lot of investors incautiously do is they buy widely popular companies that have shown immense promise in recent years in perhaps an exciting new industry only to discover that such companies may fail to live up to the expectations set for the next 10-20 years, especially taking into account the price paid for the stock.

The “exciting new industry” part is noteworthy since the two-folded irrational mistake is trying to pick the right industry by assessing how much it’s going to affect society or how much it’ll grow. To the untrained in second-order thinking, there is one primary reason why that approach is bound to disappoint in one’s investment performance.

There are some industries, and often that’s the new and exciting ones, that have little to no barriers to entry. The name of the game in such industries is that you need to run faster than the others. And, of course, that’s exciting stuff because that’s where you’ll see the most innovation coming in with the prospect of immense shareholder value creation. But this is often an utter illusion. Having to run fast is a long-term setup for failure. You’ll always have competitors who are looking at what you’re doing, trying to figure out your weaknesses, and waiting for the right moment to attack. Fat earnings are an invitation for others to come in and sample the cream. History is awash with examples of companies experiencing rapid growth that ultimately burn through shareholder’s capital. The reason for this is simple: if supply outpaces demand and companies don’t possess an economic moat, it doesn’t matter how fast demand grows—everyone except maybe the customer loses. Examples include railways in the Victorian era, automobiles in the 1920s, fiber-optic cable in the late 1990s, wireless networks in the 2010s (specifically in regards to new network upgrades that weren’t yet monetized), solar panels in the early 2010s, shale oil and gas in the 2010s, and more recently, cannabis and lithium. You might even want to throw some recent pockets of SaaS in there. Typically, stocks rise as investors anticipate a surge in demand only to fall later on when supply exceeds demand and losses accumulate. Industry is not destiny.

So the key to investing is not assessing how much an industry will grow but how its economics are divided between the players who possess durable competitive advantages that allow them to squeeze and forward the value to the shareholders. A company that has grown earnings recently but doesn’t give any clues as to whether they’ll grow consistently doesn’t have that ability, and buying the stock for those unknown earnings does little for you. A business like that may be well-run with great management that always does the right thing when their backs are against the wall, and they may even possess a unique advantage that differentiates it from competitors to generate attractive profits, but since there’s no assurance that such an advantage will yield long-term protection of earnings power, it isn’t durable and thus holds little value to the investor. Short-term advantages are useful, but they shouldn’t be mistaken for moat-building.

As Michael Porter has said:

“It’s incredibly arrogant for a company to believe that it can deliver the same sort of product that its rivals do and actually do better for very long.”

And this is where you find the key differentiator between an economic moat and a competitive advantage: an economic moat originates from competitive advantages (the more, the merrier), but for those advantages to merge into a moat, they have to be sustainable.

Of course, all of this matters little to short-term traders or short-term investors. The marginal buyer of a stock that aims to only hold it for a couple of months will, of course, not place much emphasis on the company’s moat, because the advantages that make up the moat won’t matter much over those couple of months. What matter over that period are market sentiment, news flow, and short-term momentum. The reality is that this is the field the majority of the investment industry plays in.

Consequently, due to short-term temperament being an inherent trait of the stock market, there’s always room for immense value creation in competitive advantages that last for years and years. In other words, companies with moats that are truly durable almost always trade too cheap. The reason why is that the vast majority of the company’s present value lies in the outer years.

Now, if you’re an investment banker doing valuations for a living, what do you do? You’re valuing one company after another and all you really do is project into infinity for every company that comes across your desk. That’s bullshit and everyone knows it. The investment banker knows it. For the vast majority of valuations, the terminal is just a tie-up to the model. The valuation that assumes a cut-off to the terminal period is few and far between but the truth is that that’s the reality of the business ecosystem. No company lasts forever. Some last a few years, some even for a few months, and some last for centuries. Some last for decades without creating any value. Only rare companies create value long enough for the present value difference between ‘really long’ and ‘infinite’ to become insignificant.

If you really, truly think about it, how many companies can you feel comfortable projecting five years into the future, then another five years, then another five years, all the way into infinity, with even close to what is real conviction? And on top of that, how do you know that the prospects you’re projecting will all be value-accretive to shareholders? It’s simply not possible. For valuations with little conviction, the terminal means nothing—perhaps from a learning perspective but not to make a qualified investment decision.

To the serious analyst, what’s the remedy? Well, first, the remedy is to study a lot of businesses—over a lifetime—and then if you’re lucky, you’ll find a handful of real moats that you can confidently project with overwhelming odds. Studying company after company is what gives you predictability, and predictability is a must. The basis of that predictability is a wide moat around the business that protects it.

When thinking about moats and entry barriers, it’s very easy to get symptoms and causes mixed up. We usually think of moats as something concrete to slap on a description of their origin. “This company has a moat because it’s capital-light and retains >90% of customers per annum.” A lot of such descriptions are symptoms, not causes. It’s like Richard Feynman’s saying:

“I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something”.

—Richard Feynman

Mixing up symptoms and causes has another consequence which is that you may run the risk of dismissing moats in places where you don’t expect to find them, or, contrastingly, discover moats where you do expect to find them but that are elusive or aren’t as wide and deep as you think. Southwest Airlines is an example of a company that operates in a notoriously terrible industry burdened with gigantic fixed costs, a commodity product that earns its margins on the tail end, huge debt, and big price wars with imminent bankruptcies to follow. But with Southwest, the context of these terrible industry economics is the actual source of their moat-building at the expense of bloated/lazy competitors and at the benefit of the price-conscious customers. Southwest’s cost discipline, plane agility, and standardized fleet are what continuously flow into the key differentiator for a commodity product such as plane tickets: low ticket prices. What’s important to realize is that it’s all the little intricacies and nuances that make Southwest’s unreplicable ‘low-cost operator’ model work. This isn’t much different from the scale economies shared you see at some of the most successful retailers like Walmart.

What this means is that it’s often a waste of time to analyze a company’s current products and market when you want to assess its future value. When Amazon listed in the late 90s, even the most bullish analysts thought that the TAM was $26bln which equated to the total book market in the US. What they failed to appreciate was that Amazon’s extremely adaptive, long-term culture stampeded every factor you could have included in your 90s analysis of the company. That’s the most important ingredient in moat-building: a culture that’s willing to invest for the long term and management that is unsympathetic to playing the quarterly circus of Wall Street.

Moats aren’t built out of thin air; they’re built by humans. And so what’s usually left behind in the moat discussion is the aspect of incremental daily improvements that aren’t noticeable in the everyday financials but which slowly turn into formidable protection of the castle. A culture that’s fanatical about the little daily improvements is the intangible glue that can hold fast-growing businesses together, the facilitator that gives space for innovation, and the sole reason why companies can emerge stronger from adversity. All the way to the micro level, if the company is continuously delighting its customers and eliminates unnecessary costs, its moat gains strength. If it treats customers with indifference or tolerates bloat, it’ll wither. Moats are not built and then stick. They’re always changing, either expanding or shrinking.

“If you’re See’s Candy, you want to do everything in the world to make sure that the experience of giving that gift leads to a favorable reaction. It means what is in the box, it means the person who sells it to you, because all of our business is done when we are terribly busy. People come in during theose weeks before Chirstmas, Valentine’s Day and there are long lines. So at five o’clock in the afternoon some woman is selling someone the last box candy and that person has been waiting in line with maybe 20 or 30 customers. And if the salesperson smiles at that last customer, our moat has widened and if she snarls at ‘em, our moat has narrowed. We can’t see it, but it is going on everyday. But it is the key to it. It is the total part of the product delivery. It is having everything associated with it say, See’s Candy and something pleasant happening. That is what business is all about.”

—Warren Buffett

Now, before getting into different ways one could go about measuring a moat, I want to expand a little more on the issue of mixing up symptoms and causes. When analyzing businesses, two of the most important biases that can turn your research into pumpkin and mice is framing and the narrative fallacy. Like an attorney who selectively gathers evidence to build her hypothesis rather than viewing the case from multiple different angles, actively looking for economic moats and thus creating upbeat stories around a company risks falling prey to the same irrationality (which, from the attorney’s perspective, is really just misaligned incentives). If you approach researching a company with the goal of you badly wanting it to have the moat you preconceive it to have, there are loads of different cherished concepts you can easily pick and choose from to build your case. A large company with bunches of plants? That probably translates to scale economies. A well-known company with stores all over the country? That probably translates to a strong brand. Sears and Kodak are examples of dominant brands that were easy to slap a bunch of advantage stickers on but failed to incrementally adapt to changing market conditions.

Survivorship bias plays a role too. Just as nature, history, and ecosystems do not agree with human conceptions of good and bad, but merely define good as that which survives and bad as that which goes under, only the surviving business tells the bigger story. History always fails to include important, variegated details and thus overexplains the path dependence that leads to a specific outcome. The territory isn’t the map. You can have two different companies of the same size using the same (on the face of it) strategy and has the same competitive advantage of scale and stickiness to the product, but one of them may trounce the other due to some singular (perhaps cultural) little factor that didn’t look so important at the time but turned out enormously important in hindsight. Merely explaining the success of the winning company using concepts like scale advantage, stickiness, and pricing power, may not be enough. By sampling only past winners, studies of business success fail to answer a critical question: How many of the companies that adopted a particular strategy actually succeeded?

What all this means is that it’s more important to learn from case studies as opposed to synthesized concepts, by several miles. When hearing a business concept for the first time—and I think here about the vastly overused concept of ‘flywheels’—you tend to take the concept at face value. You think that all you need are a couple of examples and then you can go put the framework to practice. Then you start seeing flywheels everywhere until you figure out that it never applies cleanly.

Business is an ill-structured domain. It’s messy and dependent on context that is guaranteed to be unique. As a result, every moat is unique even if they fall under the same descriptive concept. The good analyst recognizes how they’re unique by having a rich backlog of studies and experiences to pattern match against. If you treat all moats made up of the same competitive advantage the same, you cannot know how deep and wide they are. Charlie Munger may continuously preach about having a “latticework of mental models” in your head, but if you study him extensively, as I have, you will know very well that whenever Munger explains something, he does it by reasoning by analogy—analogies that carry a huge backlog from a lifetime of studying. As you study more and more cases, the concepts you’ll have at your disposal as you reach the end of this guide will evolve, and as you gain experience, you’ll become more skilled at drawing accurate conclusions while avoiding preconceived notions, tailoring your approach to the specific situation, and including appropriate caveats.

But it takes a lot of damn work. And that’s why different ways to measure a moat aren’t at all bad tools to have at your disposal.

No formula in finance will tell you whether a moat is 28 feet wide and 16 feet deep. That’s what drives a lot of market participants to dismiss their importance. They can compute standard deviations and betas, but they can’t understand moats. It’s always been the nature that intangible assets—the ones we can’t see or feel—are hard to quantify. When something is hard to quantify, accountants don’t do a good job of assessing its value, thus it doesn’t appropriately show up in the numbers.

A lot of moatsters will tell you that the only test you can conduct in assessing a company’s moat is whether its return on invested capital is above its cost of capital. And yes, that is somewhat true, however with some caveats:

So while the ROIC test is useful and should always be the ultimate, and eventual, yardstick for value creation, it isn’t an exhaustive estimation of a company’s moat-building. Here are some other useful approaches to mix it up:

The first approach I want to mention isn’t really a way to quantify a moat with absolutism but is a test of its durability. There is a theory that you can’t truly know that a moat or entry barrier exists until that moat is attacked by a well-equipped competitor and the attack is repelled. Like evolution, capitalism is a brutal place. Companies attack other companies all the time. It’s just a matter of keeping your eyes open.

The real test of Facebook’s moat happened in the early-2010s when Google initiated a giant attack against the social network and launched Google+. Starting as project “Emerald Sea”, Google didn’t just want to invent a Facebook killer; They wanted to reinvent what it meant to share information on the web. And considering their monopoly in processing web information, how could they ever fail? There are many theories as to how they did end up failing after a decade of trying, including bad management, but the real reason is found in Facebook’s fierce management and almost sect-like culture. Google had lots of reasons to fail, falling back on the search engine as the cash cow; Facebook’s social network was all it had. So of course Facebook was ready for war. The week Google+ launched, Zuckerberg put Facebook into lockdown, not letting any employee out of the building until a strategy was put down. Whereas Google was slowly growing into a bureaucracy, Facebook was still entirely run by engineers led by a ‘hacker’ ethos. If you could get shit done and quickly, nobody cared much about credentials or traditional legalistic morality. Facebook won the fight and Google+ was officially shut down in 2019. It wasn’t before Facebook was attacked by the mightiest competitor of them all, at five times Facebook’s size, that it exemplified Facebook’s moat as the definitive social network. It was also an example that Facebook’s moat at the time it mattered wasn’t just made up of network effects. Google+ was already built on the most entrenched network of all time (that between connecting users and advertisers on the web)—there was a Google Plus sign-up button practically everywhere across Google’s product, the product was simpler, and, subsidized by the Adwords cash cow, it showed no ads on the social platform—but Zuckerberg’s leadership and Facebook’s culture gave it the extra notch to win the war anyway.

My write up on Adobe is another recent example of the attack-and-repel test, although this attack was from disruption. Until Figma came along, Adobe’s moat was deemed impenetrable, having ridden almost three decades as the de facto standard in digital design. Figma changed the ball game by being browser-native and solving designers’ need for collaboration. The fact that Adobe finally attempted to acquire Figma for $20bln, or 100 times trailing annual recurring revenue, is a testament that you would need to update your assessment of Adobe’s moat’s width and depth. The attack-and-repel test became an attack-and-pay-up-to-get-us-out-of-the-way result.

“You give me a billion dollars and tell me to go into the chewing gum business and try to make a real dent in Wrigley’s. I can’t do it. That is how I think about businesses. I say to myself, give me a billion dollars and how much can I hurt the guy? Give me $10 billion dollars and how much can I hurt Coca-Cola around the world? I can’t do it.”

—Warren Buffett

Another way to measure a moat is to ask yourself how much it would cost you to take on the incumbent. Often, economies of scale require that a new entrant or challenger needs to reach a minimum viable market share to be a viable competitor to the incumbent. For example, in order for a beverage business to sustain the distribution and marketing infrastructure it needs, it pretty much has to reach a 25% local market share. A car manufacturer that prominently competes globally would need to reach 1-2% market share.

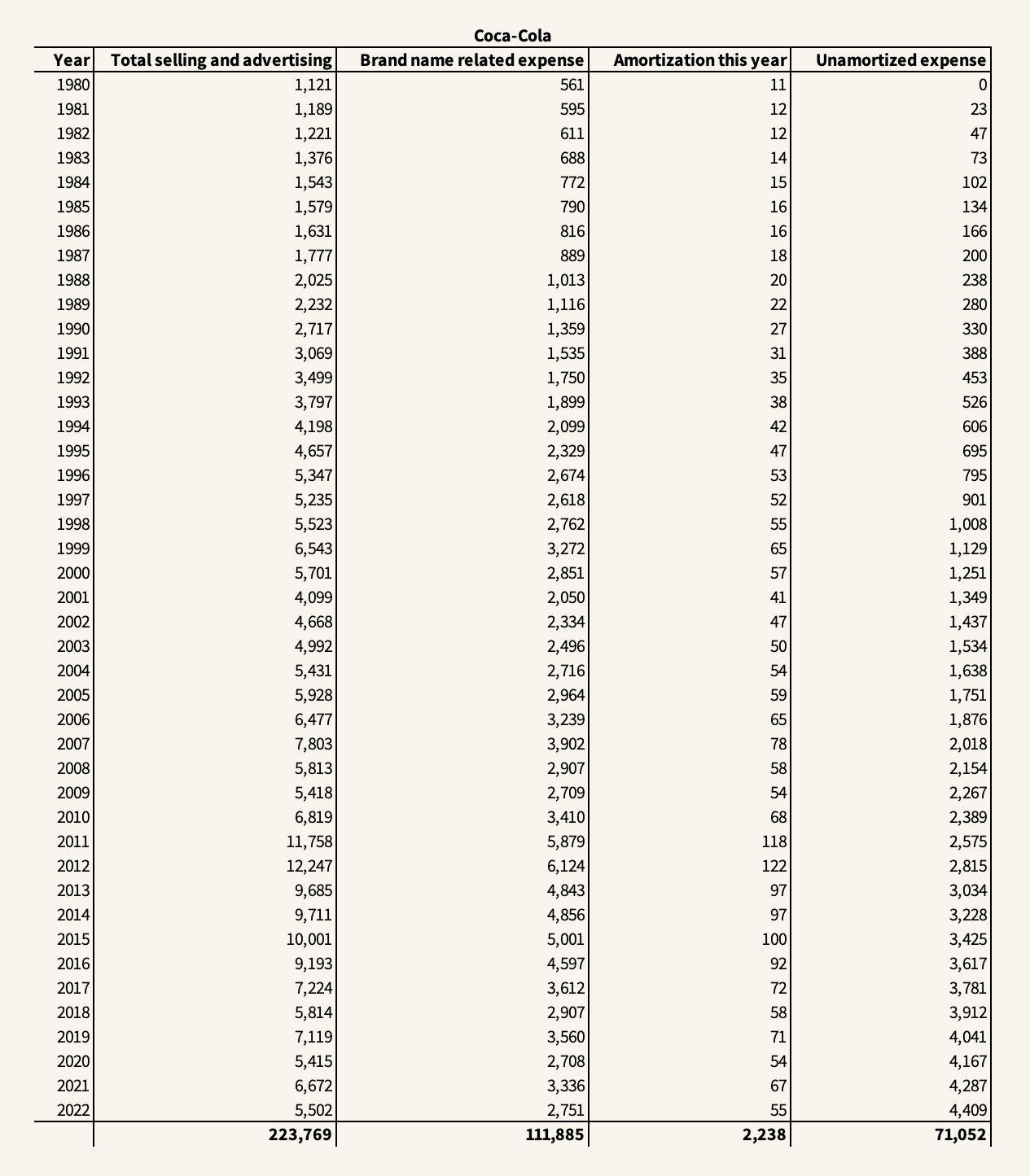

A good way to estimate what an entrant would need to reach such scale is by looking at your company’s invested capital. But as I explain in the ROIC guide, there are many assets that pass by the balance sheet, and destiny has it that the most important are often those that are directly associated with moat-building. With brand name, for instance, advertising expenses flow through the income statement, and therefore to estimate what a company has really invested in its brand name, this would require looking at the company’s advertising expenses over time, capitalizing these expenses, and looking at the balance that remains unamortized today. But when you capitalize expenses, you would also need to make a guess about the right amortization period which can be difficult and vary significantly from company to company. Of course, if a company’s moat is mostly made up of a patent that’s an easy assessment, but with something like a brand it requires you to really know the business (emphasizing my point earlier about studying loads of cases). Going all the way back to 1980, I calculated that Coca-Cola has spent a total of $224bln on total selling and advertising. If we assume that 50% can be attributed to ‘brand’ building, that’s $112bln. Now, to what degree can we assume that brand advertising spent in the 1980s still holds any value to Coca-Cola’s brand today? That’s a difficult question but I venture to guess that it’s some. If we then assume a 50-year life of the brand asset, that makes for an unamortized balance today of $71bln. Does that mean it would take you a whopping $71bln to take on Coca-Cola? Perhaps.

This brings us to the second part of the equation: Getting to a minimum viable market share may be elusive if the market position doesn’t last long. In other words, if the hands in the market are changing too much every year (if the amortization of capital invested fizzles out sooner rather than later), spending all that capital may be value-destructive. Hence, the second element of the equation regards velocity: how hard is it and how long does it take for the entrant to acquire the necessary market share? Industry stability—how much market shares change every year—reflects a host of factors, including customer captivity, proprietary technology, and so forth. A stable industry, where the hands rarely change, typically has inherent qualities of its incumbents that make it difficult for a new entrant to entrench the market. So if you have a company with a 25% market share in beverages and the hands change 0.5%/year, you’re roughly looking at a 50-year moat (then you can take Coca-Cola’s market share viscosity and see that’s it’s probably more than a 100-year moat). Contrastingly, for a car manufacturer that has 1-2% market share in an industry where hands change a whole lot more, say 1%, that’s perhaps a 1-year moat, which is no moat at all.

As a more concrete example, In my write-up on elevator companies, I mentioned how the elevator & escalator industry (E&E) is an oligopoly that’s remarkably stable and dominated by ‘the big four’. For a new company to get to a viable competitive position, it would probably need to reach >8% market share, which is extremely difficult in an industry where sales are dominated by long-term service agreements of an already installed base that grows a measly 4-5%/year. Capturing 50% of new unit installations—and that’s already stretching it—would ‘only’ accumulate to ~15% share of the installed base over an entire decade.

On the contrary, the elevator business is one that doesn’t require a whole lot of invested capital, primarily because customers pay upfront for elevators and service agreements (negative working capital) and elevator companies outsource production with only core technologies remaining in-house. In other words, there isn’t much scale advantage other than economics of density in the service market. So the elevator business is one that doesn’t require a lot of capital to get started, but it’s still diabolically hard to reach the scale necessary due to the viscosity of market shares that’s reflected in customer captivity and slow build-up of reputation. The elevator industry is one where probably 0.5%-1% of market shares change hands every year, so you’re perhaps looking at moats for the major players that would last somewhere between 15-35 years. Incidentally, that may also approach the number of years a new entrant would need to get to a viable market share regardless of how much capital it’s willing to throw at it.

If you feel comfortable trusting Mr. Market’s prices (most of the time), you could always do a relative valuation by taking the company that has a moat and comparing it to a company that clearly doesn’t. Of course, if taking Mr. Market at face value doesn’t do it for you, you can DCF both companies and subtract the difference adjusted for size. The difference is the value of the moat.

The Robustness ratio is a framework that Nick Sleep and Qais Zakaria used at Nomad to quantify the size of a moat by looking at the amount of money a customer saved compared to the amount earned by shareholders. The prime criteria for the Robustness ratio was that the customer proposition was based on price, such as what exists at Costco, as opposed to an advertising-reinforced purchase such as Nike. Usually, that’s the prerequisite you see in businesses that are subject to scale economies. The formula is really simple: If a company’s customers in aggregate save $1bln compared to the next-cheapest alternative and the company earned $1bln as well, the ratio would be 1. One dollar saved to the customer equaled one dollar retained for shareholders. The basis of the Robustness ratio is that the higher it is, the harder it would be to compete against the company on a like-for-like basis and it’s also predicated on the scale economies shared model that specifically Costco uses to build its moat. When Nomad bought Costco the ratio for 5-for-1: Five dollars saved by the customer equaled one dollar kept by Costco.

“A moat that must be continuously rebuilt will eventually be no moat at all.”

—Warren Buffett

Like the earth only orbits the sun for a finite amount of time, entropy makes sure that all moats have an expiration date. Recent research has found that the time the average company can sustain excess returns is shrinking. Moats are shorter-lived. It’s a phenomenon that’s not only attributed to high technology but is evident across a wide range of industries. Of course, the main reason is that technology has permeated pretty much every industry which has sparked a greater pace of innovation across the board. This begs the question: Are moats actually lazy, passive strategies that shun innovation? As Elon Musk once said in a quarterly earnings call: “I think moats are lame. If your only defense against invading armies is a moat, you will not last long. What matters is the pace of innovation—that is the fundamental determinant of competitiveness.”

But Musk’s claim isn’t anything new. Like the old David vs Goliath narrative, behemoths have always been attacked and overtaken by upstarts. The next-hardest thing after building a moat is not losing it when you have one. Oftentimes, poor strategic decisions or mismanagement are blamed when a moat is filled with sand, but there are other mental models, including game theory, that may help explain why moats die even in the midst of management’s best intentions.

In “The Innovator’s Dilemma”, Clayton Christensen distinguished between sustaining and disruptive innovations. Sustaining innovations foster product improvement and operate within a defined value prop. It’s about continually improving the company’s current value proposition, always providing more value to the customer than they pay for. Disruptive innovations, on the other hand, approach the same market with a different value proposition. They are divided into two types: low-end and new-market. A low-end disruptor offers a product that already exists but at a lower cost or with greater convenience, though typically inferior (think Southwest). A new-market disruptor, on the other hand, appeals to customers who weren’t even part of the incumbent’s main customer pool (think Uber).

Companies with moats aren’t usually lazy, failing to see what’s happening around them. They’re always engaging in sustaining innovations through continuous improvements of the product or customer experience. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have a moat in the first place. It’s the disruptive innovations that cause trouble, even if management is rational about responding to the threats.

For example, Christensen used the example of mini-mills vs integrated mills in the steel industry in the 1970s. Integrated steel mills, which used blast furnaces to produce high-quality steel, enjoyed a significant advantage over mini-mills, which melted scrap steel and could only produce inferior quality steel. It was an unfair fight. So what the mini-mills did was they initially focused on producing rebar, used to reinforce concrete, which was also the least attractive and cheapest market for steel. When the mini-mills became too numerous, the integrated mills exited the unattractive rebar market and as a result saw profit margins soar. However, by concentrating on making the best rebar production possible, the mini-mills gradually improved their technology, enabling them to make better steel and penetrate markets that were more profitable. Over time, and slowly, the mini-mills entrenched the integrated mills and destroyed their profitability. As Christensen noted, the integrated mills’ decision to exit the rebar market felt good initially but ultimately proved short-sighted. The moral of the story is that managers of the integrated mills arguably made a perfectly rational decision of disregarding a market that offered lower margins, was insignificant to the larger steel market, and wasn’t in demand by the company’s most profitable customers. They listened to their customers, practiced conventional financial discipline, but were disrupted anyway.

The thing is, if an incumbent faces sustaining innovation, it isn’t in much danger assuming that its moat is strong. If a new competitor comes along with a sustaining innovation, incumbents are highly motivated to defend their turf and, as Christensen suggests, it’s very rare to see an incumbent lose this battle to a challenger. But as in the case of the mini-mills, once the challenger is a low-end disrupter in what is already an unattractive market for the incumbent, the motivation is generally to flee that market. Likewise, if it’s a new-market disruption, in which there isn’t any proof-of-market and returns on capital spent, the incumbent will be motivated to disregard the threat. Considering the incumbents’ many options for capital allocation, including buying back shares, it can’t keep throwing money around at every potential disruptive threat since for every succeeding innovation, there are probably hundreds that wouldn’t succeed.

So the idea is to operate in a field that’s less prone to disruptive innovation. The Lindy effect plays its part here. Usually, if a company gains a moat very quickly, it’ll have to worry about losing it quickly, too. When an industry is unstable, the hands trade fast, even for the players deemed safe. Google’s search engine, one of the biggest profit pools in history, is an example of a mighty moat that’s obvious to everyone. But it’s also a moat that’s only a little over 20 years old, a fraction of something like Coca-Cola’s moat. Now generative AI and Microsoft’s determination to attack are going to show how impenetrable Google’s search moat really is. For Google to respond to disruption and perhaps let go of a technology and business model that has pumped out profits consistently for two decades is truly an ‘innovator’s dilemma’.

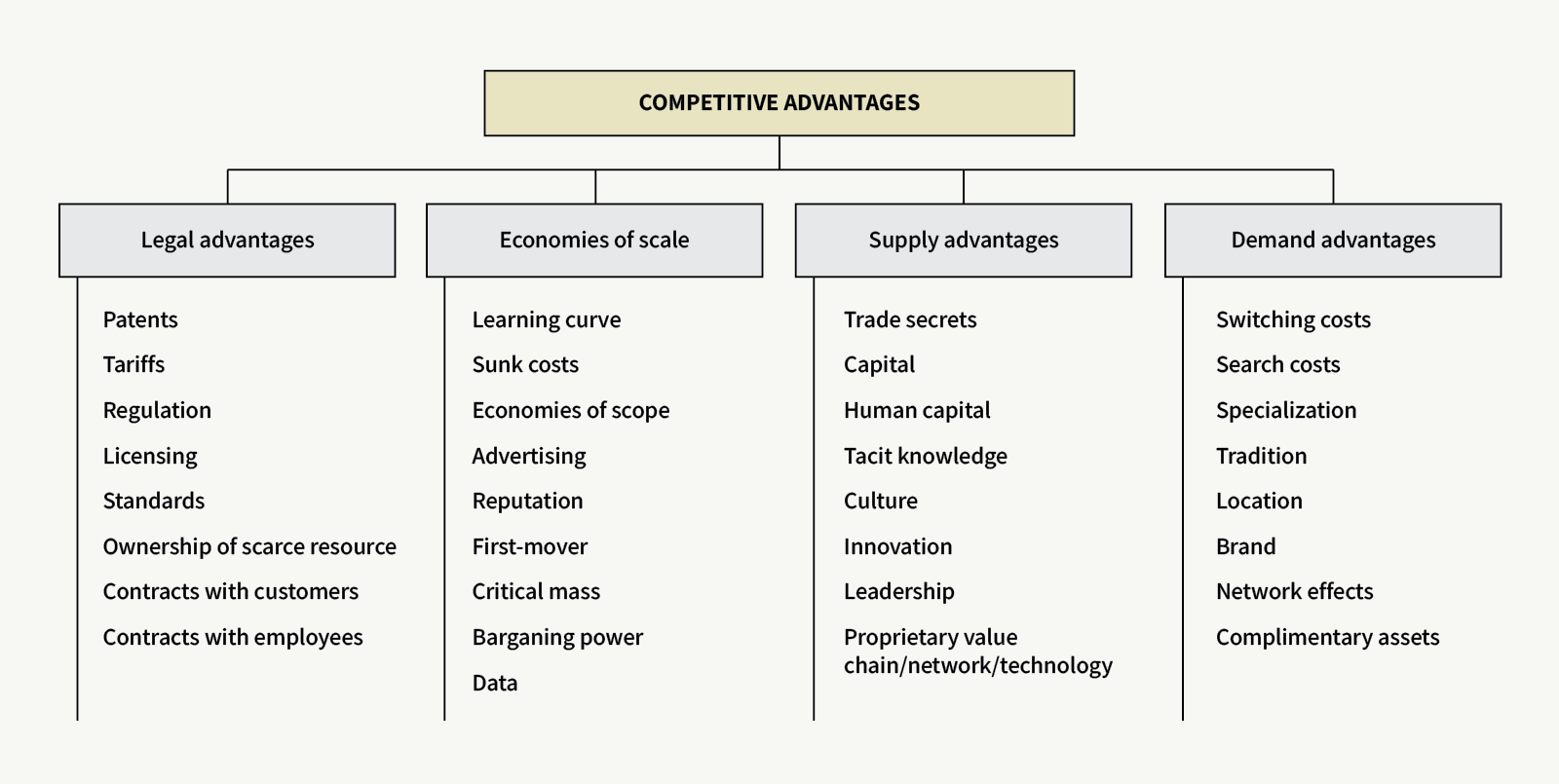

The takeaway I want to emphasize throughout this guide is that when looking for durable moats, it’s important not to overapply the types of competitive advantages that follow. Reality is almost always more nuanced than single competitive advantages and important other factors are hidden behind the great narrative. I think ‘brands’ are the best example because it’s usually considered the strongest foundation behind a moat. But the reality is that some of the most well-known global brands, and I’m especially thinking of many consumer car brands here, consistently earn below or barely earn their cost of capital, often because they have no pricing power or emotional connection. In other words, there is weak correlation between brand ranking and economic return. A truly durable moat is a rare creature and requires many advantages moving synchronously in the right direction. It’s what Munger calls the Lollapalooza effect. And if there’s one other rule it’s that no single competitive advantage works in moat-building if the right culture isn’t there. Culture is overarching. So, with that out of the way, here’s an extensive list of competitive advantages that can create a company’s moat.

My goal with this list is to uncover each advantage, one at a time, for future articles, where I look at specific case studies that might aid you (and me) in systematically expanding our set of patterns in finding moats—of the truly durable kinds. So bookmark this guide as I may continuously add new case studies to each competitive advantage.

Government policies and local law enforcement can act as meaningful sources of competitive advantage. And sometimes, the regulations cast onto one company, perhaps due to its size, can be a source of competitive advantage for another.

Patents

The intent of a patent is to allow an innovator to protect their innovation. Patents do not discourage innovation, but they do deter entry for a limited time into activities that are protected. Patents can be used as cynical moat-digging campaigns as long as they last, but once they expire, it’s gone.

Tariffs

Tariffs can be advantageous for companies in industries where there is significant international trade and where tariffs are imposed to protect domestic producers.

Regulation

While regulation can create challenges for companies, it can also create a moat by making it more difficult for new competitors to enter the market, giving established players a competitive advantage.

Licensing

A number of industries require a license or certification from the government to do business which can be costly and time-consuming to get.

Standards

Macro-wide standards can be reinforcing, meaning that all the business often accrues to the largest players. It’s strongly related to network effects. For example, a debt issuer has little choice but to pay Moody’s for a rating if it hopes to get a fair deal in the market.

Ownership of scarce resource

Ownership of a scarce resource may cut off competitors from the same opportunity. For example, after WWII, aluminum producer Alcoa signed exclusive contracts with all of the producers of high-grade bauxite, an essential material in aluminum production. But other than land and raw materials, a scarce resource could also be a distribution channel. For example, Salesforce has exclusive integrations with Google Analytics 360. In turn, Google pays Apple $16-20bln/year to be its default search engine.

Contracts with customers

Companies can secure future business through long-term contracts that may lock the customer for years but have the added benefit of reducing search costs for both the supplier and the customer. In the 1980s, Monsanto (NutraSweet) and Holland Sweetener Company both produced aspartame, a sweetener. When the aspartame patent expired in Europe in 1987, Holland entered the market and competed with Monsanto, leading to a 60% decrease in aspartame prices and losses for Holland. However, Holland had its sights set on the U.S. where the patent would last until 1992. To gain an advantage, Monsanto signed long-term contracts with the biggest buyers of aspartame, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, effectively excluding Holland from the U.S. market. Here’s the important lesson: buyers may want multiple suppliers, but they may not use them.

Contracts with employees

Non-competes and NDAs can be sources of advantage for companies operating in industries with highly skilled labor.

In moat-building, economies of scale are critical and are often the driver behind the rest of the competitive advantages through feedback loops. But economies of scale can also be the explanation for how some moats die through bureaucracy, complexity, or input scarcity. As there are scale advantages, there can also be scale disadvantages.

Learning curve

The more you do something, the better you get at it, and the cheaper you can do it. The learning curve is particularly relevant for businesses with high fixed costs but is also affected by factors such as divisibility, like whether production can even be scaled (if a bakery wants to service a new region, it must open a new bakery, add trucks, and hire more drivers), complexity, like whether processes can be imitated, and rate of change in process costs, like whether costs can decline over time as a result of technological advances (the cost of building an e-commerce store today is negligible compared to twenty years ago).

Sunk costs

High exit costs discourage entry from new entrants. If getting into a business requires a huge investment with specified assets, these sunk costs can act as an advantage for the incumbents.

Economies of scope

When a company reaches a certain scale, its size can enable it to grow horizontally rather than vertically while achieving synergy between its horizontal activities. For example, there can be significant spillovers from R&D. When Pfizer sought a drug to treat hypertension, its research led it to think it might treat angina, but then found the unusual side effect which led to the blockbuster drug, Viagra.

Advertising

Some advertising channels, like TV throughout the latter half of the 20th century, are more efficient at scale. When TV came in, companies with strong brand names prospered.

Reputation

Reputation is built slowly over time and may be one of the strongest moat foundations besides culture. It’s subject to economies of scale because a strong reputation feeds on itself. It can also take the form of a cynical reputation. If a company gains a reputation for being ruthless and ready to fight at the least provocation, it can deter the competitor from attacking.

First-mover

Being first to reach minimum viable scale can either make it or break it for a company, especially if it’s operating in a winner-take-most industry.

Critical mass

Related to the first-mover advantage, once a company has reached a certain minimum viable scale, it may be significantly harder for a competitor to reach the same scale because the spot has already been filled. Critical mass is especially foundational to moat-building when coupled with network effects.

Bargaining power

Scale often means power over suppliers and can allow a company to source cheaper. Kellogg’s and Campbell’s moats have shrunk over time precisely because superstores such as Walmart have grown. However, bargaining power may also provide some value to the supplier. Large firms are lowering their supplier’s opportunity costs by providing the supplier with better demand information.

Data

Tied strongly to switching costs, a data advantage sometimes makes it hard for a company or individual to switch vendor. For example, people who use Spotify and listen to a lot of different music may find Spotify’s algorithmic recommendations from thousands of hours listened so useful that they would never consider switching to other music software.

Trade secrets

Companies may choose to keep trade secrets instead of filing patents, especially in the case of software companies where publishing algorithms can make it easier to copy. However, this strategy can leave the company vulnerable to competitors who could patent the same invention and sue the original founder for infringement. While trade secrets can allow litigation against employees who leak confidential information, it does not provide legal protection against competitors. There’s a wonderful case story named “Wohlgemut’s Secret” on trade secrets in John Brooks’s book, “Business Adventures“.

Capital

Access to capital, or a strong ability to raise it, is a significant advantage for companies operating in industries where capital is continuously needed to fund growth. The advantage is especially useful in times of distress since access to capital may allow making significant strategic decisions or acquisitions that reinforce the moat as lesser-able competitors get wiped out.

Human capital

A shortage of highly skilled labor can be a significant advantage if you’re a company that has a strong workplace reputation and rigorous hiring processes like Goldman Sachs or Google.

The difficulty of copying knowledge calibrated through experience and lots of feedback loops is like trying to masterly play the piano by watching someone else’s fingers move. Information theory and the closely related field of thermodynamics describe how easily patterns tend to gravitate toward disorder and information loss. Tacit knowledge is subject to conditional entropy through transmission. Therefore, companies having a significant knowledge advantage have little risk of losing it unless they lose their human capital.

Culture

You know your culture is powerful when competitors know what you’re doing, how you’re doing it, and they still can’t copy it.

Innovation

Only the paranoid survive.

Leadership

If culture is the machine of the company, leadership is the machine operator. When evaluating management it’s important to separate process from outcome. Having a good process does not always guarantee a positive outcome since many factors such as luck, competition, and technology can influence outcomes. Therefore, it’s better to evaluate management based on the processes they use rather than the outcomes they achieve in the short term.

Proprietary value chain/network/technology

Amazon is a relentless moat builder through proprietary value chains and networks. The company’s proprietary value chain spans anywhere from the design and development of its own hardware from (Kindle, Alexa devices, and the Graviton data processor chip), to its own logistics and delivery network (Amazon Prime and Amazon Flex), to its own cloud computing services (Amazon Web Services).

Switching costs

Switching costs can arise from many sources, including contractual commitments, durable purchases, brand-specific training (a good one), information and databases, specialized suppliers, loyalty programs, and so forth. Bloomberg’s iron-strong moat in financial data software is reinforced by the extensive training financial professionals undergo, starting at university, to learn the Terminal. Habit is a strong contributor to switching costs, too. For example, customers rarely change their primary banking account which makes it difficult for large banks to steal business from small banks despite having scale advantages.

Search costs

Related to switching costs, search costs are largely attributed to experience goods that may be technologically complex. For example, Aspen Technology, a software business that offers process optimization to the energy, chemicals, and engineering industries, helps enterprises optimize their manufacturing processes, reduce costs, and improve efficiency which heavily reduces their search costs. And once the enterprise has invested in AspenTech’s software and deeply integrated it into its manufacturing processes, it’s not easy to switch.

Specialization

The killer of scale advantages is specialization. Munger once wrote: “We are the largest shareholder in Cap Cities/ABC. And we had trade publications there that got murdered—where our competitors beat us. And the way they beat us was by going to a narrower specialization. We have a travel magazine for business travel. So somebody would create one which was addressed solely to corporate travel departments. Like an ecosystem, you’re getting narrower and narrower specialization. Well, they got much more efficient. They could tell more to the guys who ran corporate travel departments. Plus, they didn’t have to waste the ink and paper mailing out stuff that corporate travel departments weren’t interested in reading. It was a more efficient system. And they beat our brains out as we relied on our broader magazine. Occasionally, scaling down and intensifying gives you the big advantage.”

Tradition

The durability of tradition must not be underestimated. Famous for its traditional Chinese liquor called baijiu, Kweichow Moutai, which at one point was China’s most valuable company, has built a deep moat rooted in Chinese tradition with a history that spans more than 2,000 years.

Location

Related to economies of density, a locational advantage can either derive from ease of availability or from achieving economies of density in operations by having locations, whether that’s plants, retail stores, or distribution hubs, close to each other. By aggressively targeting high-traffic, convenient locations, McDonald’s has a large locational advantage on a global scale, blocking competitors’ ability to secure equal prime real estate.

Brand

Compared to something like patents, brands are more fragile. However, they don’t have a fixed expiration date. A brand becomes valuable once it becomes share-of-mind. Buffett once said that Eastman Kodak’s moat was just as wide as Coca-Cola’s. “They are promising you that the picture you take today is going to be terrific 20 to 50 years from now about something that is very important to you. Well, Kodak had that in spades 30 years ago, they owned that. They had what I call share of mind. Forget about share of market—share of mind. They had something—that little yellow box—that said Kodak is the best. That’s priceless.” But time showed that Kodak’s brand moat had an expiration date: “They let that moat narrow. They let Fuji come and start narrowing the moat in various ways. They let them get into the Olympics and take away that special aspect that only Kodak was fit to photograph the Olympics. So Fuji gets there and immediately in people’s minds, Fuji becomes more into parity with Kodak.”

Network effects

There are two types of networks: a hub-and-spoke network, where a hub feeds the nodes (examples include most airlines and retailers), and an interactive network, where the nodes are either physically or virtually connected to one another (Visa and Mastercard). Network effects do exist in the former but can be vastly more explosive in the latter.

Complimentary assets

Not all business relationships are based on conflict. Sometimes, companies outside the purview of a firm’s competitive bubble can heavily influence its advantages. Electric car manufacturers and charging station makers are an example of complementors. The value of both electric cars and charging stations increases as there are more charging options. The more electric vehicles there are on the road, the more valuable charging stations become.

This is a complete list of articles I have written on the subject.

A complete guide to pricing power and how to identify it in its most durable form.

Spotting an economic moat in a business before the fact is not an easy thing to do. Here are seven signs to start off from.

Here’s Charlie Munger’s way of explaining how lollapalooza effects from the simplest academic models create the success and trajectory of Coca-Cola.

Knowledge and know-how can act as an almost indestructible moat for a company’s competitive position and growth prospects. But there’s also a large risk of losing it coming from within an organization.

© 2023 Junto Investments, all rights reserved. The content provided on the Junto Investments (“Junto”) website is for informational purposes only, and investors should not construe any such information or other content as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained on junto.investments constitute a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer by Junto or any third party service provider to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments in this or in any other jurisdiction in which such solicitation or offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. See our Terms, Privacy Policy, and Disclaimer.