A couple of years ago, for those under the age of forty in the US or Europe, inflation was a remote concept—something politicians and experts talked about but not something central to their lives. For those on the other side of forty, inflation was a latent threat waiting to wreak havoc on savings and expose weak points throughout the economy and societies. Investors old enough to remember the 1970s reminisce about a decade of staggering inflation but only in hindsight. At the end of the 1960s, no investor had any sure reasons, other than temporary OPEC-related factors, to believe that they were heading into a high-inflation decade. In fact, what happened during the 1970s was that expected inflation continuously lagged actual inflation and this very fact was the primary driver of the decade’s secular bear market.

This is an important point because while inflation is an integral part of investing and valuation, it’s also the most unpredictable of all macro factors to incorporate into stock prices and intrinsic value. To understand inflation’s impact on asset values, you would have to break it down into its expected and unexpected components. The former entrenches your expected investment return (and is what drives interest rates) and the latter plays out as a risk factor. By itself, higher inflation isn’t dangerous if it’s predictable since that would allow investors and businesses to factor it into their decision making, with investors demanding higher interest rates on bonds and expected returns on stocks and businesses raising prices on their products/services to cover expected inflation. It’s the unexpected inflation that catches people, businesses, and central banks off guard, and the problem with higher inflation levels, of course, is that inflation numbers swing by more points, increasing the number of surprises and uncertainty around the median. Inflation is not only a monetary phenomenon; it’s a psychological phenomenon as well. Once it’s out of the bottle, it drives every other topic out of the conversation which alters human and business behavior, like stockpiling inventories and prioritizing short-term gains over long-term productivity.

For those that have been wary of inflation for years, it has meant crying wolf in a decade-long environment that merited barely a mention of its impact. And yes, there were various arguments for why that would continue. As the economy climbed back from the events of 2020, many believed the unprecedented scale of monetary and fiscal policy wouldn’t lead to high inflation because the economy had excess capacity. Others believed that an increasing shift to a tech-driven economy would remove inflationary pressures altogether. But the largest contributor to low expected inflation was that an entire decade of low, stable inflation and Fed interventions had operantly conditioned many to not even imagine a high-inflation environment. The conditioned idea of persistently low interest rates not only affected inflation expectations but also wormed its way into investor mindset, market projections, valuation models, leverage ratios, debt ratings, affordability metrics, housing prices, and management behavior. Correspondingly, persistent efforts to curtail downside volatility, prevent company bankruptcies, and delay consequences even through the great lockdown swayed investors to increasingly behave as though nothing bad could ever happen.

As the consequence of unexpected inflation now showing its true colors and flowing through many global economies, let’s go through what impact the phenomenon has on corporate behavior and company value, first by the macro view. The intuitive mental model of unexpectedly high inflation is that it hurts bonds and that stocks in turn act as hedges because a bond’s cash flows are fixed whereas a stock’s aren’t. Historically, though, that logic has been broken down. History has shown that stocks have done worse during high and increasing inflation while having done increasingly well during low and deflationary periods. In other words, unexpectedly high inflation has never been good news for either bonds or stocks in general.

The explanation, on the other hand, isn’t as convoluted. Stocks in general are pressured by increasing inflation for two simple reasons: 1) companies’ costs of capital increase more than proportionately since increasing inflation translates to increased uncertainty which in turn translates to increased risk premiums, and 2) taxes aren’t inflation neutral, meaning that tax benefits from tax-deductible depreciation, which is based on historical cost, become less valuable with inflation, in effect increasing the effective tax rate for companies.

Those two reasons at the same time explain why not all firms are affected equally. While the majority of stocks are negatively affected by unexpectedly high inflation, a select group isn’t. To further explain, from the micro view of a single firm, you can describe the value of a stable growth firm as:

(Revenues – Operating Expenses – Depreciation) * (1 – Tax Rate) / (Cost of Capital – Stable Growth Rate)

If inflation jumps by several percentage points, everything in the equation would have to rise proportionately for intrinsic value to be unaffected. Revenue, operating expenses, and depreciation would have to increase at the rate of inflation. The tax rate would have to remain unchanged and the discount rate would need to increase by the same percentage.

Now, if you divide the equation into the numerator and denominator, you have the expected free cash flow as the former and the expected discount rate as the latter.

As unexpected inflation surfaces, to protect operating margins, companies would not only need to pass through inflation in the prices of their products and services but at the same time resist input costs rising at a faster clip, meaning that companies with significant input costs that are more exposed to commodities will see margins decrease relatively faster. As for taxes, as explained before, the code is written to tax nominal income, with little attention paid to distinguishing between real growth in income versus growth from inflation, thus increasing the effective tax rate. Lastly, companies with longer-term and more rigid investments are more likely to invest less during uncertain inflation, putting their long-term value at stake to deal with short-term inflationary pressures.

As for the expected discount rate (the denominator), high unexpected inflation first increases the failure risk, especially at cash-flow-negative companies, originating in the reality that interest expenses increase and default spreads widen when inflation increases. Secondly, while inflation increases the risk-free rate, it should, in theory, not affect the equity risk premium. That isn’t the reality, though. As explained earlier, higher levels of inflation mean wider swings, translating to higher uncertainty, which in turn increases the equity risk premium, proportionately more for riskier firms.

The verdict makes sense. To resist all the gravitating pressures of unexpectedly high inflation, which is not a bit easy, you would have to be in the minority of companies that are not riskier during periods of unexpected inflation. And to be in that minority of companies, the following would have to apply:

- You’d need to be able to raise the price of your products and services at or above the inflation rate.

- You’d need to operate with limited input costs that increase at or below the inflation rate.

- You’d need to have a business model that requires low or short-term, reversible capital investment.

- You’d want a stable earnings stream with little debt leverage (and preferably at fixed interests).

The overarching term for such a company is one that has pricing power. The misunderstood but widespread first-order thinking about pricing power is that only point number 1 applies (the ability to raise prices in conjunction with inflation), but the fact is a lot of companies can raise prices when consumers expect them to do so without much concern for losing business. But that misses the forest for the trees because even if you assume companies to be stable and deliver price increases in line with inflation, you may still have the drag in value caused by even higher input costs, risk premiums, failure risk, and effective tax rates. If raising prices means you would also have to throw more capital into the business to earn the same return, it’s no pricing power. As Ben Graham writes in The Intelligent Investor: “The only way that inflation can add to common stock values is by raising the rate of earnings on capital investment”.

Because business is an ecosystem, inflation effects on different companies are fluid, not static; as one company struggles, another company benefits, and as the failure risk increases for one company, it falls for another. That’s why some companies are able to benefit competitively from inflationary environments. Pricing power is a trait that can be utilized in inflationary environments to grab market share from struggling competitors and/or buy them out to use as platforms for growth, further strengthening their competitive position through scale economies. In fact, pricing power is so imperative to a company’s economic moat and competitive strategy that Warren Buffett once said it’s more important than good management.

True Pricing Power Is Rare

But identifying and understanding pricing power that’s also durable is the more essential matter. If a company’s moat involves pricing power that results in unparalleled profits, it’s tempting to think pricing power is this unalloyed good. However, pricing power is a symptom of a lot of things working in the company’s direction, not the cause of its moat.

Consider for a minute what the opposite of pricing power is. One example is a mining business that sells a commodity. When demand for a pure commodity drops, prices go down along the cost curve and even small changes in demand can cause significant price decreases. For example, in the period of 2013-2015, as iron ore demand went from +4% to -2% in conjunction with China attempting to curb pollution and excess steel capacity, it led to a two-thirds drop in iron ore prices. Even the largest and most diversified iron ore miners saw sales drop by the same proportion, earnings decline even more, and debt levels rise to uncomfortable levels. The best operators cut costs and deferred expansion, while others had to sell their most valuable assets. The result was permanent destruction of capital across the board. In the commodity business, it is possible to gain an advantage, including geographical niches and excellent cycle management, but in the end, it’s a business that has no pricing power.

Now consider the other side of the spectrum where you have a near-monopoly that is at the same time a utility-like business. For much of the 20th century, cable TV was that kind of business. For the streamers who already forgot what cable TV was like, what providers did was they showed a preprogrammed list of entertainment and slapped on bunches of ads in between. And since they bundled channels together that they know customers wouldn’t be willing to pay for on their own, they could charge a high and increasing price for the bundle. While this coerced pricing strategy does work for some time by empirical evidence, it’s not the durable kind of pricing power you should looking for. Indeed, genuine willingness, where a zero-sum game of winners and losers transcends to a better place, creates the most durable kind of pricing power. Not coercion.

Another more extreme example of coerced pricing power is that which you may rename to ‘price compulsion’. In 2015, Martin Shkreli, then-CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, gained control of Daraprim, a life-or-death drug that had been used for many years to treat a life-threatening parasitic disease. Once Shkreli gained control, he significantly increased the price of a single pill, raising it from $13 to $750. This sudden ‘pricing power’ caused widespread outrage as it led to a substantial increase in the overall cost of treatment, from $1,000 to $63,000. The situation garnered attention when Shkreli appeared before Congress and made controversial remarks (like calling lawmakers imbeciles). Of course, what happened was that Shkreli was ordered to return the profits reaped from the price hike and was barred from participating in the pharma industry for life. The controversy heightened attention to the pricing of essential medication, eventually leading to the fall of another pharma company, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, which business consisted of exactly that; serial-acquiring existing drugs and hiking the price, which generated substantial, but eventually perishable returns to shareholders.

Other types of coerced pricing power that may lead to less-than-great looking long-term outcomes for a business include contract lock-ins, retaining your business through paperwork rather than by choice, or predatory pricing, blitzscaling by under-pricing the market and increasing prices once the competition has been decimated and customers have no choice.

But there are also positions of pricing power consisting of causes/advantages that create ‘good’ excess returns but where the causes may not actually be durable. This even includes widely praised advantages such as network effects, which may lead to some form of monopoly provoking regulatory crackdown or consumer backlash over the long term, or brand, which in itself doesn’t prevent the entrance of new competitors with a different angle or purpose nor protects the company from disadvantages of scale. Moreover, because not all moats are created equally, misidentifying your competitive advantages can be dangerous, and if you don’t know, down to the bones, the actual advantages that make up your moat, it’ll not only be difficult to nurture it and widen it, but you may even put it at risk with your actions. Cola-Cola learned the lesson first-hand in 1985 when it launched “New Coke” on the misguided notion that taste was the decisive factor for the consumer (Pepsi-Cola showed better ratings in blind taste tests until Coca-Cola changed the recipe enough to win the tests) when in reality, the taste was an irrelevant factor to Coca-Cola’s dominance. New Coke continued as a separate line alongside the original recipe as it was rebranded to “Coke II” in 1990, and it took an entire 17 years, until 2002, for Coca-Cola to shut it down completely.

The reality is that true and durable pricing power is rare and even some companies with the strongest pricing powers, like Coca-Cola, sometimes misidentify the real causes behind it. Especially during inflationary periods, many investors can fall into the trap of thinking a company has it until things go the other way. What matters is the durability of compounding growth; whether a company’s pricing power will be able to carry it for years and years, across the entire business cycle, rather than fizzle out, either due to the fleeting nature of its short-term advantage or due to low entry barriers. Since the vast majority of companies don’t have pricing power in the true sense of the term, people are not used to seeing it and therefore fail to appreciate its math (if a company earning 15% operating margins raises prices just 5%/year, while holding volume and expenses steady, its operating income would nearly triple in five years). It’s a simple thing but it requires many things working in the same direction to make it stick.

But if true and durable pricing power is rare, who is to say one is able to identify it out of thousands of businesses claiming to possess it? Luckily, there’s a helpful framework, first presented by Adam Brandenburger and Harborne Stuart in their 1996 paper titled “Value-based Strategy”, for thinking through what might cause a company to contain true pricing power.

The Value Stick Framework

“The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price 10 percent, then you’ve got a terrible business.”

—Warren Buffett

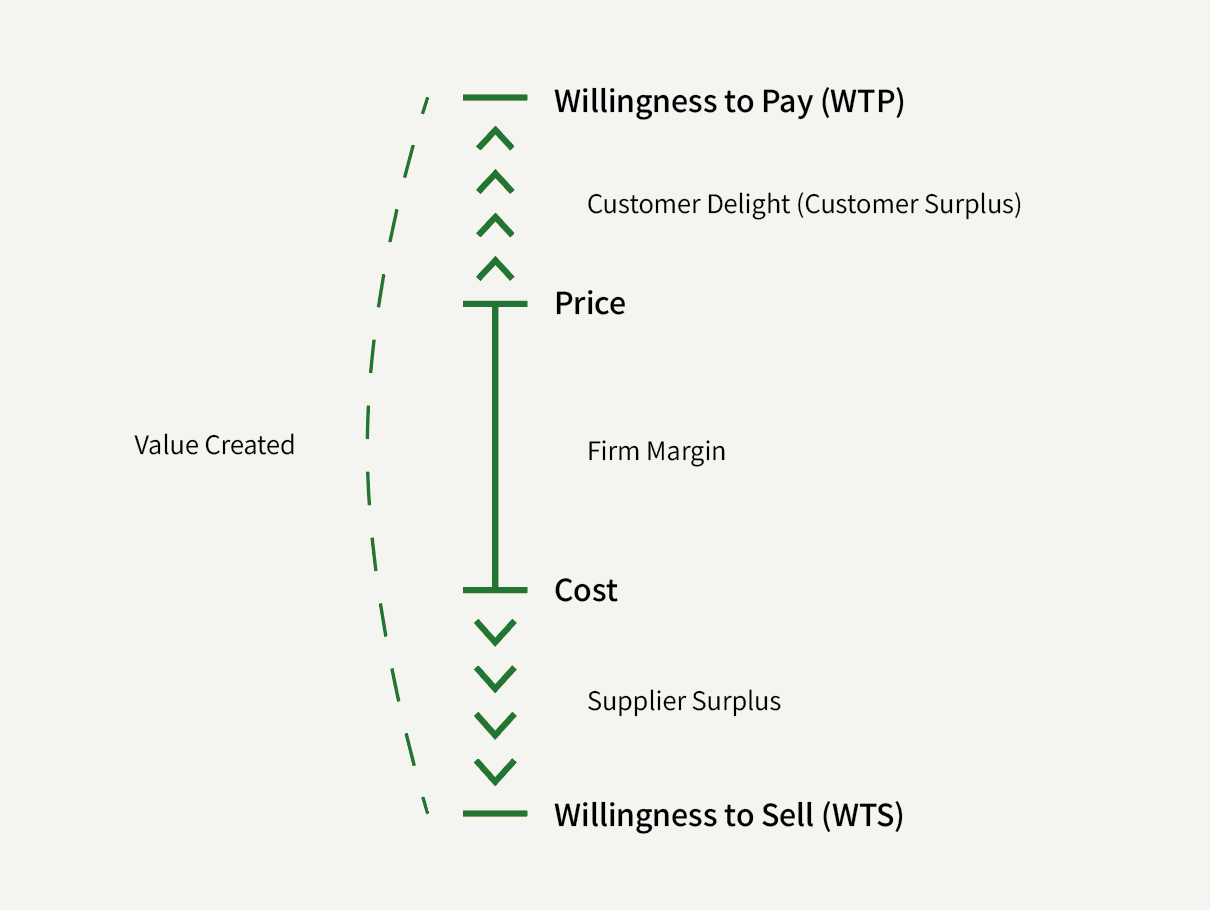

If there’s one common pattern for all companies attempting to venture into systematic price hikes in the name of ostensible pricing power but end up failing, losing market share, and damaging their reputation, it’s this: they all go too close to or cross the customer’s willingness to pay (WTP). And while that may read like an obvious, maybe even pointless, statement, the importance lies in the part of “getting too close”. Brandenburger and Stuart presented their simple model of value creation that looked beyond just shareholder value but included buyers and suppliers in the value creation process as well. It looks like this:

Four numbers are involved in value creation:

- The willingness to pay (WTP) is the maximum amount a customer would pay for a product or service.

- The price is what the firm charges for that product or service.

- The cost is what the firm incurs to deliver the product or service.

- The willingness to sell (WTS) is the minimum amount a supplier (the most important are usually the employees) would accept to provide the product or service.

WTP minus price reflects consumer surplus, cost minus WTS reflects supplier surplus, and price minus cost reflects value creation for the firm. Total value creation is the difference between WTP and WTS.

To build a mental model of how the Value Stick framework plays into the durability of pricing power, consider two different companies: Company A prices its product far below WTP, but still above cost, and Company B tries to capture as much value as possible (make lemonade of every lemon, if you will) and prices its product just below the customer’s WTP. If Company A delivers $4 of value, charges $2, and incurs the cost of $1 to do it, Company B delivers $4 of value but charges $3.9 at the same level of cost. Company B grabs a lot of value for itself while Company A creates a large customer surplus.

At first glance, you’d see better economics for Company B than Company A. It would generate significantly higher gross margins, translating to high returns on assets, which in turn would allow the company to reinvest more money into new plants, hire lots of MBAs, and so forth in an effort to create more sales. The only problem is, as Company B gets close to the customer’s WTP, the price elasticity of those customers starts to increasingly widen so that the marginal price increase leads to a larger loss of demand. Sometimes, the natural volatility of the average customer’s WTP would cause it to occasionally dip below the price. As customers are faced with more options, Company B would need to continuously innovate and find new ways of differentiation to justify the price. As the company tries to squeeze the price just a little higher, die-hard customers turn sour, innovative new entrants swoop in at lower prices, and the retention rate drops with the lifetime value. In its efforts to derive as much value as possible in the short term, Company B fails to expand its moat and eventually sees its large reinvestment efforts create returns below an average savings account.

Company A, on the other hand, has psyched customers who feel their needs are put first—which they are. The company’s product provides a whole lot more value than it charges for it. The company earns the reputation it gains by splitting its value with the customer. Meanwhile, instead of focusing on how to create more sales first, Company A focuses more on how to delight its customers to increase WTP even more. When Company B asks “Where should we price?”, Company A asks “How can we create more value for the customer at the same price?”. In other words, Company A constantly focuses on extending its compounding runway by creating ever more customer surplus. In keeping the price low compared to value, the company expands its addressable market by capturing those near customers that have a lower WTP than the main customer group, spurring additional volume through scale economies that allow it to reduce costs per unit so that the WTP-price ratio can be maintained. As WTP increases by a factor every year, Company A makes sure to maintain its WTP-price spread by hiking prices steadily by the same factor. Customers are continuously delighted, Company A slowly utilizes its pricing power, turning it into a durable compounder. For Company B, it’s game over.

The Value Stick framework is difficult to unsee once you’ve seen it. I often encounter analysts who claim that the best quantitative measure of pricing power is the gross margin. And while it’s true that a relatively high gross margin, more notably the margin stability and gross profitability (which is gross margin scaled by the assets), can act as an indicator since that would mean the company can charge a lot for its offerings, what the Value Stick framework tells us is that it’s not necessarily the case. Two companies currently earning the same gross margin in the same industry can possess vastly different pricing powers.

Products that possess true pricing power have an endowment effect attached to them. In a 2018 behavioral public policy paper on Facebook, Cass Sunstein surveyed a bunch of individuals about their use of various social media platforms and what they would be willing to pay for them on a monthly basis after having so far used them for free. But not only did he ask what they would pay, he also asked what amount they would be willing to accept (WTA) to never use the platform again. In line with the endowment effect, the results showed huge differences between WTP and WTA, a phenomenon Sunstein labeled a ‘superendowment effect’. For Facebook, the average WTP came in at $17 but the WTA came in at more than 5x that at $89. For LinkedIn and WhatsApp the ratio of WTA/WTP was less, at 3.8x and 2.9x, respectively.

In a CNBC interview, Warren Buffett once stated that the average Apple consumer’s WTA to never being able to buy another iPhone would run to $10,000 and that consumers would rather give up their second car than not be able to use the iPhone. Once a customer is hooked in a company ecosystem with pricing power, their value can skyrocket, which is why you often find early-stage growth companies ‘gamble’ with their pricing power in order to start off with a large existing customer base—like when Disney launched Disney+ at under half of the price of Netflix to amass nearly 30mn subscribers the first three months it was launched in the US. But even so, focusing too much on the price that Disney+ charges and how many subscribers it amassed would miss the forest for the trees. For Disney, the real opportunity lay in increasing customer surplus that would allow its new venture to enforce the brand strength of the rest of Disney’s businesses—from merchandise to live events, mobile games, and more. Disney+ allowed Disney, for the first time ever, to interpret exactly who engages with their content, at what frequency, in what categories, and through which characters, helping it improve the customer’s WTP for many years forward.

What all this means is that the current price a company charges and how much it raises it from year to year doesn’t tell you outright what its pricing power is. What matters is the ratio between the WTP and price, also commonly known as ‘latent’ pricing power. The higher the ratio, the harder it is to compete with the business on a like-for-like basis. Now, of course, the Value Stick framework is a descriptive model that isn’t rooted in exact science since WTP isn’t the same from customer to customer, and sometimes the difference in extrinsic and intrinsic factors that could come from anything—utility, pleasure, status, even irrational confusion—can cause the variance to become very wide.

However, when the value prop behind a customer’s WTP is solely monetary, meaning the price leads to a specific number of savings for the customer, it’s a rather simple calculation.

Take for example Moody’s and S&P Global, which together hold ~80% market share in credit ratings and have become the bona fide benchmark by which market participants, from investors to regulators, peg the creditworthiness of one debt security against another. The standards that Moody’s and S&P Global uphold are so intertwined in the financial system that they underpin the risk weightings banks assign to assets to determine capital requirements, dictate which securities a money market fund can own, and, by ostensibly communicating the credit risk embedded in debt securities, make it easier for two parties to confidently price and trade, enhancing market liquidity. So from the customer’s perspective, the value prop is very simple: If you want to issue debt and you decide not to get it rated, you’ll not only get a bad deal in the market, you’ll also be placed in a grey bucket outside the financial system.

Of course, a necessary utility like that, protected by self-reinforcing standards, results in lots of pricing power for Moody’s and S&P Global (the average issued bond has 2.4 credit ratings). The question is: how much? Well, it’s a simple problem. If the difference in savings for an issuer of a $500mn 10-year bond is 30bps per year if it pays for a credit rating as opposed to if it doesn’t, that translates to $15mn pre-tax savings over the life of the bond. Assuming the issuer is somewhat investment grade, it may only pay 6bps, or $300k, upfront to Moody’s in exchange for that rating. The WTP-price ratio is thus of the order of 50:1 (undiscounted). Look around you. How many companies save fifty dollars for their customers for every dollar they charge? Assuming prices are raised by 5%/year (Moody’s Investors Service raise them by ~3-4%/year), it would take some 80 years to squeeze all the value—something that’s hard to rock since the standards business will always tend toward a natural oligopoly. Better yet, a price hike at Moody’s isn’t commensurate with increased retention cost and capital investment, meaning that it flows directly to the bottom line and return on invested capital.

AutoZone is a different example since the value prop isn’t entirely grounded in savings to the customer although that’s an important part of the equation. By and large, AutoZone’s pricing power roots in its ability to deliver convenience. By owning the best locations in the industry with the largest footprint of stores across the US and focusing intensely on offering a gigantic SKU library with everything in stock at all times, AutoZone’s customers (75% private auto owners and 25% professional mechanics) know that they can trust AutoZone to be able to provide the level of service they need before heading to the store (if your car is broken down, it’s night and day whether you can get the necessary spare part right away or wait for weeks, which, by the way, is one of the reasons why physical auto parts retail has an advantage over e-commerce). Because demand continually exceeds supply from an ever-increasing car parc, customers will happily pay more and more for that convenience, and since convenience is the main competitive factor in the industry, pricings have always been rational. For the past 23 years, AutoZone hasn’t had a single year with negative revenue growth, a feat attributable to its constantly increasing prices that have lifted the gross margin from 42% to 52% over the period. In contrast to something like Moody’s Investors Service, where the WTP is somewhat fixed but the price charged decades away from it, AutoZone is an example where keeping the WTP-price ratio fixed, although it may not be wide (there’s little chance that AutoZone provides 50 dollars of value for every dollar they charge), can be equally as durable.

A large WTP-price ratio, of course, on the face of it represents just a snapshot, and while it is the strongest indicator of pricing power, it may not always be so. AutoZone has a strong corporate culture grounded in the inspirational mindset that the rational and equitable division of value is the only appropriate way of ensuring that its business will grow in strength as it grows in size. But a culture like AutoZone’s is rare. A wide WTP-price ratio has no way of ensuring that culture slippage will not occur, giving into the temptation to ‘harvest’ more value, especially if enough external pressure (from short-term investors and activists) is put on such a company to capture more value for itself. And not just at the expense of customers. In alignment with the Value Stick framework, if it’s true that maintaining a wide WTP-price ratio is the decisive factor behind a company’s pricing power, it’s also true that willingness to sell (WTS) plays an equally large role in the moat-building equation. For the vast majority of companies, their most important supplier are their employees, which means that instead of thinking of the difference between WTS and cost as ‘supplier surplus’, you can logically swap that with ’employee satisfaction’. In focusing too much on how much to charge, what many companies often overlook is they can lower their own cost while preserving value for their suppliers by lowering their WTS (a topic we’ll return to). Getting both sides of the Value Stick right in terms of value creation is an ideal form of a win-win-win situation.

Other times, and this is where counterintuition fits with the framework, paying your employees more (so that your costs go up, WTS stays unchanged, and more supplier surplus is created) can actually be beneficial to long-term shareholder value if it fits a strong culture that fosters intrinsic motivation. For example, Costco by some measures pays its lower-level employees upwards of 50% more than its competition, which has led to an >9-year average tenure of its US employees of which more than 12,000 have worked at Costco for 25 years or more—an unusual feat of loyalty in the retail business. James Sinegal, Costco’s founder and CEO until 2012, was notoriously frugal when it came to spending at headquarters and on C-suite pay. But it wasn’t about taking all the value for himself and his fellow shareholders. Instead, he plowed all of the savings from HQ frugality into paying average workers in the retailer’s stores and warehouses handsome hourly wages. Sinegal perfectly understood the value of a dedicated worker, meaning better customer service, higher sales, and lifelong club members when he said: “The more people make, the better lives they’re going to have, and the better consumers they’re going to be.”

In a 1998 university speech, Buffett presented the same idea related to See’s Candy, a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway:

If you are See’s Candy, you want to do everything in the world to make sure that the experience basically of giving that gift leads to a favorable reaction. It means what is in the box, it means the person who sells it to you, because all of our business is done when we are terribly busy. People come in during theose weeks before Chirstmas, Valentine’s Day and there are long lines. So at five o’clock in the afternoon some woman is selling someone the last box candy and that person has been waiting in line for maybe 20 or 30 customers. And if the salesperson smiles at that last customer, our moat has widened and if she snarls at ‘em, our moat has narrowed. We can’t see it, but it is going on everyday. But it is the key to it. It is the total part of the product delivery. It is having everything associated with it say, See’s Candy and something pleasant happening. That is what business is all about.

Expanding the Value Stick

As we established, pricing power is just as much about maintaining a spread between what you charge and what the customer is willing to pay as it is about maintaining a spread between what it costs to produce and what your suppliers are willing to sell it for. Generally, in the absence of coerciveness, the spreads at both ends of the stick indicate the durability of the company’s pricing power. Early in a company’s growth trajectory, it makes sense to reward customers and suppliers disproportionately since customer referrals and repeat business are so essential to the development of a valuable franchise. As a business matures, the value division can be changed around—too much, though, and the moat is drained for longevity. What can often cause good analysts to misanalyze reported profitability or a boost to the gross margin is exactly when it’s a function of harvesting, either by pressuring employees, cutting advertising expenses, and so forth. Worse, this often leads right to suffering a double whammy since, just as profitability goes up, the once highly-rated company enters a growth limbo, slowing just at the time when the analysts spot their misanalysis.

Since utilizing pricing power is about raising prices steadily and over time, a static spread does little for you (except when it’s exceptionally wide as in the case of Moody’s and S&P), so the more important trick is to figure out what the companies do right to widen both sides of the Value Stick. To preserve pricing power, any changes to the division of value without increasing value itself should be made for purely competitive reasons and not driven by a wish to pander to investors—at least those with a long-term view. Focusing on what a company does right to create more and more value for customers and suppliers is what helps you get to the core of its moat.

Ways to Increase WTP

The ways in which a company can increase a customer’s WTP can roughly be divided into two broad categories: love and utility (with coercion being the unsustainable third).

Love

“Love” is a fitting word to describe the phenomenon where customers are not only genuinely happy to do business with you but also root for your success. Now, you’re probably thinking why I wouldn’t substitute “love” for “brand name” instead, the reason being that love goes beyond brand name because a well-known brand name is not always value-creating, nor durable. Some of the largest consumer car brands or airlines are known all over the world—even kids can list many car brand names off the top of their heads—but few have historically delivered economic returns and even fewer have possessed anything close to pricing power.

So a well-known brand, in and of itself, isn’t a reliable source of value creation and pricing power. But it can be. The willingness to pay for a brand is high if you are in the habit of using it, have an emotional connection to it, trust it, or believe that it confers social status. When you have loving customers and you make a profit, they cheer, because they want you to thrive, which makes all the difference in the world. They advocate for you publicly, they tie their personal brand with yours, and they don’t even consider the competition. Technological edges can be lost and scale economies can be matched, but a loved brand name often endures the trials and tribulations of competitive fate.

Many factors play into how to create loving customers: they may enjoy supporting your mission or community, they may enjoy reciprocating exceptional service, they may fall in love with your design, quality, and reliability, they may love your corporate culture and how you treat your people, and/or they may feel part of a community or ecosystem, either a space where members learn, teach, and support each other or wherein all members make more money or gain more prestige than had they not been part of the group. A collective way to describe these parameters is that a valuable brand provides high-quality, low-variance outcomes. Continuously evading to disappoint the customer’s expectation is what builds trust. So continuing to increase the customer’s WTP is about improving trust through one or each of these parameters.

The most common way to build trust is by reducing search costs. The less research a customer has to do before making a purchase decision, the more their purchase decision leans on trust, and the less will be their acquisition cost (CAC). And, the more they find that the trust was warranted, the more the trust in the brand is reinforced. For consumer staples, the way to reduce search costs is via distribution scale. Coca-Cola and Anheuser-Busch InBev are excellent examples of that. Both are market leaders on a global scale in each of their categories and have built distribution networks that allow their brands to be at the forefront of pretty much every consumer’s mind—Coca-Cola in almost every country on the globe and Anheuser-Busch InBev in its select markets where their leading labels, which is different from country to country, have trounced competition for decades.

In the case of Anheuser-Busch InBev, the company has for years followed a ‘natural’ annual increase in WTP as an effect of premiumization, notably in developing markets as consumers experience increases in economic prosperity (while labels such as Bud Light and Budweiser are mainstream labels in the US, they’re perceived as premium labels in many developing countries). Precisely due to this premiumization effect, the alcohol industry is historically one that isn’t prone to price wars to grab market share, since consumers tend to pick an alcoholic label by taste memory, tradition, status, or patriotism, not price, which in turn properly explains why pretty much no retailer in history have gained any traction with lower-priced private label alcoholic beverage. Anheuser-Busch InBev’s management knows how to juggle when it’s time to increase the customer’s WTP and when it’s too early. Only once the company has achieved viable scale in a new market does it introduce its premium labels.

The same secular ‘natural’ trend of premiumization is evident in other companies with vast global distribution networks and footprints, such as Starbucks, which is as much synonymous with selling a lifestyle as it is with selling coffee—an exemplification of how WTP can be attributed not just product characteristics and prices, but also by an array of behavioral factors. It’s no wonder that some of the strongest brand names with the most pricing power are shrouded in mystery. If building brand value was simply about spending billions of dollars on advertising, the biggest spenders should top the list of the most valuable brand names but there are many who don’t show up. And although I did list some aforementioned parameters for increasing brand value, you could almost argue that getting each of these parameters right is as much a function of serendipity, almost luck, as it is about planning. Anyway, Starbucks nailed the design of creating a lifestyle habit that transcended it into a state where growth begets growth. Any time Starbucks opens a new coffee shop, hype makes sure the brand value is reinforced, the loyalty program grows, and pricing power is strengthened—a case in point being that Starbucks earns a two-year payback period for every new store it opens.

Utility

Increasing the WTP for a customer through utility requires that your product becomes increasingly useful to the customer, either monetarily or productively.

BEES, a B2B e-commerce platform that Anheuser-Busch InBev has developed over a 7-year period acts as the company’s window of sharing the enormous amounts of data gathered about consumer preferences across its markets—data that, for instance, helps restaurant and bar owners estimate demand in different categories and indicate price elasticity across the labels. Meanwhile, restaurant and bar owners can utilize BEES to keep track of their inventory and sales progression to derive when and where demand spikes for a particular label. It’s so helpful to restaurant and bar owners that 4/5 data recommendations play into their procurement process. By helping restaurant and bar owners succeed, the relationship strengthens, and the Value Stick widens.

A product that’s well-integrated into the customer’s workflow and business without comprising an uncomfortable level of the customer’s total cost base is another great example of expanding WTP through utility since, as the customer grows, the product, assuming that it’s mission-critical, becomes increasingly valuable and WTP goes up. By dominating a critical niche within software solutions to the asset management industry, SimCorp with its market-leading solution SimCorp Dimension is so entrenched and valuable to its customers’ daily operations that the switching costs of going with another vendor make the very thought of it bad business. SimCorp continuously invests in expanding the customer’s WTP through R&D spend that adds new and desired functionality. The more complex SimCorp’s solutions become, the more employee training is required for the customers, and the more familiarity matters to the daily workflow.

If it isn’t already evident from the discussion above, it’s important to mention how network effects can play into increasing WTP in both ‘love’ and ‘utility’ (as well as ‘coercion’). Once a particular network becomes dominant, it shifts the demand curve up and increases WTP. In ‘love’, network effects spur increases in WTP when a particular brand is enforced by communities. In ‘utility’, network effects are most evident when the utility of a product or service functions as a two-sided network. Experian provides such a network. As the world’s largest data services provider, Experian excels in the dissemination of data and analysis. Experian’s huge databases contain payment data, credit history, data from public registers, auto information, and other data, provided via mutual cooperation with its own customers. Particularly in the US, Experian benefits greatly from mutual cooperation with the largest banks, which gives Experian access to vast amounts of data that competitors cannot compete with unless they build similar relationships. As more lenders and businesses contribute data to Experian’s network, the value of the information and the accuracy of credit reports increase. A way to think about WTP is what it would cost the customer to cover their needs themselves. In the case of the kind of data Experian possesses, those ‘replacement costs’ could run into several million. Since Experian’s huge scale of proprietary data requires approximately zero marginal costs to maintain, the company can produce and deliver at a fraction of the value its services create for customers.

Ways to Decrease WTS

What companies often overlook is the option to create more value and thus increase its pricing power by not only boosting the customer’s WTP but also lowering their supplier’s WTS. When a company can lower its own cost by reducing the supplier’s WTS by the same factor, the situation of reducing costs goes from being zero-sum to win-win.

One way of reducing WTS is through data. In the digital age, leading businesses gather substantial amounts of data about their customers, their preferences, and, most importantly, their habits. Sharing this information with the supplier can lower their WTS. Suppose a supplier currently earns a NOPAT margin of 10 percent and has a capital turnover of 1.5x, resulting in a return on invested capital (ROIC) of 15 percent (10% x 1.5 = 15.0%). Now, let’s imagine that its customer gives it proprietary data that helps the supplier reduce its invested capital, thereby increasing its capital turnover to 2.5x. As a result, the supplier could potentially reduce its product price to achieve a 6% NOPAT margin while still earning a 15% ROIC (6% x 2.5 = 15.0%). Moreover, the supplier has the option to lower the price even further to an 8 percent margin, creating value for the firm and additional surplus for the supplier.

A more easily available way to reduce your supplier’s WTS is through productivity. Obviously, economies of scale matter a whole lot in that equation. Economies of scope matter too. To even come close to matching AutoZone’s breadth and level of stock availability, a competitor would need to match AutoZone’s vast and historic investments in its distribution network and other systems involving 12 distribution centers and ~80 mega hubs, a huge supply chain orchestra that allows its smaller stores (which, with its average SKU-level of 25k are not really small) to offer a larger inventory with fast delivery in addition to direct delivery to mechanics.

The thing about economies of scale and market-leading positions, certainly as it relate to retail chain stores, is that it brings huge purchasing power. AutoZone’s scale allows them to negotiate favorable supplier terms. Its 126% accounts payable to inventory (which increases year over year) means it essentially has suppliers finance their working capital. In other words, only when AutoZone has sold to the customer and received payment does the supplier get paid. This operating efficiency allows AutoZone to achieve mighty returns on capital and means that AutoZone can raise prices to customers before inflationary impacts from input costs, ensuring a period of increased earnings when inflation goes up.

And purchasing power is not only useful in pressuring a supplier’s WTS. There are several second-order benefits as well as it relates to bringing costs down without it being at the expense of the supplier relationship. For one, there’s specialization. The larger your retail footprint, there more experiments you can conduct. If a small, single-store operator is trying to buy across 30 different merchandise categories influenced by traveling salesmen, they’re going to make a lot of dumb decisions. But if the procurement is done at headquarters for a large number of stores at the same, the store experiments can be utilized to make expert decisions within each category.

Pricing power is one of the sole reasons for durable value creation and when you find a company that possesses it in the true sense of the term, it’s about sitting tight and letting the intrinsic value come to you, slowly and over time. Thinking about a company’s pricing power in terms of value, not price or costs, on both sides of the Value Stick is the surefire way to identify it. If there’s an overarching lesson to take away from the discussion, it’s this: many of the companies that have pricing power in its most durable form may also be the ones under-earning the most compared to their potential. This opens up extraordinary long-term investment opportunities for those that are willing to look beyond reported earnings.