In 1917, an American grocer named Clarence Saunders was the first to patent the concept of the self-service grocery store and thus singlehandedly founded the modern version of the discount supermarket.

One would think that the first discount supermarket today would be a globally known name and among the most prosperous chains in the United States. But although it still operates today, chances are you’ve never heard the name of Saunders’s supermarket chain unless you live in the southern or midwestern United States. Its name is Piggly Wiggly.

The truth is that Saunders and Piggly Wiggly did have great chances of accomplishing what Sam Walton later did with Walmart. But the reason why it didn’t end up that way wasn’t directly related to its business. It was related to the company’s stock.

After opening his first Piggly Wiggly store, Saunders was fast to expand the business into many states through direct ownerships and franchises with continuous success. But as 1922 passed, some of the stores operated by franchises in New York ran into financial trouble and closed their operations. As a result, some investors tried to take advantage of this by starting a bear raid against the company on the New York Stock Exchange by aggressively shorting the stock. The stock price dropped so fast that it began a chain of concerns among the company’s existing investors and creditors.

Eager to teach these short-sellers a lesson, Saunders decided that he wanted to corner the market by acquiring all the shares that were being traded and lent to short-sellers. Once Saunders would own enough of the shares outstanding, he would be the ultimate lender and subsequently issue a notice demanding the shares redeemed at a high asking price.

So by borrowing ten million dollars from banks, Saunders managed to accumulate 98% of the shares traded and drive the stock price up from $39 to $124 in a short period; a catastrophe for the bear raiders who faced enormous losses when the price ascended.

But just as Saunders’s plan seemed to work to the tee, the bear raiders managed to convince the stock exchange to intervene and suspend trading in Piggly Wiggly and later grant an extension for paying up. This gave enough time for the short-sellers to access shares of Piggly Wiggly not in circulation and thus forcing Saunders to offer his shares at a steep discount.

Saunders’s position was not tenable due to his debts, and he eventually suffered so large losses that he was forced to declare bankruptcy. The corner was successful, but the man who executed it eventually went broke. Saunders failed to grasp the second-order effects of acting on his principle.

The story of Clarence Saunders and Piggly Wiggly is brilliantly described at length in John Brooks’s 1969 book, Business Adventures (chapter: The Last Great Corner).

***

Other than the Piggly Wiggly story, history has managed to throw up other incidents of these dramatic market corners – some equally unsuccessful and others rather fruitful for the initiators.

Cornelius Vanderbilt famously managed to pull off a corner in 1862 of the Harlem Railroad by anticipating its strategic value in the midst of a bear raid. The move not only made him a small fortune but also gained him control of the only two rail lines offering service to Manhattan.

“I don’t care half so much about making money as I do about making my point, and coming out ahead”

Cornelius Vanderbilt

At the time, the raiders selling short the stock of Harlem Railroad were not your ordinary investors. They included members of the New York City council as well as directors of the board at the company itself. The raiders tried to profit by shorting a railroad company that Vanderbilt controlled and then revoking the company’s principal asset: a license to operate a street railway. One of those board members was a long-time Vanderbilt rival and legendary speculator, Daniel Drew.

At last, when Vanderbilt owned more shares than there were outstanding, he offered to let the council members cover their short positions with only small losses if they recalled the license. Which they did. The biggest loser in the corner was Daniel Drew.

The Vanderbilt story was described by Edwin Lefevre (alias of the legendary speculator, Jesse Livermore) in Reminiscences of a Stock Operator. He wrote the following about the corners in the 19th century:

A wise old broker told me that all the big operators of the 60s and 70s had one ambition, and that was to work a corner. In many cases, this was the offspring of vanity; in others, of the desire for revenge. […] It was more than the prospective money profit that prompted the engineers of corners to do their damnedest. It was the vanity complex asserting itself among cold-bloodiest operators.

A more recent story involves the Hunt brothers, Nelson Bunker Hunt and William Herbert Hunt, who in the 1970s and 1980s attempted to corner the global silver market and at one point held the rights to more than half of the world’s deliverable silver. The price per ounce climbed from $11 to almost $50 over the course of 4 months, but due to changes made to exchange rules regarding the purchase of commodities on margin, the price crashed below $11 only two months later. The Hunt brothers went broke.

***

Today, market corners have evolved to become a rarer sight since they are now illegal in most countries and the lessons of history have made participators more wary of attempting to create them.

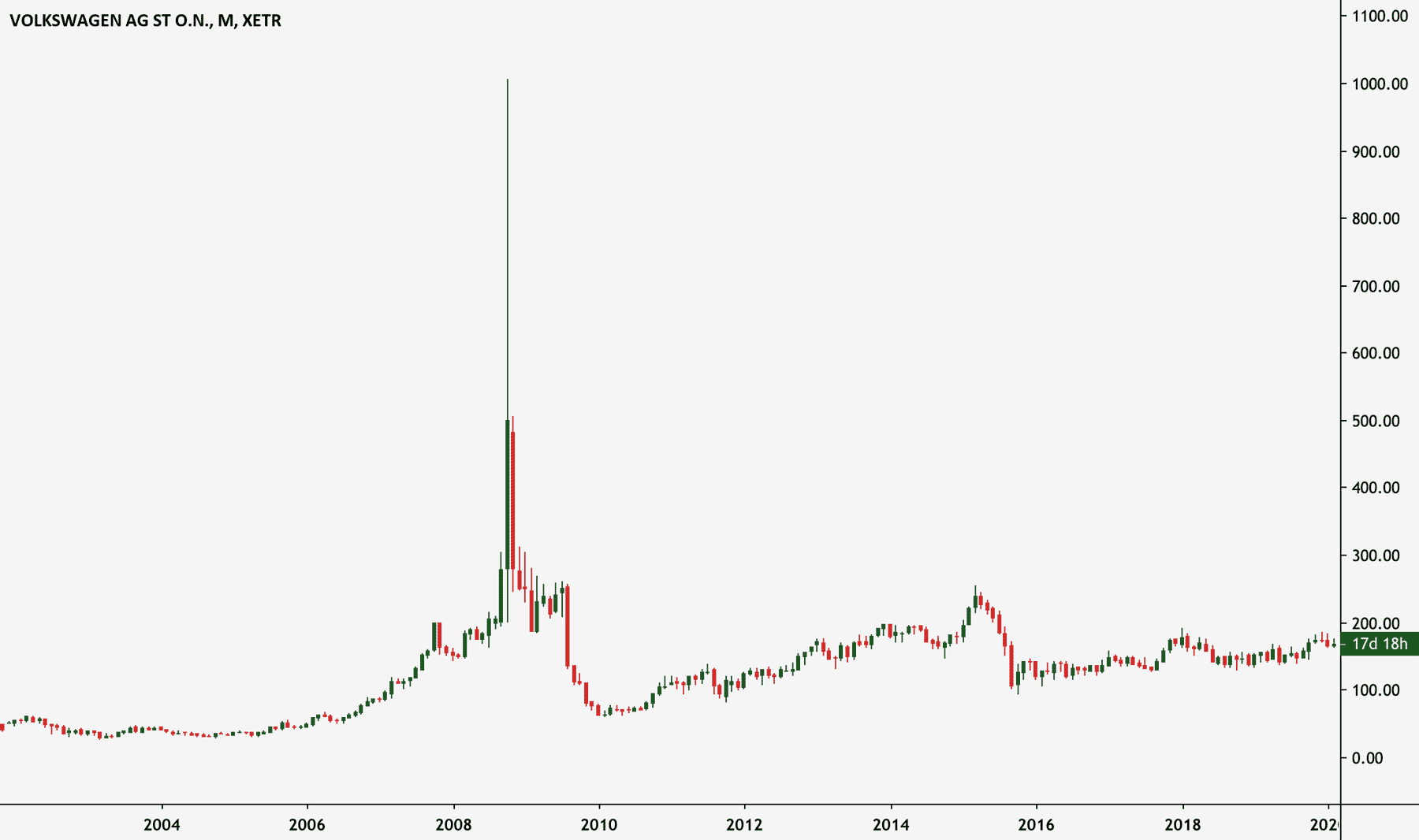

But one of the most fascinating cases in recent times happened not so long ago. One that essentially reinvented the way to conduct market takeover attempts by circumventing the transparency and disclosure of market operations, and regulations, using a new derivative invention. The result of the event created an enormous short squeeze in the stock price of the company given which for one brief day turned the company into the world’s largest.

It looked like this:

The history of Germany’s most famous carmakers, Volkswagen and Porsche, goes back to 1931. After Porsche’s transformation from a consulting firm to a carmaker, the two companies collaborated for a long time with Porsche outsourcing much of its manufacturing to Volkswagen.

In 1993, Volkswagen was in financial trouble and the man to the rescue turned out to be Ferdinand Piëch, Ferdinand Porsche’s grandson, who was instated as chief executive and chairman of the board.

While reigning, Piëch and his wider family still retained 50% voting right control of Porsche with the other half held by the Porsche side. The rivalry between the two carmakers intensified, and together with a mix of personal family disputes, the new business relationship formed the setting for Wendelin Wiedeking, the leader of Porsche, wanting to decadently take over Volkswagen through the open market.

While being open to the public about the takeover attempt, Wiedeking quickly gained a 20% stake of Volkswagen and increased it to 30% over a couple of years. In the meantime, the doorstop meant to keep Porsche and other unfriendly takeovers away, the Volkswagen Act, was overturned by the European Commission. The Volkswagen Act originally required a party to own at least 80% of voting shares to gain control, but the overturn now only required the 75% standard requirement. As the state of Lower Saxony owned 20.1%, Porsche now had a formal chance to cross that threshold.

As soon as Porsche’s stake reached 35%, Wiedeking stopped scooping up shares. Or so it seemed.

In Germany, there’s a long tradition of dual share classes in publicly traded companies frequently consisting of preference shares that hold no voting rights (but a fixed dividend) and ordinary shares held by controlling insiders.

As Wiedeking’s plan was open to the public, short-sellers and hedge funds soon discovered that Volkswagen’s preferred shares were trading at a significant discount to the ordinaries nearing almost 70%. While the price of the ordinaries climbed voraciously, the preferreds stayed put.

Perplexed by the large capital structure divergence since Wiedeking hadn’t disclosed buying any more shares, one analyst suggested that Porsche might use cash-settled options to accumulate its stake without public disclosure. Other analysts labeled that thesis illusory, and a pile of hedge funds started going short the stock and long the preferred to profit on the huge divergence.

Since the market had just reacted to the biggest financial crisis since the 1930s after the fall of Lehman Brothers, the short-sellers of Volkswagen seemed nicely positioned. But the price of the ordinaries kept climbing and the capital structure spread soon widened to a mind-boggling 80%.

A press release now hit the terminals, and Porsche announced that they had accumulated 74.1% of the ordinaries outstanding using cash-settled options – just as the analyst predicted. Since 20.1% was already owned by the state of lower Saxony, it was mathematically impossible for every short-seller to cover their positions since 12% of the shares outstanding were now sold short.

The massive squeeze out the exit door fueled the stock price to a high of €999, briefly making Volkswagen the largest company in the world until the price went all the way down again by December 2018. Hedge funds lost an estimated $20 billion.

But it wasn’t a happy ending for Porsche either.

Porsche was short of the cash required to take delivery of the shares it had committed to buy via the options to pass the 75% ownership mark. Through the process, Porsche had taken on a €15 billion debt with €10 billion was coming due in under 6 months just as global car sales were plummeting. Porsche luckily diverted bankruptcy by ironically being bailed out by Volkswagen who later acquired the remaining half of Porsche for $4.5 billion – To Ferdinand Piëch’s delight.

***

Often due to questions of transparency, the phenomenon of short squeezes most frequently occurs in small-cap markets – more specifically with penny stocks. Like when the most hated man in America, Martin Skhreli, orchestrated a violent short squeeze on the failed biotech company, KaloBios. KaloBios’s only real drug had just flopped and the company had insufficient cash to pay over $6 million in debt. Short-sellers perceived the short as a “no brainer near term zero”. But when Skhreli announced that he with a group of associates had acquired over 50% of the shares outstanding and that he wouldn’t lend any more stock to those looking to short it, its stock rose by an overwhelming 10,000% in just five trading days.

But large short squeezes, like the Volkswagen or KaloBios stories, do not necessarily originate from a market corner or takeover attempt. The vast majority of short squeezes simply happen in situations where a signification part of a company’s float is shorted by a group of short-sellers who have a very different view of the company compared to the market. And when something happens that forces short-sellers to debunk that view, the exit door is sometimes smaller than needed at the given time.

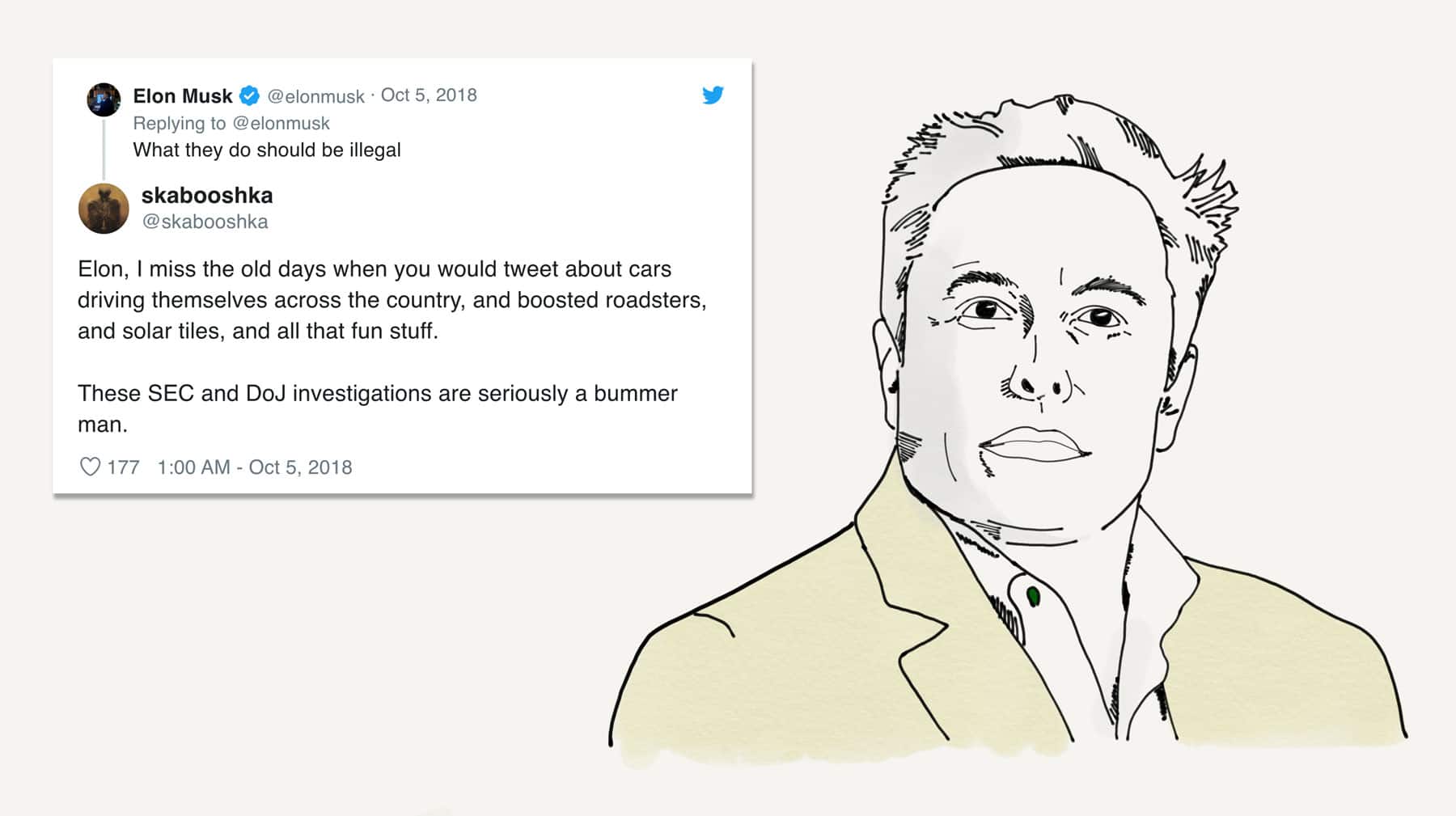

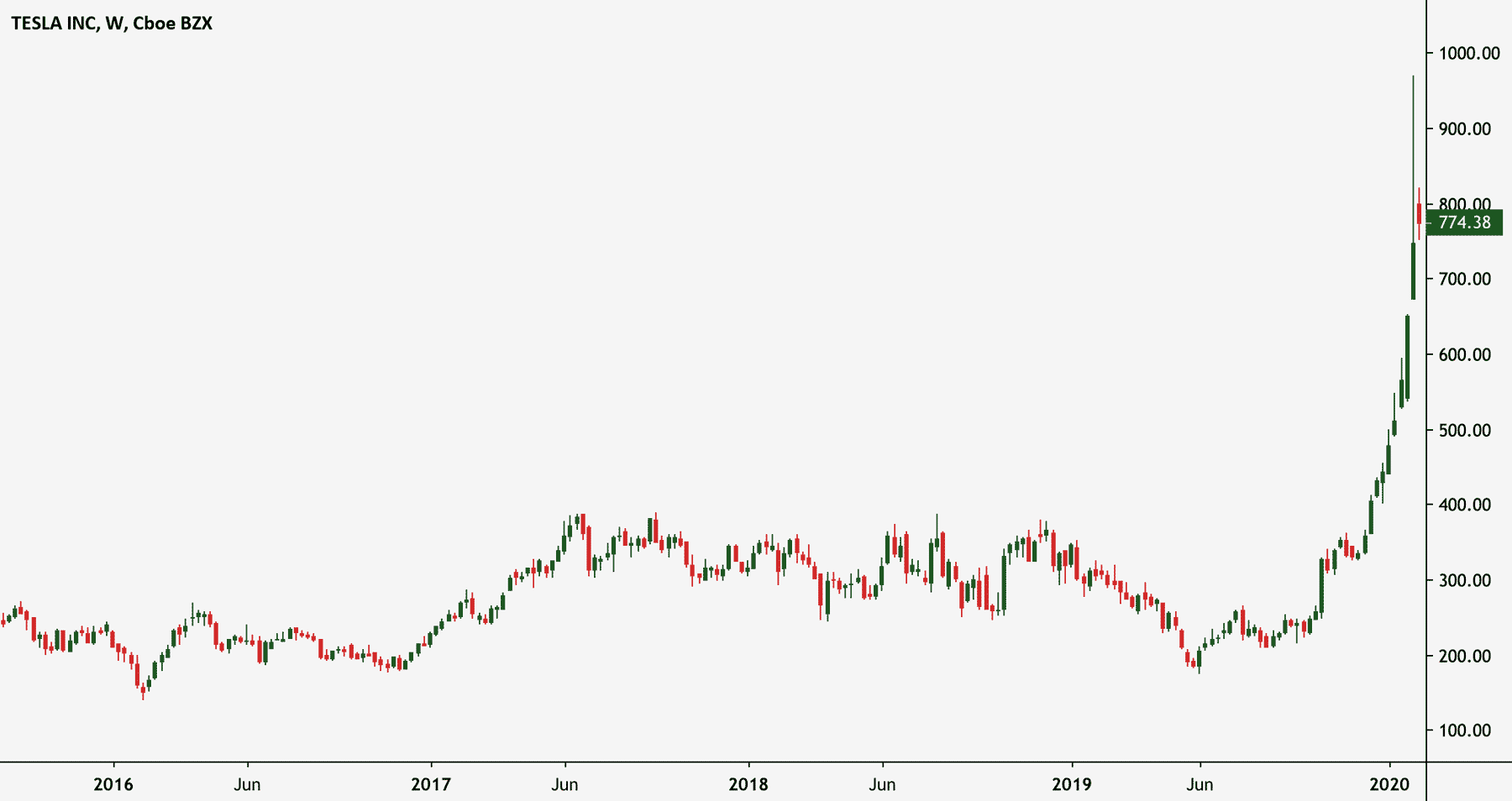

The obvious recent case is what multiple media outlets call the “Tesla mania”. For years, it’s been in fashion to either love or to hate Tesla and Elon Musk’s leadership style, and the stock has thus been heavily shorted ever since the beginning of 2011 of which the percentage of the company’s float shorted has fluctuated between 20% and 35% since 2015.

The prospects of Tesla’s business and the tug-of-war between bulls and bears, including prominent fund managers like David Einhorn and Mark Spiegel (who are still convinced that the company is a house of cards ready to collapse), have over the years created a rather volatile stock price.

As Ihor Dusaniwsky, Head of Predictive Analytics at S3 Partners, has put it:

“It’s not just a financial transaction – it’s almost a lifestyle choice to be on one side or the other. […] There are cultish convictions on both sides. It’s almost as a college football game – people are just crazy fans and it doesn’t matter what the team does.”

Obviously, as previous cases in this article have exemplified, companies and their CEOs are commonly not fond of short-sellers and the resulting uncertainty around their company’s stock price. Especially so for Elon Musk, since Tesla’s future prospects are still highly dependent on their ability to raise capital in the market to fund operations and growth, and downward pressure on the stock price threatens that ability and, ceteris paribus, increases borrowing costs.

Tesla has historically been fond of issuing convertible debt to finance operations. Thus, whether the company has been able to pay off that debt in either cash or equity has been very dependent on the level of the stock price.

So, Elon Musk started publicly stating his no-filter opinion on short-sellers and their motivation to find and spread negative sentiment about Tesla (what others perceive as highlighting real issues with the company). As he got worked up by the short-sellers’ persistence, it turned into Twitter rampages late at night, public feuds with hedge funds managers, and lashing out against critics. Many remember the threat to take Tesla private, social media posts that attracted the scrutiny of the SEC and alleging the existence of saboteurs within the company. All actions that made Elon Musk look increasingly less like traditional CEO leadership material.

So much that even loyal Tesla fans started to wonder about his actions.

As history showed with the company’s namesake, Nikola Tesla, inventive genius and eccentric behavior sometimes go together.

The spectacle around the “taking Tesla private” case seemed to work out for the short-sellers as the stock price dropped about 50% from November 2018 to May 2019. But then, amidst Tesla’s opening of the Shanghai Gigafactory (“Giga Shanghai”) and the announcement of the company’s first annual operating profit topping analyst projections, tables turned and the brow-beaten Tesla stock skyrocketed as previously steady short-sellers started getting anxious and scrambled to cover their positions. And on top of that, Tesla fans, who weren’t already heavily invested in the company, started to feel the FOMO effect and began adding extra fuel (or electric power) on the way up.

We have yet to see the ending to the Tesla story but one thing is certain: it never acts out as one expects and it might go much further. According to S3 Partners, short positions on Tesla shares have in the last seven months lost $8.4 billion.

***

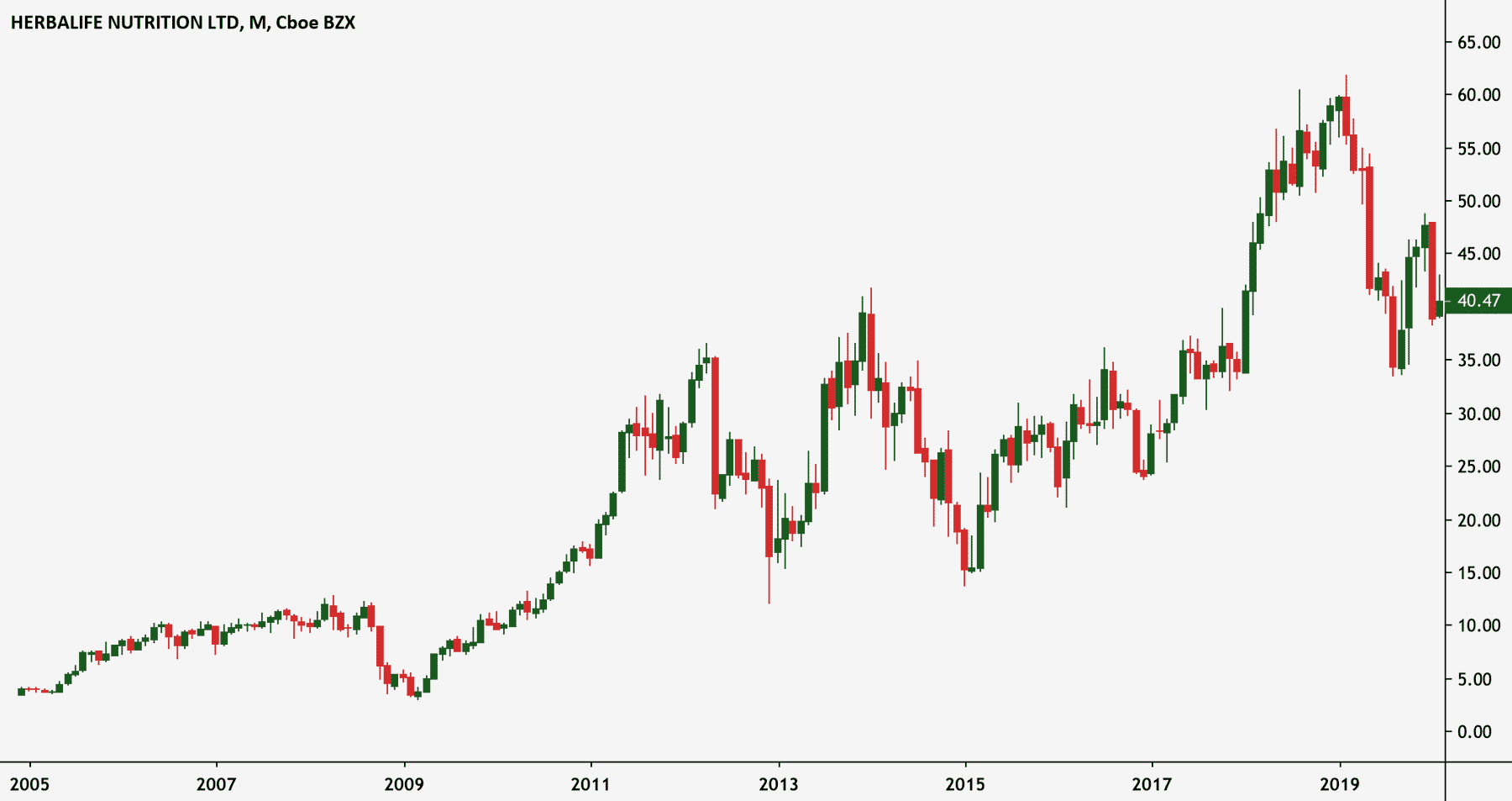

Another case of tug-of-war between prominent fund managers and a debatable business model was that of Bill Ackman, the fund manager behind Pershing Square, and his $1 billion dollar bet against Herbalife initiated in December 2012.

But the main difference from the Tesla case was arguably more agonizing for the short-sellers. Herbalife was a continuous short squeeze happening over a stretched time period of many years.

When Ackman took his position in 2012, he spelled out his short thesis on Herbalife in a three-hour presentation at an investment conference (documented in the Netflix documentary, Betting on Zero) calling the nutritional supplements company a pyramid scheme destined to go to zero.

One of the slides at the presentation stated:

“Participants in the Herbalife scheme, the distributors, obtain their monetary benefits primarily from recruitment rather than the sale of goods and services to consumer. […] Herbalife inflates the suggested retail price (SRP) of its products and overstates ‘Retail Sales’ in its public filings to conceal the fact that Recruitment Rewards earned by distributors are substantially greater than the Retail Profit they generate.”

Although I personally think he is right about the viability of Herbalife, Ackman’s real problem was that the other side of the trade had prominent investor, Carl Icahn, who took a long position and acquired 26.2% of the company. The two grand investors started an intense feud in the media.

Subsequently, over the course of the next five years, Herbalife managed to report improvements in its financial position by showing growth in both revenues and cash flow generation. The Federal Trade Commission fined the company $200 million after investigating its practices but never officially labeled the business a pyramid scheme.

The stock kept surging and Ackman lastly exited his position in February 2018. Although Pershing Square’s loss is unknown, it’s estimated to be close to the full $1 billion bet. Ironically, Icahn profited about the same amount.

Conclusion

There is a lot to learn from business history through the Piggly Wiggly market corner, Vanderbilt’s control of the main railroads into Manhattan, the Hunt Brothers bankruptcy, the Volkswagen short-squeeze, the current Tesla mania, and Ackman’s fight against Herbalife.

How businesses prosper or dissolve is as much about the strengths, weaknesses, and behavior of the leaders of that business in challenging circumstances as it is about the particulars of one business or another. The stock market, like businesses, is about human behavior and everything that it brings, whether its high integrity or destructive biases within individuals and crowds.

Leaders who focus on the development of their businesses are far better equipped to achieve a prosperous long-term future than leaders who sacrifice that opportunity by putting all their energy into focusing on their stock. When companies turn into raids and promotions, it’s better to learn some things about human nature from the sidelines.

Ending remark: Stay clear of shorting even outright scams. I once experimented with shorting pump-and-dump situations and short squeezes in the small-cap space and it was a non-enriching experience. When price detaches from fundamentals and the course is up to erratic human behavior, you never know how long or how far such things can last. Even though you might know where it eventually ends up.