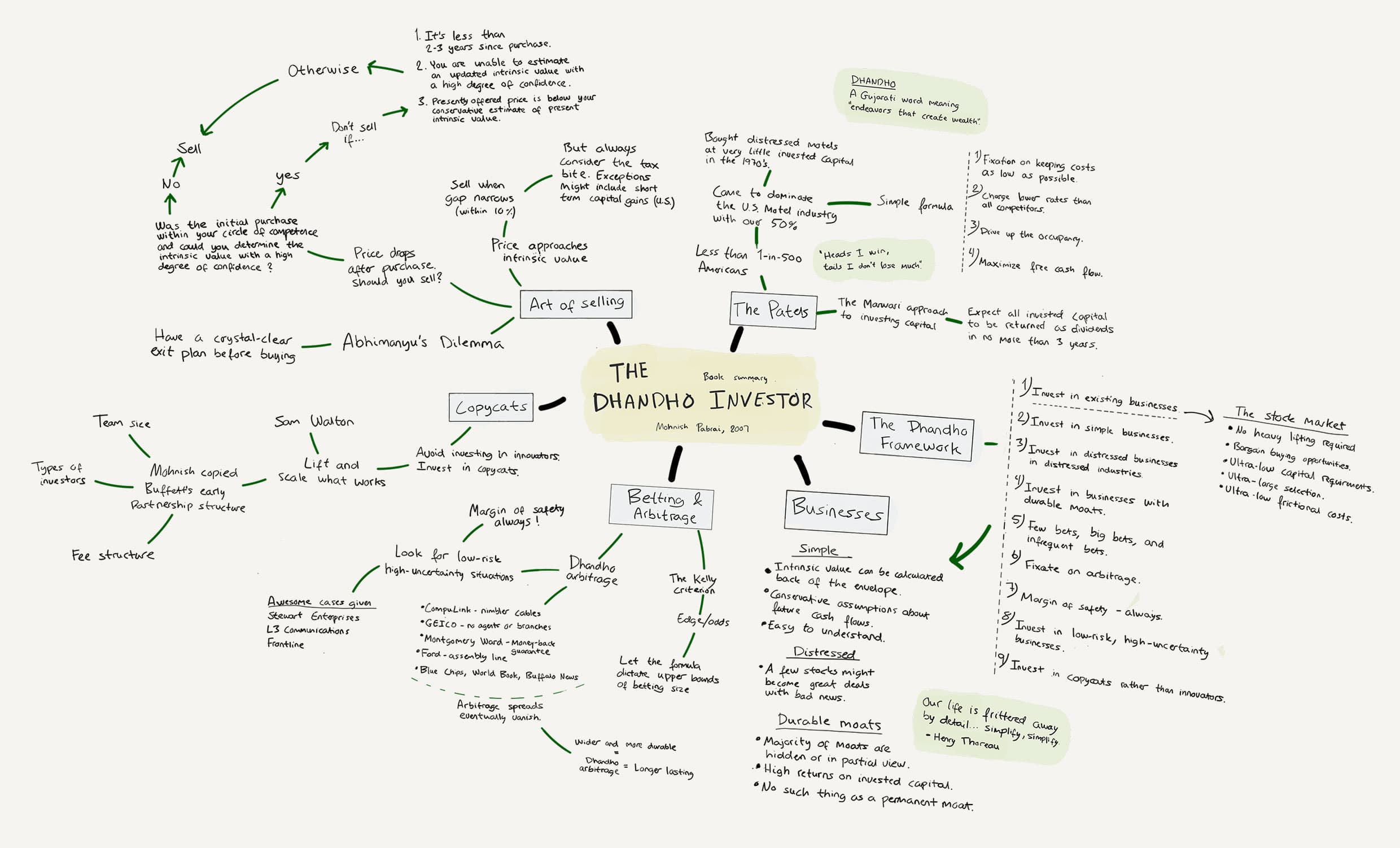

In the 1970s, a small ethnic group from India named the Patels first began arriving in the United States as poorly educated people with no money to their name. Today, this small sub-part of Indians makes up only about 0.1% of the U.S. population but has ended up owning well over 50% of all U.S. motel assets worth well over $50 billion.

And after conquering motels, The Patels went upmarket and started trumping high-end hotels such as the Marriotts, the Hyatts, and the Hiltons applying the same principles which allowed them to gobble up a dominating position in the motel business.

How was this possible?

The answer is that they simply outcompeted everyone using the principles of what author Mohnish Pabrai calls “Dhandho”; a low-risk, high-return approach to business stemming from the Gujarati word meaning endeavors that create wealth.

The Dhandho way of doing business is the pillar behind Mohnish’s own investing approach at Pabrai Investment Funds, and in The Dhandho Investor, he wonderfully distills the framework for how the Dhandho principles can be applied successfully in the stock market.

We’ll get back to the Patels and the Dhandho investor framework later in this summary. But first, In case you don’t know Mohnish Pabrai, here’s a short introduction of him:

In 1991, Mohnish started an IT consulting and systems integration company, TransTech, Inc. with $100,000 including $70,000 in credit card debt. 9 years later, he sold the company for several million dollars. The year before selling, he started Pabrai Funds following the same principles and structure (no management fee) behind Warren Buffett’s early partnership from 1956-1968. Since then, he has knocked it out of the park. Starting with $1 million in capital backed by 8 families at inception and a firm value investing approach, the Pabrai Funds has since achieved an annual return of about 13.3% after fees compared to the S&P 500’s 6% return as of the end of June 2019. Today, Pabrai Funds manage over $500 million.

At Pabrai Funds, there are no armies of investment managers and analysts. The fund and every investment decision are solely managed by Mohnish. He decides very meticulously how to conduct his day, who to cultivate relationships with, and what to read and think about independently.

In 2005, Mohnish came to the conclusion that poverty is driven by lack of education. So he and his wife founded the Dakshana Foundation; a non-profit operating with the same principles that made him a wildly successful value investor, using checklists and simple metrics to help educate Indians living in slums.

I’ve been a big admirer of Mohnish for years. Not only for his incredible achievements as an investor, businessman, and philanthropist but largely due to his uncommonly successful approach to how he lives his life and conducts relationships. He’s a master at enjoying life to its fullest and is one of the main reasons why I myself decided to avoid a long-term career in the conventional financial industry to start my own businesses and read, write, think, and invest independently. I recently quit my job as portfolio manager to pursue this kind of life.

This is the second time I finished reading The Dhandho Investor. It will not be the last time.

Here are my personal notes on topics from the book followed by the key takeaways:

The Way of the Dhandho Investor

Now, back to the Patels.

So how did they manage to dominate the U.S. motel industry starting with no capital and education?

In the early 1970s, the U.S. economy got hit by the Arab oil embargo, and the motel sector got hit especially hard, directly affected by the availability of disposable income and sky-high gas prices. At the time, many motels were selling at distressed prices, in some cases by banks that had foreclosed on them. No one wanted to buy a motel.

These depressed prices encouraged the decision for poor, newly arrived Patels to acquire distressed motels with limited invested capital. The family would live at the motel, thus eliminating any rent expenses. And since they would live and work in the same place, there’s was no need for a car. Everyone in the family could work doing all the cleaning, maintenance, and management.

To the Patels, this investment was a no-lose situation. If the motel went broke, they could simply work for several months to save up capital to make the bet once again because the capital investment was so low, and since the Patels didn’t have any money to their name, the personal guarantee to the financing bank was meaningless. If it worked out, the rewards were potentially huge… which they were.

The Patels succeeded so mightily in the motel business by gaining an unbreakable competitive advantage through a simple formula:

- Cost control: They fixated on keeping costs as low as possible through an intensity as forceful as zero-based budgeting. Since the Patels’ competitors wouldn’t be able to compete with the Patels’ way of living to drive costs lower and lower, they became the ultimate low-cost participant in the industry.

- Lower rates: The intense cost control allowed the Patels to charge much lower rates while remaining immensely profitable.

- Increase of occupancy: Lower prices meant increased occupancy and thus increased efficiency in operations.

- Free Cash Flow Maximization: The Patels were then able to maximize free cash flow and keep handing over motels to up-and-coming Patel relatives to run while adding more and more properties.

The snowball effect soon ended up in what became amazing statistics. So after the Patels cornered the motel market, they soon began expanding into higher-end hotels and other business models such as Dunkin’ Donuts franchises, convenience stores, etc.

The Patels took a riskless bet with huge reward potential on invested capital and kept making the same bet over and over again. They patiently waited for the right deals to materialize and bet big when they did. This is what became the philosophy behind Mohnish Pabrai’s “The Dhandho Investor”. Written with the intelligent individual investor in mind, Mohnish then presents how the Dhandho investor philosophy can be applied successfully to the stock market through the book’s two mottos:

“Heads I win, tails I don’t lose much!”

“Few Bets, Big Bets, Infrequent Bets.”

To lots of people participating in the stock market, these mottos sound foreign since conventional investment practice has always preached that to achieve a higher rate of return, one must settle for a higher level of risk.

Mohnish shows us that with Dhandho and value investing that this is not the case as long as investors stick to the right principles of:

- Investing in existing businesses; of which the stock market is the best option.

- Investing in simple businesses; where intrinsic value can be calculated “back-of-the-envelope” using conservative assumptions about future cash flows.

- Investing in distressed businesses; where a few fundamentally great stocks might become great deals on bad news.

- Investing in businesses with durable moats; earning high returns on invested capital keeping in mind that the majority of moats are hidden or in partial view and that there’s is no such thing as a permanent moat.

Mohnish goes through the characteristics of businesses meeting these criteria and introduces examples of his thought process through specific company case studies. He even spends time showing the reader where to find them, what resources to use, and the simple calculations used to value them. He does everything short of giving the reader his latest investment picks. But it’s up to the reader to find them when putting the book down.

Look for Dhandho Investor Arbitrage

In parallel to traditional arbitrage methods, including correlated and merger arbitrage, Mohnish introduces the Dhandho arbitrage; a situation that allows businesses to earn above-normal profits for a limited time before competitors or substitutes enter and destroy these higher returns.

He then goes on to introduce several great examples of businesses where the Dhandho investor arbitrage spread lasted only a few months, while others spanned decades. A short-lived arbitrage spread allowed the cable company, CompuLink, to tap into the distribution chain by at all times being one step ahead of their slower-moving, bigger competitors via constantly introducing nimbler cables to vendors until competitors got to catch up with the innovation. A longer-lived example included that of GEICO who reaped a Dhandho arbitrage spread by being first at selling cost-effective all insurance policies using inbound call centers and the internet, giving it a dominating position in auto insurance still maintained today after competitors narrowed the arbitrage spread.

Pabrai states that, due to brutal capitalism, all Dhandho arbitrage situations will eventually be eroded, but two important factors can allow investors to earn excellent returns in the interim: the size of the spread (or moat), and its duration.

Great examples also included that of three investments made by Berkshire Hathaway: Blue Chimp Stamps, World Book, and The Buffalo News. The moats of these businesses have all pretty much evaporated. But as Pabrai states:

This does not mean these were bad investments. On the contrary, all three have been home runs for Berkshire. They had very robust business models for enough years for Berkshire to generate a spectacular return on its investment. See’s Candy was partially bought from the float dollars at Blue Chip Stamps.

Look for Low-Risk, High-Uncertainty Situations

A central theme of the book is the notion that the market often confuses the distinction between high uncertainty and high risk. But these are exactly the kinds of situations where the market tends to discount businesses below intrinsic value, and where value investors can come in and reap sizable rewards. This was my favorite part of the book. Mohnish uses three brilliantly detailed examples of investments made in the Pabrai Funds where he took advantage of low-risk, high-uncertainty situations to earn spectacular returns, often in a relatively short time.

Whether its over-leverage as in the case of Stewart Enterprises, negative industry outlook as in the case of Level 3 Communications, or depressed shipping prices as in the case of Frontline, Mohnish walks the reader through three different miscalculations the market can make when assessing the risk of uncertain circumstances.

When extreme fear sets in, there is likely to be irrational behavior. In that situation, the stock market resembles a theater that is filled to capacity. Someone sees some smoke and yells “Fire, Fire!” There is a mad rush for the exits. In the theater called the stock market, you can only exit if someone else buys your seat – each share has to be held by someone! If there is a mass rush to leave the burning theater, what price do you think these seats would go for? The trick is to only buy seats in those theaters where there is a mass exodus well on its way to being put out. Read voraciously and wait patiently, and from time to time these amazing bets will present themselves.

The low-risk, high-uncertainty part of the book reminded a lot about Graham and Dodd’s wonderful case studies as laid forth in the classic Security Analysis. You learn something new every time to reread it just to pound the lessons in. Just great.

Look for Copycats, Not Innovators

Like with the Patels, Mohnish argues that in seeking to make investments in the public stock market, one should ignore the innovators and invest in the copycats run by people who have demonstrated their ability to repeatedly lift and scale.

He mentions Ray Kroc, who purchased McDonald’s from a pair of brothers and basically lifted and scaled the existing concept massively through the franchise model. Sam Walton at Walmart was a lifelong, expert copycat of what worked at his competitors and ended up outperforming everyone. And Microsoft took the idea of the computer mouse and graphical user interface (GUI) from Apple, Excel from Lotus, Word from Word Perfect, networking from Novell, etc. In each case, these savvy entrepreneurs took a demonstratively successful idea, improved on it, and scaled it hugely.

The Dhandho way is to invest in a proven idea and run with it.

Mastering the Art of Selling

Now, this is a real gem. Mohnish argues that to become a great investor, one needs a robust framework for both buying and selling and that buying is the easy part of the equation. How true that is!

Selling an investment is much more prone to human irrational behavior in taking a correct decision due to the commitment bias of owning that investment. Seasoned investors have all experienced exactly this problem by either falling in love with a stock or hanging on with a nagging hope.

Abhimanyu’s Dilemma

Mohnish likens the act of entering a stock to the Indian story of Abhimanyu’s Dilemma 2,500 years ago about two large families at war with each other. The two families were in a huge battle involving thousands of troops, swords, and elephants. One of the sides arranged their troops in a spiral formation, a Chakravyuha, which is designed like an Archimedes Spiral wreaking havoc on the opposing army and inflicting staggering losses. The story of the Chakravyuha was that if one could successfully enter all the way to its center, and successfully exit, it would lead to mass panic and disarray at the enemy’s leadership. But such a traversal would be virtually impossible.

Lord Krishna’s sister was the mother of the story’s hero, Abhimanyu. When Abhimanyu was in her womb, Lord Krishna was explaining to her how one enters a Chakravyuha and decimates it. She listened carefully to the first part of the story but fell asleep in the second part about exiting the Chakravyuha, so her unborn baby only heard half the story (2,000 years ago, they assumed that unborn children could listen to you). Abhimanyu goes into the Chakravyuha, has great success slaying enemy warriors and gets to the center of it, but he doesn’t know how to get out. In the end, he’s killed.

Every time one enters an investment, the story of Abhimanyu’s Dilemma is worth thinking about. Only when you enter will the real struggles or fruits present themselves.

A Framework for Selling

But we’re all in luck because Mohnish teaches us exactly how to think through a selling situation and provides a framework of how to do it.

The first point is to only enter an investment if the initial purchase satisfies it being within your circle of competence and if you with a high degree of confidence is able to determine the intrinsic value while buying at a significant discount to that intrinsic value (as explained in previous sections).

Now imagine the price drops significantly after entering the given investment that satisfies the above criteria and you’re looking at a painful paper loss. Should you sell?

Mohnish advises avoiding selling if:

- It’s less than 2-3 years since purchase since a few months is not long enough for a business’s value to have changed significantly.

- You are unable to estimate an updated intrinsic value with a high degree of confidence. Mohnish provides an example of a theoretical gas station whose cash flows become uncertain and a real case he encountered in his fund to illustrate this point. Clouds of uncertainty tend to clear over the course of several months, although it might take longer than expected.

- The presently offered price is below your initial conservative estimate of present intrinsic value.

Furthermore, if after three years the investment has not reached intrinsic value, Mohnish argues that one is likely to be wrong about the estimate of valuation or intrinsic value has decreased, and one should therefore sell. On the other hand, should the price rise to within 10% of intrinsic value, he recommends investors to think about going ahead and selling after taking account of the tax bite. Exceptions might include short term capital gains relevant for U.S. investors. Ultimately, if the price rises to or above intrinsic value, the investor should exit the Chakravyuha to look for other opportunities.

Abhimanyu faced a difficult dilemma. As a valiant warrior he was left with no other choice than to enter the one formidable Chakravyuha in front of him. He could not time his entry to his advantage, and with no exit plan, his unfortunate fate was sealed. We have the luxury of choosing just a handful of Chakravyuhas from over 30,000 over an investing lifetime spanning several decades. Entering these carefully selected Chakravyuhas at times when the soldiers are asleep all but guarantees successful traversals and big rewards.

***

In the last part of the book, Mohnish provides some invaluable resources for value investors to dig into and find opportunities. He ends the book by underlining the point about how investors need to focus on their circle of competence, and if they try to calculate everything and be everywhere, they’re very likely to do poorly. Once an opportunity appears within the circle of competence, one should study it closely, vet it, and make sure it’s trading at a discount.

While the book has been aimed at teaching readers how to maximize wealth, The Dhandho Investor is also about generosity and gratitude to the investment greats who have taught him and to those whom he is now teaching. Mohnish finds humility to be a bigger path to lasting success and fulfillment. I continue to be amazed by his clarity and life perspective.

I wish no one read The Dhandho Investor because it would make my investing competition much more intelligent. But I just can’t help recommending it.