Knowing something someone else doesn’t. That happens all the time. But rather than just having a piece of information that others don’t, keeping ahead of the curve by creating a moat to continuously keeping competitors out and achieving above-average returns is a different matter. In this article, we examine how companies can retain knowledge moats, how investors should think about them, and how to spot them.

Knowledge moats are made of the knowledge and capabilities in systems, processes, and people that competitors have a hard time copying, whether it’s complex manufacturing processes, decision-making algorithms, or special customer insight. Moats based on know-how are largely invisible but massively important. In fact, they’re probably at the top of the list of the most important factors in gaining a sustainable economic moat.

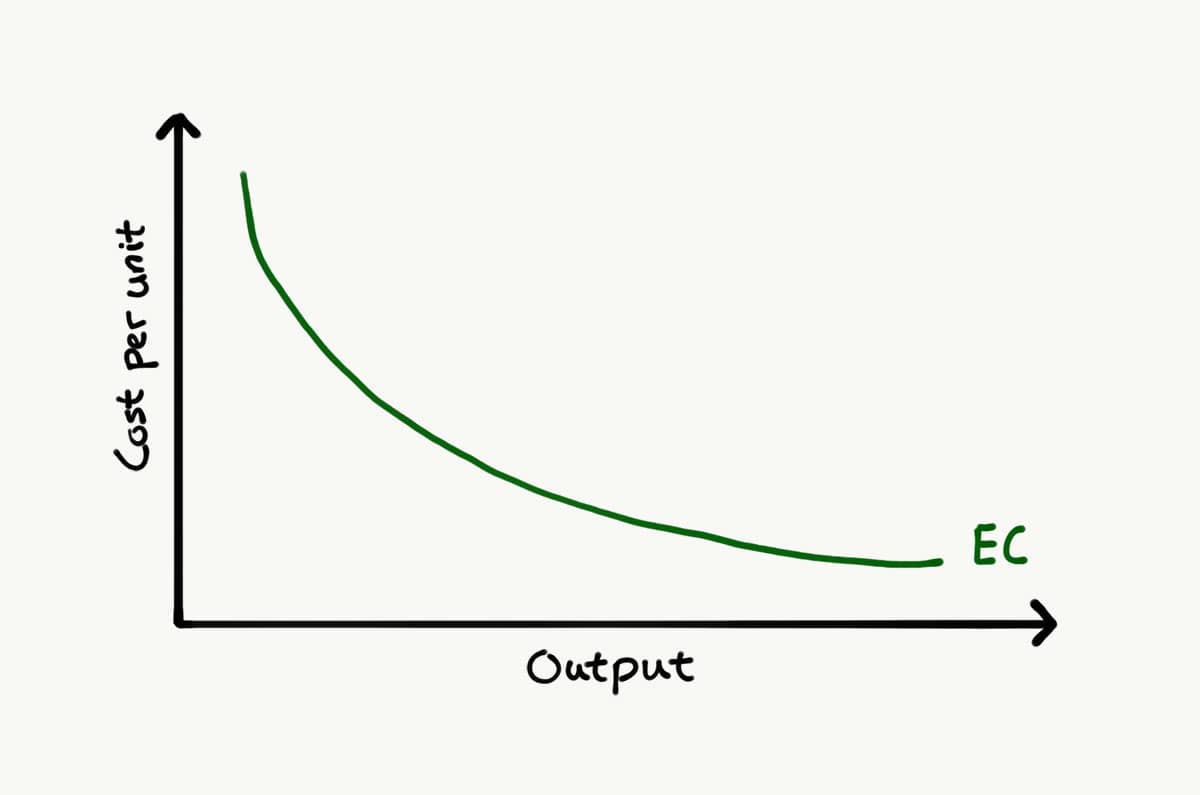

They appear through time. By doing something complicated in more and more volume enables human beings, who are trying to improve and are motivated by the incentives of capitalism, to do it more and more efficiently. In microeconomics terms, this means that there’s an inverse relationship between the total value-added costs of a product and the company’s experience in manufacturing and marketing it. So, as a company moves along its experience curve, its competitive moat becomes stronger and its output more cost-efficient.

Therefore, the skills, abilities, and experience of a company’s leaders and employees are critical factors in pretty much any industry and it has a lot to do with which businesses prosper and fail.

But knowledge is also largely fluid, whether it’s diffusing throughout an organization or from corporation to corporation. This is one reason many industries tend to cluster in specific locations, whether it’s high-tech in Silicon Valley or Shenzhen or financial services in New York or London.

When know-how expands from a specific group of people to an entire organization through experiences, processes, data, values, and information, it’s termed institutional knowledge. And as we will soon learn, an economic moat originating from institutional knowledge is a great case of why clear and simple processes and communication within an organization is immensely important.

Because reaching a high level of institutional knowledge very much has to do with reducing complexity. Simplicity allows knowledge to expand throughout organizations while allowing an organization to control that knowledge much better.

Think of Knowledge as a Map

The way to understand why reducing complexity tends to increase institutional knowledge is by thinking of knowledge as a map. Like a map, knowledge varies in scale and dimension, and it takes time to accumulate.

Because maps are reductions of what they represent, they are, of course, a lot less detailed than the real world. By taking out unnecessary details, a map is used to emphasize the aspects that matter by filtering out noise and reducing cognitive load. Think of the difference of usefulness between the normal map mode and satellite mode when using a digital map. Most frequently, the normal mode is easier to understand and is thus more useful knowledge to the user. And it’s much easier to transfer for someone else to understand it.

Just as zooming in on a map can reveal almost infinite amounts of details, real-world problems often involve complex obstacles and paths to solve them, which then reveal ever more obstacles depending on which path you take. If you zoom in too much, the value of the map as a navigational tool decreases, but the same is true if zoom in too little. The important thing is getting the necessary amount of details right through lots of experimentation and experiential knowledge. It’s about getting to the point of optimal detail with the least amount of distracting noise.

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.”

– Albert Einstein

Companies that solve complex bureaucratic problems understand this very well. Excessive bureaucracy is an example of overfitting a map leading to counter-productivity through needless processes and so forth. Examples here include that of Fintech businesses, such as the online payments platform Stripe that successfully has been able to solve a lot of painful red tape involved with payment processing across countries and jurisdictions. Stripe figured out a better map than traditional payment processes through the banking environment by using better technological knowledge.

Apple also understands this extremely well through design. A well-designed product makes complex things seem very simple by getting to the exact right amount of detail. It’s very easy to forget how many details are dealt with under the hood of a product such as the MacBook, until you use an alternative that hasn’t thought of every corner case that Apple has. Such user experience design is very much an art. And companies that master this art through experience are able to achieve a cutting-edge knowledge moat through a massive amount of feedback loops from consumers.

In other instances, when knowledge is based on a very high level of specialization in a narrow, complex area (e.g. aircraft manufacturing), the map requires zooming in to a fine level of detail. Here, getting to a knowledge moat is much more of a marathon rather than a sprint. Knowledge moats developed over a very long time can prove the most indestructible unless that knowledge becomes obsolete through developments of society. It didn’t matter how smart the horses were when the car came around.

Now, the question remains: If knowledge is like a map, wouldn’t it just be easy for competitors to take that map to the copying machine?

And here lies the limitations of the map analogy because the answer is that a perfectly fitted map is a very difficult thing for competitors to copy. Those competitors would have to test the product in countless situations to see how it reacts to all the corner cases. They might build superficially similar interfaces but would probably waste their struggles in trying to the wrong details right while never getting to the more important ones. In almost all instances, they would be better off studying their own users and building something more fitted to their own context and reality.

This doesn’t mean copying competitors is an insensible thing to do. Sam Walton with Walmart is a wonderful example of how to use copying to build your own competitive advantage. But skillfully copying strategies that work is pretty much a skill in itself, and Sam Walton was a master at that by working at it tirelessly. Persistent experimentation based on his competitors’ retail strategies in getting to know what worked in almost any scenario (and how to use that to blow ahead of those competitors) was Sam Walton’s knowledge moat.

The difficulty of copying knowledge calibrated through experience and lots of feedback loops is like trying to masterly play a piano by watching someone else’s fingers move. The difficulty of copying that is pretty much rooted in universal theory. Information theory and the closely related field of thermodynamics describe how easily patterns tend to gravitate towards disorder and information loss (through equivocation and the like). Tacit knowledge is subject to much conditional entropy through transmission.

One might think that having a vast amount of data would prove as an exception to this property since data is always fixed and is commonly based on a universal language not subject to equivocation. But as we will later uncover, a knowledge moat is much more dependent on human beings and how they use that data to gain an advantage. Efficiently utilizing data requires experiential knowledge as well.

So, having well-fitted, non-copyable knowledge results in a sustainable advantage, which you can only get through lots of experience as it is fragile and tends to dissipate during transmission. This brings us to the next section: How fragile is a knowledge moat and can they be retained or even strengthened?

The Risk of Losing the Knowledge Moat

Once a business possesses institutional knowledge and applies a continuous effort to retain it, it can be an unbreakable moat leading to all kinds of lollapalooza effects – like rapid innovation. But gaining and retaining institutional knowledge is a hard, ongoing process. There are all kinds of things that can erode and degrade that advantage.

Another word for institutional knowledge is institutional memory. And as with any other memory, it can be forgotten. While some of it gets translated into procedures and policies, most of it resides in the heads, hands, and hearts of individual managers and functional experts who are at risk of retiring or switching workplaces. People change jobs more frequently than in the past, and as the economy improves, that churn rate increases.

Knowledge also degrades when a new senior executive or CEO introduces a different agenda that doesn’t build on earlier knowledge or contradicts what was done previously. Company mergers are great examples of that and are probably a part reason why proposed synergies by investment bankers often turn into dis-synergies. Because human knowledge does not directly show up on in the numbers, M&A consultants tend to bowl them over, and what was once an invisible advantage not stated in the deal documents slowly fades away.

In its February 6th, 2020, edition, The Economist wrote in What it takes to be a CEO in the 2020s that modern leadership faces disruption of the nature of the CEO role and that mastering the tricky, creative and more collaborative game of allocating intellectual capital is essential.

An intelligent management makes sure to distribute intellectual capital throughout an organization. This means taking proactive measures to make sure that institutional memory remains within a business as key employees and leaders are replaced over time. Such valuable measures include mentoring programs that bridge the knowledge gap between younger employees and their more seasoned counterparts.

A sensible way to cope with this changing nature includes utilizing technology to create a process where employees can continually capture and curate institutional knowledge from their co-workers of all levels. Bridgewater Associates has a platform named Coach which is populated with a library of common situations, or ‘one of those’, and which are linked to relevant principles to help people handle those situations. Bridgewater employees give feedback on the quality of the advice that Coach provides to continually better the platform’s decision-making. Additionally, Bridgewater’s Issue Log records employees’ mistakes and what to learn from them. Intel has an internal wiki called Intelpedia which allows employees to capture and assess important terms, procedures, and historical incidents. See how these tools are again comparable to the map?

And, of course, no-one really remembers what isn’t interesting to them. That’s why the old maxim of getting happy customers by keeping happy employees is a fundamental law to business success. Now we’re getting close to the root of institutional knowledge.

But before we get there, it’s important to recognize that intellectual capital can work the other way as well, which the modern capitalistic system has proved during the financial crisis. That the financial crisis was even possible to the degree that it happened proved that intangible factors rule the modern economy through information and knowledge, but most of all trust. And while the success of modern businesses depends on their ability to turn knowledge into economic value, it brings along another class of behavior at certain corners of the informational economy: Greed, value-destructive short-termism, and systems that encourage fraud and misdemeanor. If scarce knowledge is mixed with an ill-designed financial incentive system, it’s a very risky cocktail.

So, scarce knowledge can both create and destroy. Correct incentive systems that avoid these factors are more vital than ever.

Remember: People do what they’re incentivized to do. If someone is paying someone to be irresponsible, that someone is likely to continue to be irresponsible. If people are incentivized to better themselves and would be happy to stay at the same corporation for years or decades to unleash their potential while being treated fairly, they will do so. If not, you can bet whatever knowledge moat the company previously had will not be sustainable.

And if we use the mental model of inverting, we can conclude that knowledge as a competitive advantage is also not just about knowing what to do in terms of technical processes or writing complicated code faster. It’s also very much about knowing what not to do in order to uphold the integrity and reputation of an individual or the institution. If people are happy and intellectually stimulated by their environment, they will want to protect it by being careful at doing the right thing. Such a company can gain a significant competitive advantage that is sustainable just by doing the right thing while its competitors go around acting irresponsibly.

“An ounce of prevention isn’t worth a pound of cure, it’s worth a tonne of cure.”

– Charlie Munger

We can now get to the following point: the growth and retention of institutional knowledge is pretty much a direct effect of the organization’s incentive systems which allow employees to unleash potential towards a common goal in a happy and intellectually stimulating environment.

Now, how does an organization create such a system?

First, a good system makes sure to include accountability of employees by holding their feet to the fire. And in connection, a support system needs to be in place to ensure proper risk-taking. That includes people who’ll lift a finger on other’s behalf – supporters to back risk-takers on their back, and say: “Here’s what you did wrong and here’s how we’re gonna fix it.”.

The “here’s what you did wrong”-part of that last sentence is immensely important. A good system makes sure to include brutal honesty because people are certain to be risk-averse to honesty when it pays to be so. As Damian Mason writes in Do Business Better:

Many corporate boardrooms are filled with enablers, only there they’re called “Yes Men.” They ascended to their positions by agreeing with people higher up than them. Good leaders don’t surround themselves with Yes Men and Yes Women. They know the peril of doing so. In the absence of truth and critical feedback, CEOs or business owners make terrible decisions. All the while being told how brilliant they are by their surrounding cast.

Most folks don’t want to hear the truth. They’re too weak to digest critical feedback. So they seek out enablers. Know this: It’s impossible to build the life and business you’re capable of by surrounding yourself with enablers.

Basically, what this means is to avoid the Persian messenger syndrome at all costs. In the Greco-Persian Wars, Persia sent out messengers to gather information. When the messenger brought bad news, he sometimes got killed. All messengers came to learn that it was just much safer to go away to hide than to bring home the news of the battle lost.

The Persian messenger syndrome may be a human innate emotional response to unwanted news, but it is not a very effective method of remaining well-informed. When important people within an organization aren’t well-informed, institutional knowledge degrades rapidly. Meanwhile, some of the biggest reputational risks, the worst kind, reside in companies that possess the Persian messenger syndrome. If a business possesses a strong knowledge moat but that advantage is loaded with a bunch of reputational risks, it’s something to stay clear of. The good system rewards the first messenger to come forth with bad news.

How to Spot a Knowledge Moat

So, how do you spot when a business possesses a high degree of knowledge and know-how as a sustainable competitive advantage? Well, it depends on the industry and it’s not easy when you’re not on the inside.

Knowledge does not show directly up in the numbers except to the extent that it gives the company a sustainable cost-advantage. This can be gauged by looking at the stability of its gross margin, but even then, the advantage might be attributable to another factor such as a locational advantage or vertical integration.

To really assess whether a company possesses a knowledge moat that is likely to be sustainable over many years, one has to not only know the workings of the company, but the workings of the industry itself to get to what really matters. While the purpose is not to get to expert industry knowledge in accordance with Laplace’s demon, it’s vital as an investor to at least get to the point of knowing what you don’t know about the industry.

Obviously, as an outside investor, looking at the age of the company is the first step. Even though disruption is an omnipresent term in the business world in current times, it’s logical to assume that the probability of an older company having a knowledge moat is greater than with a younger company (provided that the older company is doing well). As written in the above section on knowledge as a map, finding the right fit of details requires lots of experimentation and older companies have spent more time doing that experimentation.

And just as a free market economy operates very much like an ecosystem, narrowly specialized businesses also got a greater chance of having a knowledge moat because they have done that experimentation more intensely within a narrow niche. Of course, it’s not a given, but it does make sense to look at niche businesses when trying to uncover a knowledge moat. While Apple is an example of knowledge advantage applicable to a huge market, precision steel manufacturers to the aerospace industry are examples of businesses that can earn high, sustainable returns based on experience in a narrow niche.

Next step is to gauge the management and its own description of what advantage the company has gained through experience. Here, of course, it’s most productive to go to the first-hand source and meticulously read the Management Discussion & Analysis (MD&A) section of the company’s annual report – assuming that the stock is listed. Ask the following questions: How much weight does management place on the experience and know-how factor in maintaining or growing their competitive position? And is that description coherent with what is shown in numbers? For example, if management describes its production cost-advantage to technical know-how, check out the stability or growth of the company’s gross margin compared to competitors over the last 5-10 years.

Read backward through the company’s prior annual reports – preferably over a 10 year period – and then go sideways studying the competitor’s description of their advantage. Oftentimes, the knowledge gained from this practice is surprisingly sufficient as compared to reading industry reports or newspapers about the industry. There’s no shortcut to this practice.

Try to look for systems in place that aim to expand and retain the know-how and training of its employees. Get a feeling for the culture and the company’s incentive systems with a crucial focus on the latter.

Oftentimes, it’s not that hard to get an idea of a company’s incentive system. First, read through the company’s proxy statements and how management and the board are compensated and on what measures. Compensation should be linked to shareholder interests over the long-term. Focus not relentlessly on how much managers are getting paid but how they’re getting paid. Paying an important leader as a bureaucrat can be equally as bad as paying him or her excessively.

The level of pay has very little to do with whether or not CEOs have incentives to run companies in the shareholders’ interests. Incentives are a function of how pay, whatever the level, changes in response to financial performance. But, the level of pay does affect the quality of managers a company can attract. Companies that are willing to pay more will, in general, attract more highly talented individuals which know-how expands downward in the organization, and which potentially has a huge effect on the company’s institutional knowledge. On the contrary, a bureaucratic pay not linked to shareholder interests or performance is almost certain to lead to bureaucratic behavior. And that sort tends to create scapegoating effects down through the organization with ripple effects of other bad behaviors, especially during periods of poor performance.

Preferably, the CEO should own substantial amounts of company stock, and cash compensation should be structured to provide big rewards for outstanding performance and meaningful penalties for poor performance.

Next, try to figure out the incentive system of workers at lower levels which very much depends on the industry the company is in. Does paying by the hour work counter-productively and promote idleness at the given line of work? Are large bonuses being paid based on wrong recognition systems?

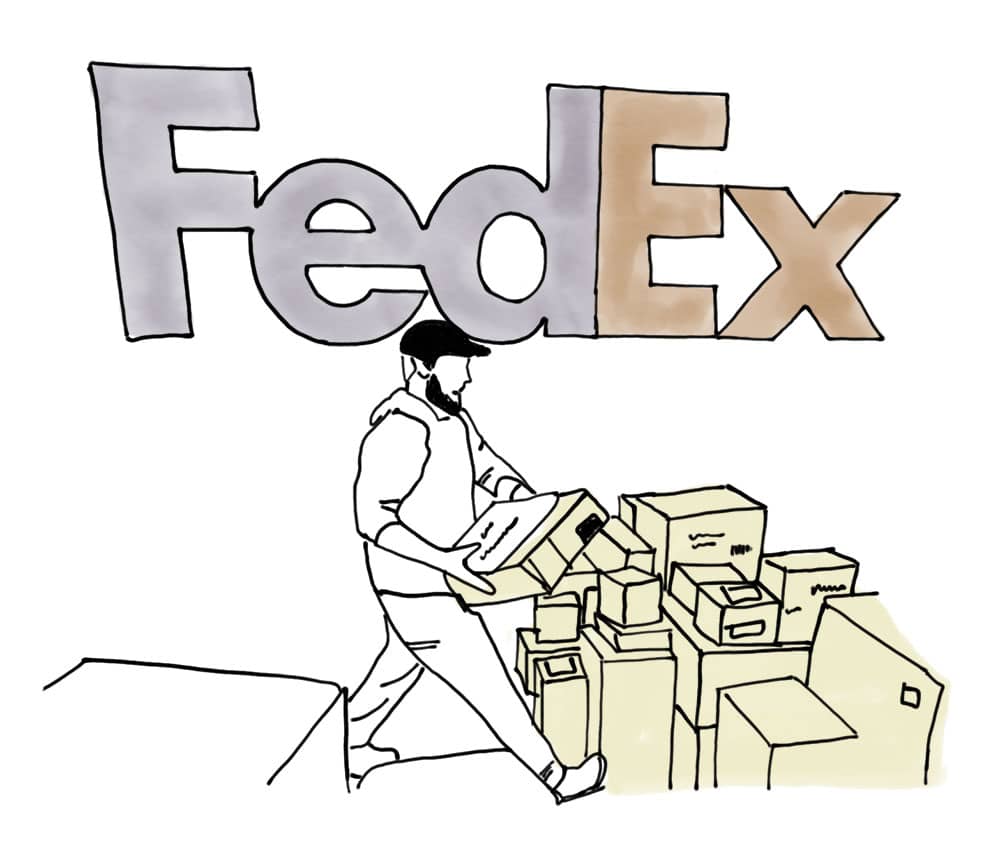

One of Charlie Munger’s favorite cases in point to explain the power of incentive systems includes that of FedEx. As he explains:

The heart and soul of the integrity of the system is that all the packages have to be shifted rapidly in one central location each night. And the system has no integrity if the whole shift can’t be done fast. And Federal Express had one hell of a time getting the thing to work.

And they tried moral suasion, they tried everything in the world, and finally somebody got the happy thought that they were paying the night shift by the hour, and that maybe if they paid them by the shift, the system would work better. And lo and behold, that solution worked.

Remember, as an external analyst, you’re not trying to grasp the full reality and every nut and bolt about the company’s knowledge. But it’s very important to aim at understanding the system behind it. Otherwise, you won’t know how rigid that knowledge is.

Be Creative

To get to understanding the company’s knowledge map, it’s sometimes not sufficient to utilize financial reports or internal information about the company. As value investors, we often need to use other information at our disposal to get to the qualities which are not reflected directly in company reports.

A study in the Harvard Business Review made in August 2019 found that there is a strong statistical link between employee well-being reported on Glassdoor and customer satisfaction among a large sample of some of the largest companies today. This relationship seemed particular strong in industries with the closest contact between workers and customers, such as retail, tourism, restaurants, health care, and financial services. Glassdoor is a very useful invention in getting to how companies treat employees. If employees are treated unfairly, rest assured that its possible knowledge moat is unsustainable.

Another classic method involves that of the scuttlebutt method – a homage to the great Phil Fisher. The scuttlebutt method is a way to conduct due diligence by getting out of the echo chamber and talking to all kinds of people of all levels related to the company, such as customers, current or past employees, suppliers, or competitors. Using the scuttlebutt method might get you to a deeper level of understanding about the minds and behavior within the company and industry. But beware of inherent biases or prejudices of the sources.

To learn more about Phil Fisher and the scuttlebutt method, read Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits.

Data as Knowledge

In today’s economy, having a vast amount of data over the competitors has long been lauded as a competitive moat for companies, and that narrative has been further hyped by the rise of new businesses contending to utilize artificial intelligence. But be careful to interchangeably use data and knowledge as the same type of advantage. As Andreessen Horowitz says in The Empty Promise of Data Moats:

Data is fundamental to many software companies’ product strategies, and there are ways it can contribute to defensibility — but don’t rely on it as a magic wand. Most of the narrative around data network effects is really around data scale effects, and as we’ve outlined in this post, those sometimes have the opposite effect if not planned correctly.

It can feel tempting to assess a business’s level of knowledge and the associated competitive advantage by simply looking at the amount of data the company possesses. Obviously, the largest tech companies have been able to use an advantageous amount of data to prosper tremendously. There are a lot of things that Facebook, Google, and Amazon know that other companies have no clue about. But taking that data as a direct causality is prone to bias from first-level thinking. Sometimes data can provide a moat in itself and other times it can’t. Make sure to determine when it can’t so as to not put a premium on the company’s data collecting capabilities.

It’s important to look at the company’s knowledge moat holistically.