Disney is a company everyone loves. Like Coca-Cola, the core concept of Disney is predicated on Pavlovian association. The product is there to make us all feel something, whether it’s happiness, nostalgia, or childishness.

Due to its incredible franchises, Charlie Munger once described the company as the equivalent of an oil company that can put the oil back in the ground after it is done drilling so it can drill again.

My fascination with Disney and its story went into high gear once I read former CEO (now Chairman) Bob Iger’s book, The Ride of a Lifetime. It’s one of the most enjoyable and knowledgeable business books out there.

However, according to the pari-mutuel system of the stock market, just because Disney is a unique company, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the stock is a fit for the long-term value investor at current levels. So let’s dive a bit below the surface to see whether that is the case.

A Bit Below the Surface

For a long time in its nearly 100-year-old history, Disney stayed clear of acquisitions. The reason was that it didn’t need to dabble in M&A. In its internal creativity Disney found abundance. No one could create what Disney could create and no one could persuade the consumer as Disney could.

The year 1995 was therefore a pivotal point in Disney’s history as it began a new acquisitive journey when Michael Eisner concluded a $19 billion landmark merger between Disney and Tom Murphy’s and Dan Burke’s Cap Cities/ABC. The top TV network, media giant, and owner of ESPN merging with the country’s premier movie producer, a combined powerhouse with 1995 sales of $20.7 billion dwarfing the then entertainment leader Time Warner Inc., was something that drew headlines. This is not surprising given that Disney’s market cap the day before the merger amounted to 60% of the combined value and it would turn out the second-largest merger in U.S. history. To get a feel for how big that deal was, at Disney’s current market cap of $319 billion, such a deal would require a similar-sized bet of $211 billion today.

The deal included a bonus for Disney because it was what brought Bob Iger to the company to start working under Michael Eisner and later succeed him. Getting Iger was a blessing. When he took over the helm in 2005, it was clear that he could tell how important the deal Disney/Cap Cities/ABC deal was to Disney’s power and how big of a masterstroke it was from Michael Eisner. (In the meantime, Disney also acquired Fox Family Worldwide for $2.9, starting what would turn out an extensive relationship between Disney and Fox). Over the decade following the Cap Cities/ABC deal, revenues increased 70% and EPS 50%. But Iger wasn’t constrained by those two deals and began to envision something grander in the creative atmosphere. I think it’s safe to term what happened from there an ‘acquisition spree’.

Ironically, or fortunately, part of what sparked Disney’s acquisition spree was consecutive failures in the creative department. By the time Iger took over, Disney had experienced a long series of box-office disappointments. The fact of the matter was that Disney couldn’t keep up with Pixar’s success, innovation, and animation technology. Where Disney had built its reputation on successes such as Snow White and Lion King, those productions looked generations old when Pixar came along with Ratatouille, The Incredibles, and Finding Nemo.

Iger knew something drastic had to happen so he decided to reach out to Steve Jobs, CEO and major shareholder of Pixar. He wanted to swallow the whole company to get its animation studio into the Disney fold.

When Iger and Jobs then settled on a $7.4 billion price tag, it showed Iger’s strength of conviction. Almost everyone thought the price was too high. But Iger humbly realized that internally building a studio like Pixar’s—generations ahead of everyone else—would be an impossible task to accomplish at a short time frame where Pixar could continue to chip away at Disney’s business in the meantime. And by getting a growing number of hugely successful franchises in the mix, $7.4 billion would be a bargain, he thought. The deal re-established Disney at the cutting edge of animation and Iger’s ride of a lifetime began.

From then on, Iger showed a willingness to pay up whatever it took to strengthen the Disney moat—so much so that some deals may have been perceived as undisciplined capital allocation. But Iger had another view. In his first earnings call as CEO, he said the following which showed how he perceived the value of Disney’s acquisitions like few could:

We intend to be disciplined in our approach to our current cost structure and our investments. […] This investment approach extends not only to our internal development, but also to how we approach acquisitions. As we have stated in the past, we do not feel the need to acquire assets just to get bigger or simply to wade into new space. We are prepared to move wisely and quickly in order to respond to rapid changes in the marketplace.

The next big deal came in 2009 with Marvel, creator of the almost cultish superhero universe that includes Spider-Man, Iron Man, Captain America, and so forth together with a large pool of latent goodwill. Marvel was scooped up for $4 billion.

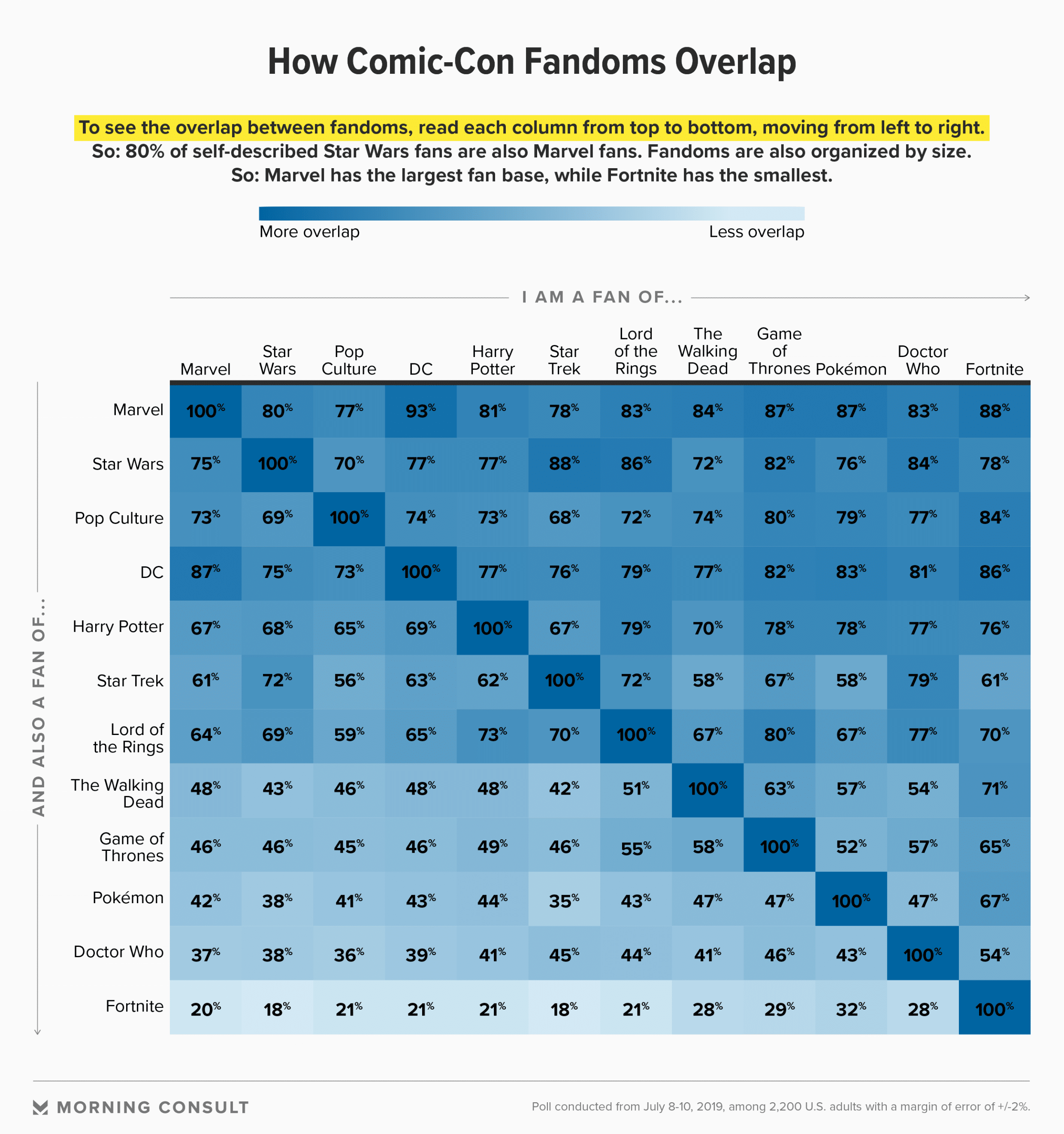

Marvel has arguably turned out to be Disney’s biggest contributor to its moat and the strongest brand with the most emotional attachment from the consumer. Capturing the imaginations of younger and older generations alike through its comic book history, Marvel has managed to leverage its fanbase to produce some of the biggest films in Hollywood. One 2019 study by Morning Consult showed that Marvel dominates pop culture with 63 percent of a nationally representative sample of 2,200 adults identifying themselves as Marvel fans.

Interestingly, the same study showed that the next most popular property was Star Wars, the child of Lucasfilm, with 60 percent adult fandom. Disney purchased Lucasfilm for $4.06 billion in 2012 in a 55% cash/45% stock deal which so far has made George Lucas—assuming he still holds his full stake—over $10 billion (even as Lucas has been quoted as calling the Lucasfilm sale very, very painful

). Also interestingly, the Morning Consult showed that Marvel and Star Wars in 2019 had the biggest overlap with other fandoms.

Whether this correlation is a function of Disney’s magic, Star Wars’ huge fan base, or a factor as to why Disney decided to pursue Lucasfilm remains unanswered. Either way, in Marvel and Lucasfilm, Disney kept growing its power and paid the price necessary for it.

And yet, even high price tags can turn out remarkable decisions if what you pay for carries enormous goodwill, latent potential, and synergy. Marvel and Lucasfilm turned out to be too cheap.

Through Marvel, Disney’s worldwide figure for box office sales alone has so far exceeded $22 billion dollars through 23 movies. The Avengers: Endgame raked in $2.79 billion over 87 days since its theater premiere—the highest-grossing film of all time. Add that to ancillary and spill-over revenues to e.g. Disney’s Parks, Experiences, and Products segment, and Marvel can safely be categorized as a remarkable investment. Disney didn’t plan on taking the Lucasfilm acquisition lightly either, rolling out five films and multiple TV series. The last four Star Wars films earned over $4.8 billion at the box office.

It didn’t come without obstacles, though. While Disney bought the rights to over 5,000 characters in the Marvel Universe, some of the big-hitters were constrained by contracts with rival film studios. One of the most popular heroes, and the hitherto biggest success on the big screen at the time of the Marvel acquisition, Spider-Man, was locked down by Sony. A “barter arrangement” from 1999 that granted the 007 franchise to MGM had given sole ownership of Spider-Man to Sony-owned Columbia Pictures. Not knowing what to do with Spider-Man in 2011 and needing a cash boost, Sony sold the merchandising rights back to Marvel. And finally, after several failed agreements around the film rights, Sony and Disney came to a licensing agreement starting from Spider-Man 3 (2021) in which Disney and Sony share the cost to produce the film and proportionately share the revenues. Now Sony distributes all the Spider-man films and Disney licenses the merchandise rights to third parties. The Incredible Hulk, a less popular figure from the Marvel universe, continues to be distributed by rival film studio Universal Pictures.

Disney has also made two acquisitions that preceded the DTC transformation we are seeing of the business today. One was a 30% stake purchased in 2019 of Hulu, an early-shot subscription video on demand (SVOD) service (the ownership of Hulu increased to 67% as a consolidated entity in 2020 when Disney acquired Twenty-First Century Fox, Inc. which will be discussed in a minute). The second was BAMTech, purchased over the course of 2016 and 2017 to 75% ownership for a total sum of $2.58 billion. BAMTech, a spin off from digital media company MLB Advanced Media, provides streaming technology which it licenses to third parties. Disney brought in BAMTech with the idea to provide a more in-depth streaming service for ESPN that could counteract accelerated cord-cutting. BAMTech’s technology now powers Disney’s ESPN+ offering.

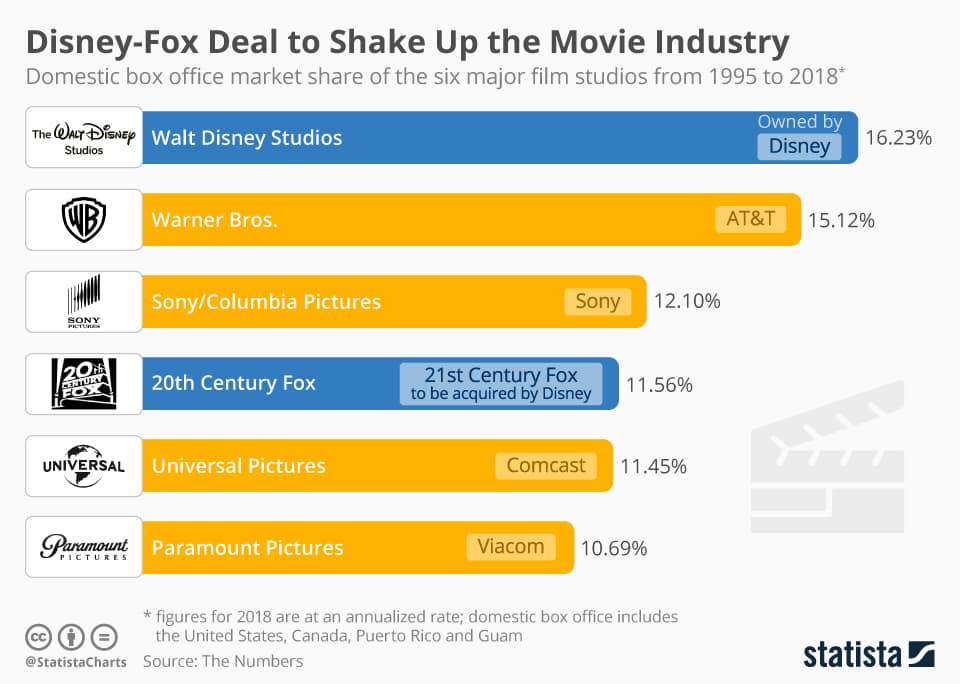

The biggest dollar acquisition in Disney’s history came in 2019: a $71.3 billion deal for 21st Century Fox. It was a big whale to swallow (which explains the price tag) but it’s also worth mentioning that the acquisition was the result of a bidding war with Comcast. While Disney planned to only pay $23 per share, they ended up acquiring Fox at a price 65% higher than that. Granted, Disney “only spent” about $56 billion (in cash and stock with 20% dilution) since it divested Fox’s stake in Sky to Comcast while keeping the Fox assets.

You can take two viewpoints in assessing whether that deal was intelligent.

The critical view is that while Disney bought some very valuable properties—including but not limited to The Simpsons, National Geographic, Family Guy, the Avatar sequels, X-Men, and a majority stake in Hulu—they overpaid for them. They’ve had so much success with prior acquisitions spinning gold on latent IP that it certainly would be the same case with Fox as the icing on the cake and that no price would be too high to achieve it. And by acquiring Fox, Iger would pound in his legacy as a fearless acquirer in his visionary pursuit of creating the best SVOD offering on the market just before handing over the keys to his successor.

The other view is that Fox’s assets were necessary properties to add to its upcoming Disney+ streaming service for it to become the staggering success everyone expected it to be; That the market for Disney+ wouldn’t be able to keep up with Netflix, HBO, and Amazon Prime Video without a larger library of quality content that catered to a target group over the age of 20. Disney stated before the deal that it projected to crystallize as much as $2 billion in cost synergies with an expected EBITDA contribution of $4.7 billion. Should these savings crystallize, Disney effectively paid less than 12x expected EBITDA. It’s tough to yet render a call on this since COVID hit the year following the acquisition and Fox’s assets are divided into Disney’s segments. My take is that Disney overpaid if they cannot crystallize the expected cost synergies but likely paid a fair price if they do.

Nevertheless, the Fox acquisition turned Disney into the unprecedentedly biggest box-office film studio in the world.

It’s no secret that Iger is going to be remembered as a well-respected, visionary CEO with leadership integrity. Jason Squire, professor at the USC School of Cinematic Arts and editor of The Movie Business Book has said that he is going to be viewed historically as a major mogul

. Doug Stone, president of Box Office Analyst has said: Disney is totally different than what it used to be 10 or 12 years ago. […] Iger came in and was laser-focused on increasing profitability.

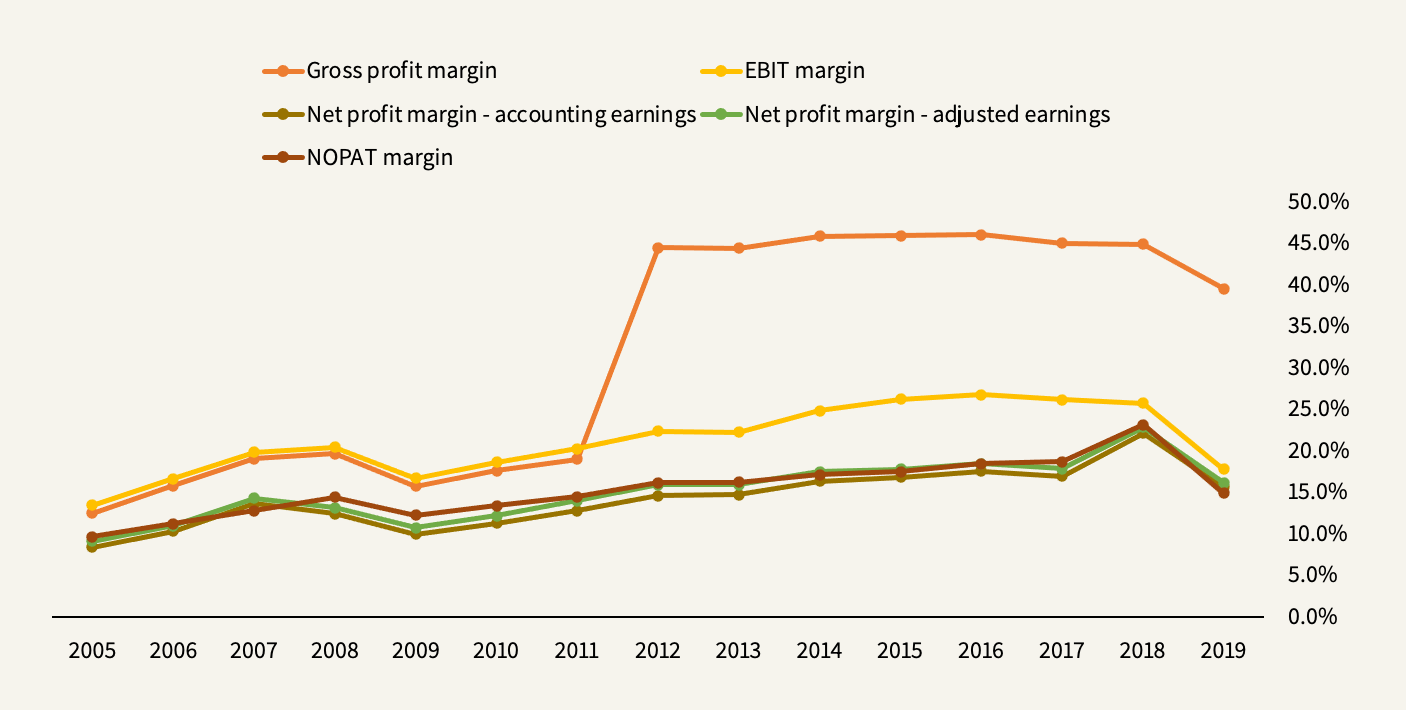

Increasing profitability he has. From 2005 to 2019, Disney’s revenues under Iger’s tenure more than doubled to $69.6 billion from $31.4 billion while EBIT almost tripled to $12.4 billion from $4.2 billion. And the margins over the time period:

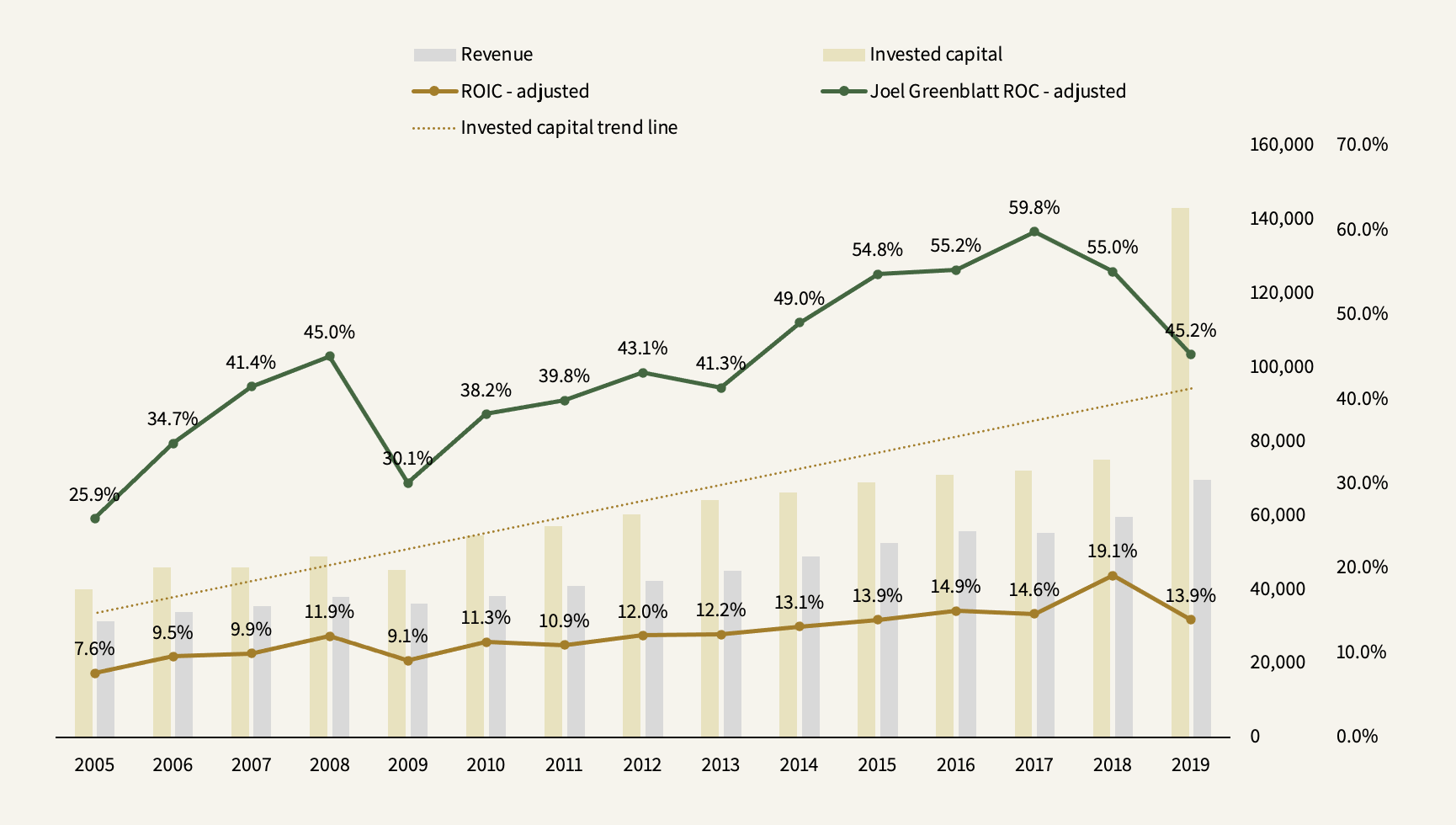

Of course, growth by acquisition brings increased size and additional profits when what you acquire are profitable businesses. However, here’s how Disney’s invested capital base (including goodwill) and returns on that capital have fared on top of the revenue growth.

Iger turned Executive Chairman on February 25, 2020, as he handed over the reins to prior Chairman of the Parks, Experiences, and Products segment Bob Chapek, who became the 7th CEO in Disney’s nearly 100-year history. (Iger did stay a little longer to ensure that the boat was being steered well through the fog of the pandemic). While Chapek has obviously had an impossible start to the job, I have yet to find a reason to believe that he isn’t as fit for the CEO job as Iger was. And that’s saying a lot.

Yet, there’s a vast difference between the two leaders. Chapek isn’t a Hollywood man as Iger was. While Iger believed that every transaction at Disney—parks, products, movies, and television—starts with creativity, Chapek, who’s mostly known for intelligently cutting costs and raising prices at the theme parks and resorts, is a data-driven decision maker. While the charismatic Iger—a friend of Oprah—is of polish and flair, Chapek is like a behind-the-scenes, bottom-line-focused businessman.

These differences blew into Chapek’s face a few months ago when Scarlett Johansson, the movie star in the recently released Black Widow, sued the company claiming that her contract was breached when the movie was released on Disney+ at the same time it debuted in theaters. Johansson accused Disney of using Black Widow to boost sign-ups for Disney+, sacrificing her box-office payday, while Disney accused Johansson of indifference to the effects of the pandemic. Insiders at Disney blamed the public fight on Chapek’s inexperience with handling talent. The suit was quickly settled.

Of course, handling movie stars is the tough side of working in Hollywood. And yes, maybe the public fight with Johansson never would have happened on Iger’s watch. But at a time where the company is puzzling to integrate a huge media acquisition, keeping costs in check, and embarking on turning its digital business transformation into a financial miracle that is likely to lower profits and returns on capital in the mid-term, perhaps the timing of a person such as Chapek entering the picture is not at all bad.

Disney’s Transformation

When thinking about the origins of Disney’s decades-long success, smart acquisitions must not be seen in isolation. Rather, Disney’s smart acquisitions were amplified by a matter of lollapalooza effects.

For instance, buying Pixar gave Disney economies of scope in its studios. And LucasFilm didn’t just allow Disney to make new Star Wars films; It gave Disney a valuable library which it could monetize via Buena Vista, its home video distribution division; It added a new source of revenue for the consumer products division; And it allowed Disney to capitalize on additional expansion in the theme parks division, feeding into its already strong pricing power. These are the lollapalooza effects seen in the gradually increased margins above.

Consequently, these lollapalooza effects also give the company an advantage in the transformation of digital entertainment. While rivaling digital media giants are inexorably threatened by Netflix and the revolutionary impact of digitalization, Disney possesses certain advantages that have yet to shine through the transformation Disney is undertaking with DTC. Through user data, Disney will improve its targeted advertising, possess a better basis on what movie/series franchises to double down on, and better know how to develop its parks and experiences. These advantages will ripple into all of Disney’s businesses other than DTC.

But it’s also worth acknowledging the fact that Disney was taking a shaky step into DTC. As ripple effects can go outwards, some ripples will go inwards and cannibalize existing business. Customers aren’t going to buy a Star Wars DVD if they can have access to the entire library for $7.99 per month (or $79.99 per year). Nor would sports fanatics pay up for an entire TV bundle if they can get what they want on ESPN+ (ESPN is often the most expensive part of a cable package). This near-term issue is bigger than one might think; In a normalized year, simply shifting content to DTC, between lost licensing (~$150 million from Netflix) and home entertainment revenues, is likely hitting earnings by well over a billion dollars.

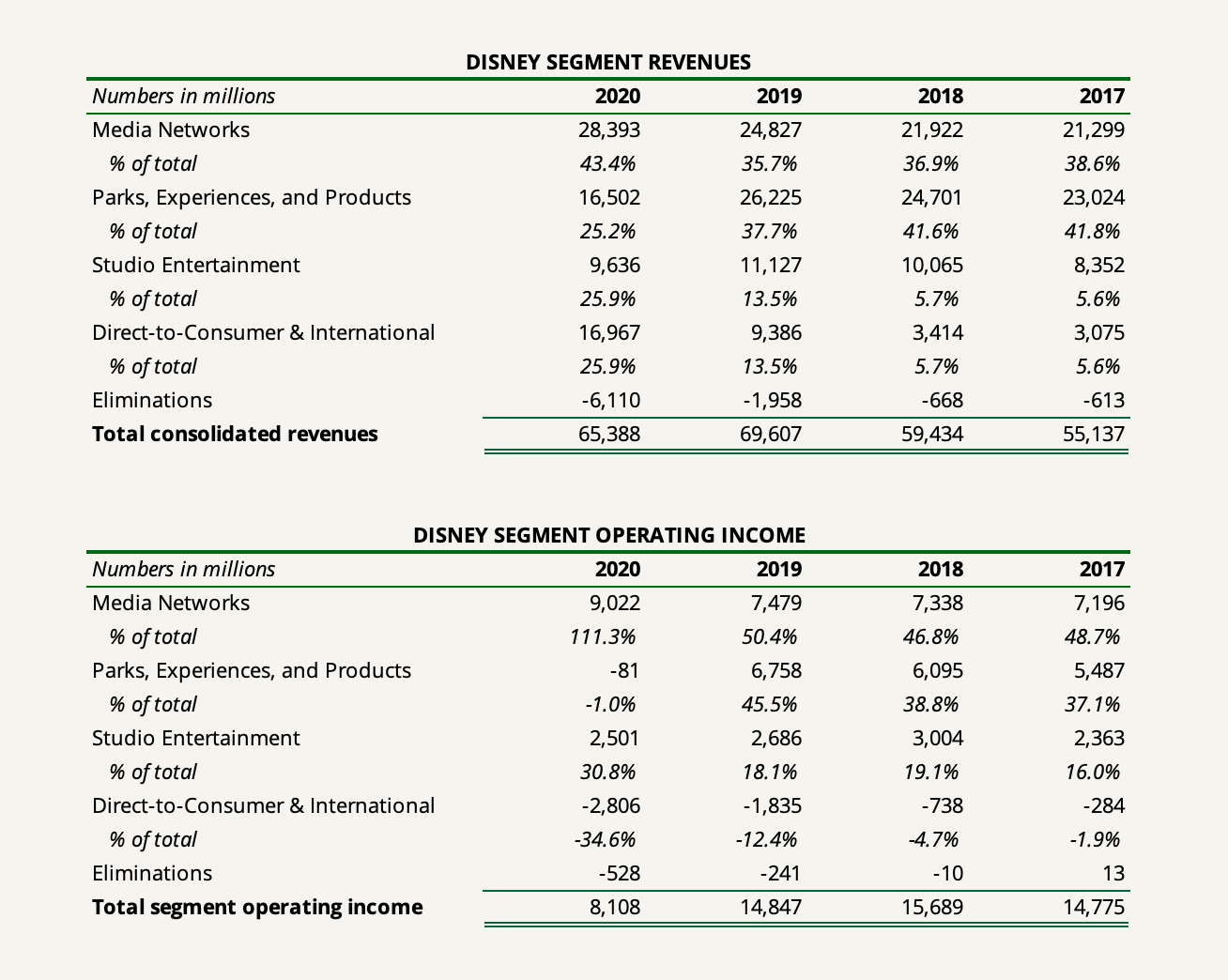

The Media Networks segment consists of Disney’s major cable networks including Disney, ESPN, Freeform, FX, National Geographic, as well as television production and ABC-branded broadcast television networks. It’s by far Disney’s biggest segment. Over the last four fiscal years, Media Networks has, on average, accounted for 39% of revenues and 64% of operating income—which was bumped significantly on a common size basis (and absolute basis from the consolidation of 21st Century Fox) as the company’s entire operating income in the Parks, Experiences, and Products disappeared altogether in 2020.

Note that in October 2020, Disney announced a strategic reorganization of the media and entertainment businesses which resulted in a rearrangement of the reporting segments. The four segments shown above were rearranged into two main segments: 1) Media and Entertainment Distribution and 2) Parks, Experiences, and Products. For the former, the company further decomposes the segment into Linear Networks, Direct-to-Consumer, and Content Sales/Licensing. Roughly, you could say that Linear Networks and Content Sales/Licensing collectively represent the previous Media Networks segment but since Studio Entertainment and the international television networks and channels are mixed around, this shortcut is a bit blurry. Since this discussion regards Disney’s historical performance, we’ll continue using the previous segment definitions for now but turn to the new definitions later as it regards valuation.

Now, while Media Networks is the largest, highly profitable segment, it’s also the one that’s in decline. Some of it has to do with the cannibalization effect mentioned earlier, but much of it is just a secular trend.

Satellite and digital cable rose to their days of glory in the 1980s and 1990s as massive deregulation led to an eruption of TV channels, making satellite TV and direct-to-home services one of the most common sources for news and entertainment around the world. But as we entered the millennium and portable devices became the norm, streaming, such as video-on-demand (VOD), over-the-top (OTT), as well as social media platforms, slowly entered the media landscape and picked up significant pace after 2010.

(Some technical explanation: VODs can be seen as the direct opposite of scheduled broadcast TV programming. It can be split into subscription video-on-demand services (SVODs), advertisement-based video-on-demand services (AVODs), and transactional-based video-on-demand services (TVODs). Most modern media, including Netflix, Amazon Prime Video+, HBO, Hulu, and Disney+, are categorized as SVODs, while examples of AVODs and TVODs are YouTube and the iTunes Store. OTTs, on the other hand, can be seen as subsets of VODs because it includes all streaming services that previously were transmitted by satellite or cable but is now delivered via the Internet. Sometimes, the term is also used to describe text and video call services such as WhatsApp. SVOD and OTT are often used as synonyms in describing services such as Netflix and Disney+ so which designation you use between the two doesn’t matter much.)

The rise of VODs and OTTs led the number of pay-TV subscribers in the U.S. to peak about half a decade ago and the pace of cord-cutting is only just picking up (65% of Americans still pay for cable TV). But you really see the future of media in this statistic: Today only 28% of view time is devoted to traditional TV while 68% go to streaming.

According to eMarketer, the US had 100.5 million pay-TV households in 2014. By 2019, the number was 86.5 million. Some forecast that it’ll go below 70 million by 2025. A survey by The Trade Desk predicts a whopping 27% of households will cancel their pay-TV package this year.

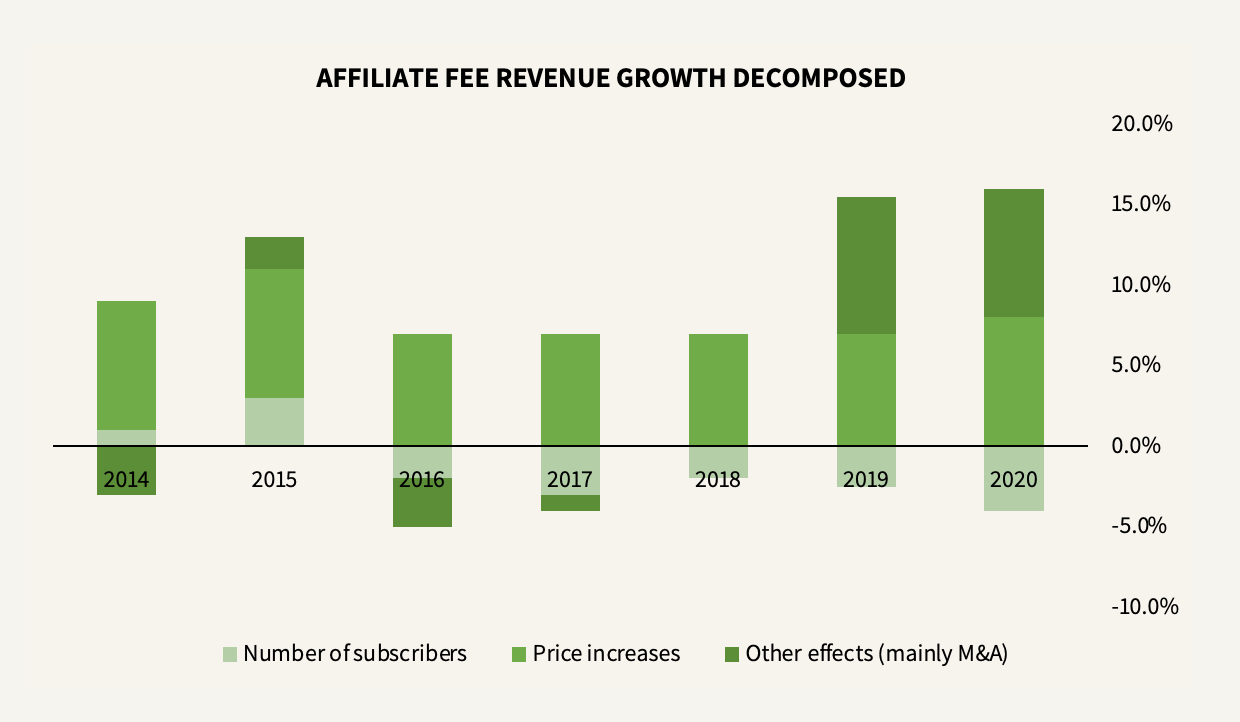

Now, looking at the absolute revenue numbers above, one might think, “Well, it can’t be that bad since Disney’s Media Networks revenues from 2019 to 2020 increased from $24.83 billion to $28.39 billion, an increase of over 14%.” But that kind of thinking is wrong. A large part of the growth came from the consolidation of 21st Century Fox, contract price increases, increased inter-segment sales of programs to Hulu and Disney+, and an added benefit from an additional week in the fiscal year. As a matter of fact, the growth in affiliate fees was partially offset by a 4% decrease in subscribers. This is not something to glance over. Because affiliate fees, which take up 53% of Media Networks revenues, come with high incremental margins (Media Networks revenues grew 14% while operating income grew 21%, implying operating leverage of 1.5x), inevitable declines in fees have a disproportionate impact on Disney’s bottom line.

On a comforting note, the way Disney has held up despite the trend has been through the aforementioned price increases as seen below.

In some cases, price increases indicate a sustainable competitive advantage. Yes, that is the case for Disney, but the window is shrinking. Price increases of the kind Disney has relied on are likely not sustainable even in the mid-term (and possibly in the short term) as the value equation for pay-TV becomes ever less compelling. At some point, I find it likely that the dampening effect of price increases will slow down or come to a halt. When it happens, operating profits will face significant headwinds.

Is pay TV dying a slow death? I don’t think so. The trend will fade to a certain level. Demographic tastes and the appeal of local TV could still drive the media. And you could even make the case that live events such as news and sports could provide support even though ESPN and ESPN2 each have lost roughly 15 million subscribers since the fiscal year of 2013. Yet, you can see how Disney’s Media Networks segment is under pressure and why it’s hard to determine its terminal value.

But of course, management saw all this coming. In 2019, Iger said to Barron’s:

What I posed to my senior team and ultimately to the board [in 2016] was, ‘We can’t sit back and let this happen’… Our ability to endure was going to be solely tied to transforming ourselves, and not pursuing a strategy of, ‘We’re going to get through this, it’s a storm that’s passing overhead, and when it clears, we’ll be fine.’ We have to be different when that storm clears. We can’t be the same. What we really needed was to lock arms and say this period of transformation that will now be more self-inflicted is going to require a reset, including on Wall Street… If you’re investing for the future, and you’re spending to create a new business model whose revenue is going to lag the launch and the expense of the initiative, then your profits are going to go down… If you’re going to look for traditional metrics to measure performance, it’s not going to work.

What we can infer from this statement is that Disney would be willing to invest whatever it takes to make DTC work. It also indicated that they needed to hurry. By the time Disney launched Disney+ in November 2019, Netflix had already amassed a paid subscriber base of over 167 million people in over 190 countries. Disney’s Hulu had 29 million paid subscribers at the time.

On subscriber metrics, the launch of Disney+ was a smashing success. When the company started hyping its release and announcing its list of shows and movies to be found on the service, the price was the last thing people talked about. People instantly subscribed pre-launch based on feelings of nostalgia and excitement. The service attracted nearly 30 million subscribers in the U.S. within three months of launch. It soon rolled out worldwide, and according to the Q3 2021 earnings report, the current number of paid subscribers on a global basis was 173.7 million across Disney+ (116 million), ESPN+ (14.9 million), and Hulu SVOD + Live TV (42.8 million) on July 3rd when the fiscal quarter ended.

However, there’s a reason why the price wasn’t what people talked about. I find it likely that Disney priced Disney+ too low to gain traction and was forced to play catch-up with Netflix, HBO, and Amazon. To customers, the price point was just too good to ignore.

It reminds me of a story between a west coast investor and an east coast investor. The west coast investor pitches a company to the east coast investor and says, Look, this company has grown its revenues at over 20% for the last eight quarters. At this rate, this company deserves a price-to-sales of at least 20x.

The east coast investor looks at the numbers and says, Well, of course it’s growing so fast… At this product price, it’s giving the customers all the value for free!

On that note, let’s dive deeper into the unit economics.

DTC Unit Economics

The real question with DTC is whether the economics are better than Disney’s legacy business in Media Networks.

For one, there’s the argument that cable subscribers have been overpaying and that the streaming era is showing up to rationalize that pricing. Who wants to pay over $100 per month for cable TV in this day and age? And who wants to be forced to pay $18 per month for ESPN in a bundle if they don’t even care about sports?

Across its slate of TV networks, Disney receives $15-$20 per month from MVPDs which is a significant premium to revenues per user gained in streaming. In Disney+, Disney barely gets over $4 ($4.16) a month per subscriber, and ESPN alone goes from getting Disney $9+ per month for cable subscribers to just $4.5 a month per subscriber to ESPN+. The Hulu SVOD gets Disney over $13 a month per subscriber, primarily from the addition of advertising revenue while the Hulu Live TV + SVOD service gets $84 per month (on an inconsequential 3.7 million subscribers out of Hulu’s total of 42.8 million). Disney doesn’t break streaming revenues out into global regions as Netflix does, but as far as we can tell, the ARPU figures are suppressed by Disney’s increasing international presence (such as Disney+ Hotstar in India) that are offered at lower price points.

Even with 131 million subscribers in Disney+ and ESPN+, it’s hard to get by on $4 a month. So what’s in the cards in terms of price increases? Well, Disney already increased the price for Disney+ once in 2021. When the service was launched in the U.S., the monthly price came in at $6.99, or $69.99 per year, and now it’s at $7.99, or $79.99 per year. In some countries, the price is steeper, such as in Denmark where the service costs 79 DKK a month ($12.30), and in other countries, the price is lower, such as in Indonesia where the service can cost as low as $0.80 a month. In the U.S., you can also purchase the entire Disney+, ESPN+, and Hulu bundle for $13.99 a month, or $19.99 a month with no Hulu ads.

Compared to Netflix, Disney+ (or the bundle) is a no-brainer for consumers. Netflix offers three tiers. A standard subscription in the U.S. comes in at $13.99 a month with no annual deal offered where you can watch stuff in 1080p. You can also buy a basic subscription for $8.99 a month where you can only watch in 480p (I don’t know why anyone would want to do that other than to test it out and either churn or upgrade to the standard later). Lastly, the premium subscription costs $17.99 and offers 4K resolution. In contrast, Disney+ offers 4K at no extra cost.

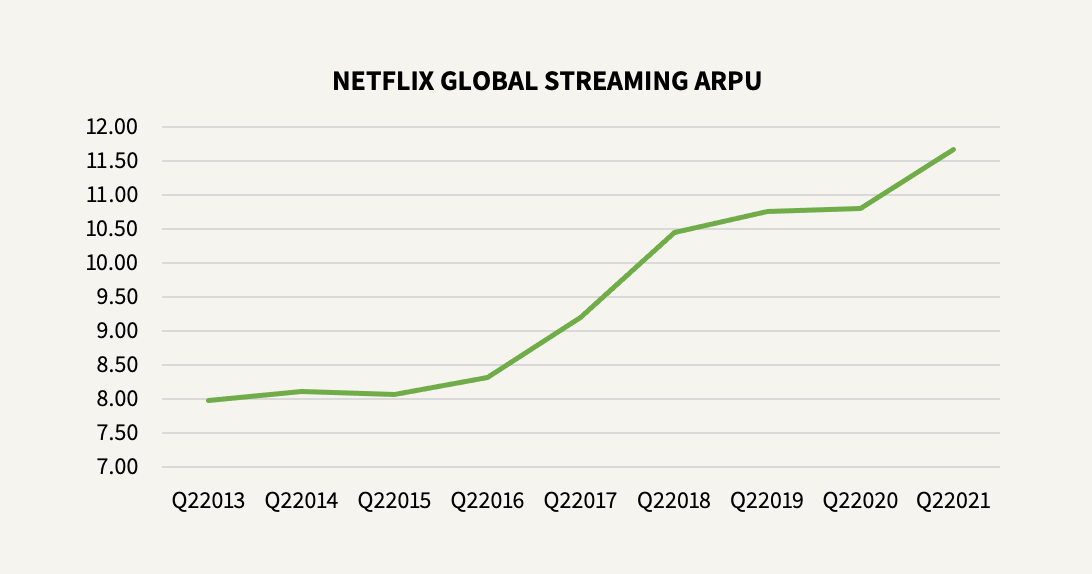

According to the Q2 2021 earnings report, Netflix earns a monthly ARPU of $14.54 in its UCAN markets (44.35% of subscriptions revenues), $11.66 in its EMEA markets (32.90%), $7.5 in its LATAM markets (11.80%), and $9.74 in its APAC markets (10.95%). The global average monthly ARPU is $11.67. Eight years ago, in Q2 2013, it stood at $7.98 which is a cumulative increase of ~46% and a CAGR of 4.87%.

It’s very likely that Netflix can keep raising its prices. Therefore, It’s hard not to come to the conclusion that Disney+ with its dominating consumer mind share will be able to raise prices significantly over time.

But the problem is that it starts at such a low point. If we assume a $.75 monthly price increase on average globally per year (a higher CAGR than Netflix), it would take Disney+ over a decade to reach Netflix’s current consolidated ARPU. You could make the case that one has to view Disney’s DTC offerings collectively which changes the picture since Hulu earns a lot of revenue from ads. But then you would have to remember that the cost structure for managing three unique subscriptions businesses is very different from managing one. And even if we do view them collectively (which we will in a minute because Disney doesn’t report cost structures for each separately), the current monthly ARPU for all three comes out to $6.73, taking six and a half years to reach Netflix (even assuming that Hulu SVOD and ESPN+ can sustain the same kind of price increases as Disney+).

As a side note to the above, activist investor Dan Loeb wrote a letter to Bob Chapek in October 2020, urging Disney to consolidate their DTC offerings. In the letter, he wrote the following:

We believe that collapsing all of Disney’s DTC services into the Disney+ application will simplify the product and be a meaningful enhancement to Disney’s offerings. Given that Disney+’s subscriber base is already meaningfully larger than any of your other DTC services, we believe Disney would benefit from a single customer acquisition vehicle led by Disney+. We understand that each of your DTC services – Hulu, ESPN+, and the upcoming Star offering – serve different demographics and may have various value propositions, but these challenges can be easily circumvented through tiered and bundled product offerings at various price points. Importantly, all product offerings should lead with the company’s marquee Disney product and brand.

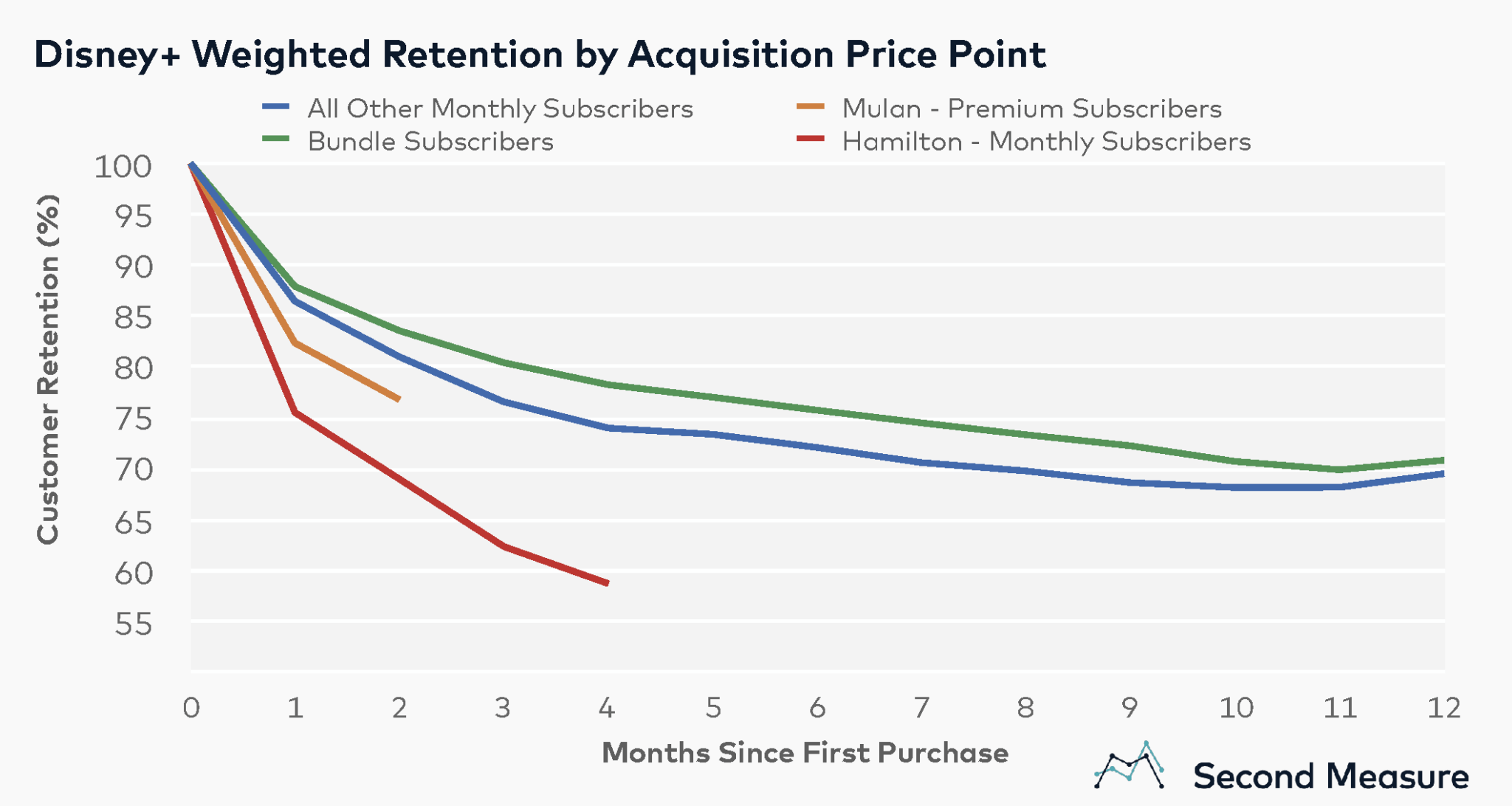

What about retention and user growth? According to Second Measure, Disney+ retains ~70% of users on a twelve-month basis, no matter if the subscriber is a bundle or standalone subscriber. I would venture to guess that Hulu and ESPN+ lie a bit below that but surely over 50%.

Like Disney+, Netflix also retains about 70% of subscribers annually. Think about that. That Disney+ retains about the same amount of subscribers as Netflix at more than half the price could tell us one of two things: 1) It either reinforces my suspicion that Disney+ was priced too low and that the factor that matters to consumers isn’t the price but the breadth and quality of the service, or 2) that Disney+ is an inferior product. I lean towards the former.

To figure out the growth potential of net new subscribers, the interesting thing is how much room there is in the market. Because the share of wallet with consumers currently is low for any streaming service, a rising tide lifts all boats. According to Mordor Intelligence, in 2020, Netflix had a total U.S. household penetration rate of ~74%, followed by YouTube with ~54% and Amazon with ~33%. A Deloitte report claims that of the 82% of Americans subscribing to a paid video streaming service, they on average subscribe to four different services.

But newer additions to the market create incentives for people to shop more around for the content they love. The latest research by Kantar actually showed that Netflix’s U.S. penetration took a dip to 67% in 2021. This might give a good indication that 70% marks the saturation rate in the U.S. So if we then assume that The Information is right (based on a review of internal data) about the claim that the North American subscriber count for Disney+ stood at 38 million out of 110 million back in February, it would equal a ~27% penetration rate based on U.S. and Canadian household data, still implying plenty of room to grow in its higher-priced markets.

Additionally, when Disney+ passed 100 million subscribers this March after 16 months of operation, Disney execs said the service was on track to meet its projections of 260 million subscribers by 2024 with 350 million total subscribers across the bundle. For the bundle, that would equal a subscriber CAGR of ~24%. I don’t have any better guess than them, but remember that a large part of that growth will have to be found in lower-priced markets.

On to costs. The main expenses incurred in the streaming business are related to production, marketing, and technology. The higher losses shown in the DTCI segment are attributed to these costs. We want to divide them into what is spent on servicing existing subscribers, what is spent on corporate, and what is spent on acquiring new subscribers (CAC). As for the latter, of course, a lot of the early subscribers gained for Disney+ were acquired at a $0 CAC based on brand awareness. As the service grows, that’s no longer the case.

For the nine months ended July 3rd, 2021, Disney reported DTC revenues of $11.76 billion and an operating loss of $1.05 billion. This equals operating expenses of $12.81 billion, or ~$17.08 billion on a linear rolling basis.

If we assume the total DTC subscriber count will have grown to 190 million by this fiscal year-end (which ended 16 days ago), Disney would have added 119 million gross new subscribers throughout the period with a TTM ARPU of $80.70. If we then assume that 10% of the $17 billion in expenses are administrative ($1.7 billion), that 10% of the remaining $15.3 billion spent on production, marketing, and technology ($1.53 billion) is spent to retain existing subscribers, we have $13.77 billion, or 80% of the remaining, left to acquire new subscribers. On 119 million gross new subscribers added over the time period, that works out to ~$116 in CAC.

Valuing the DTC business

Based on the preceding discussion, I would value the DTC business (Disney+, ESPN+, and Hulu collectively) as follows.

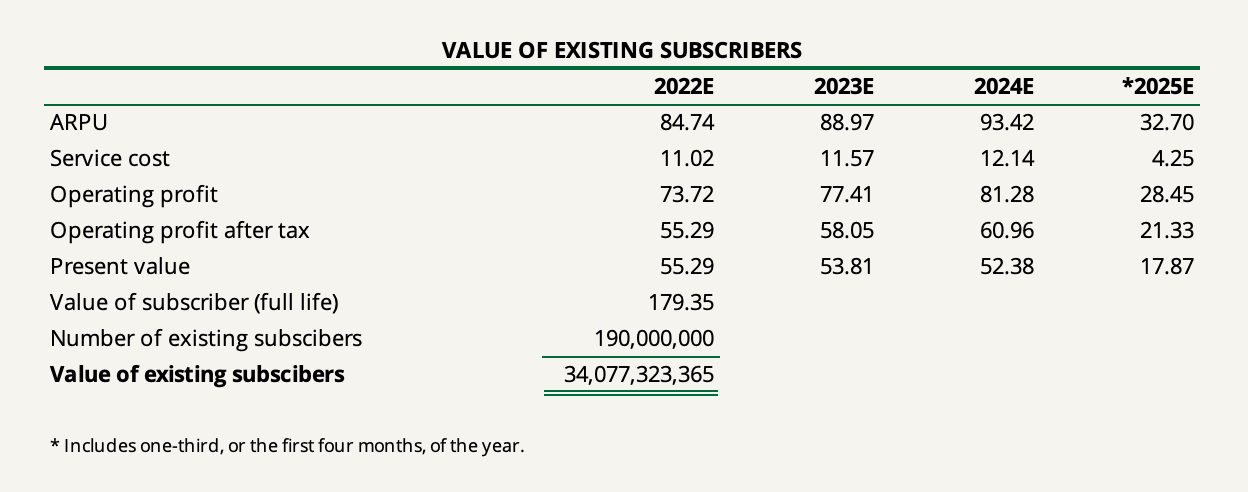

Valuing Existing Subscribers

- Subscriber count of 190 million by end of fiscal 2021.

- 2021 ARPU of $80.70, growing by 5% per year.

- Subscriber lifetime of three years and four months based on 70% annual retention.

- 87% gross margin ($1.53 billion service cost divided into $11.76 billion revenue).

- International tax rate of 25%.

- Cost of capital of 7.88% based on 10% opportunity cost of equity and 2.39% after-tax cost of debt weighted at the capital structure as of the end of fiscal 2020.

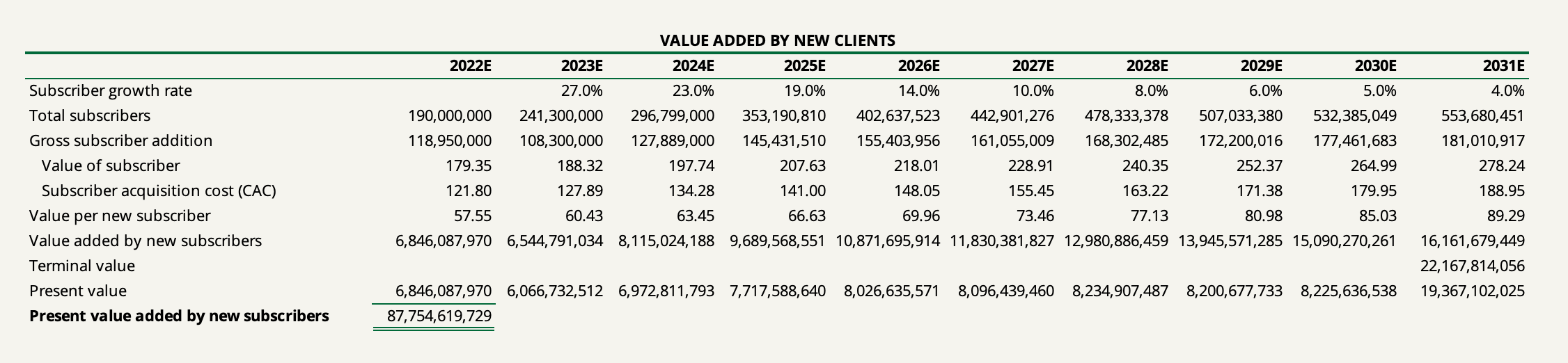

Value Added by New Subscribers

- Net new client growth rate of 27% in 2022E falling to 3% after year 10.

- Growth in value of subscriber of 5% falling to 3% after year 10.

- Growth in CAC of 3%.

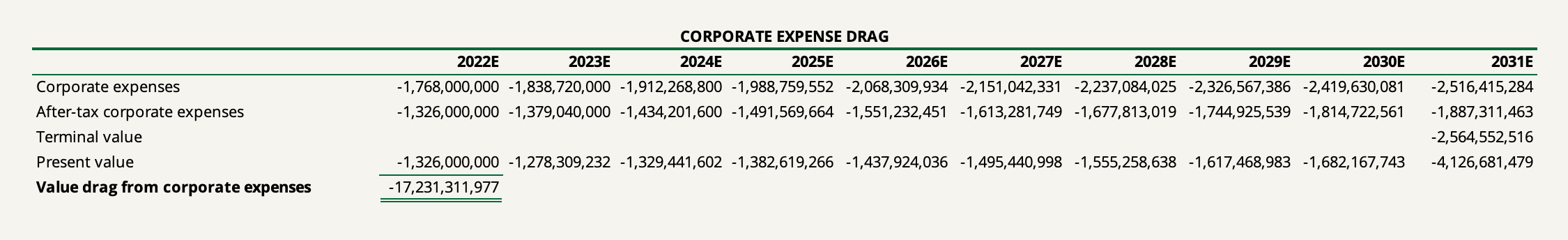

Value Drag from Corporate Expenses

- Corporate expense growth rate of 4% falling to 3% after year 10.

- International tax rate of 25%.

Bringing together the three components, we get a value of the operating assets for Disney’s DTC business of ~$108 billion.

Valuing the Rest of the Company

The majority of the attention of this write-up has been given to DTC. While it should in no way undermine the importance of the rest of the company’s activities, it has been a testament to the fact that a large part of Disney’s value (and its current market cap) lies in the contingent future of DTC. If we were to value Disney’s business excluding DTC, we would very likely stretch the numbers to an unfair degree to even come close to the current price of the company.

I’m therefore going to keep the rest of the valuation simple.

What we’re left with are either mature businesses (Parks, Experiences, and Products) or stagnating businesses (Linear Networks and Content Sales/Licensing). All have been hit hard by the pandemic.

Parks, Experiences, and Products

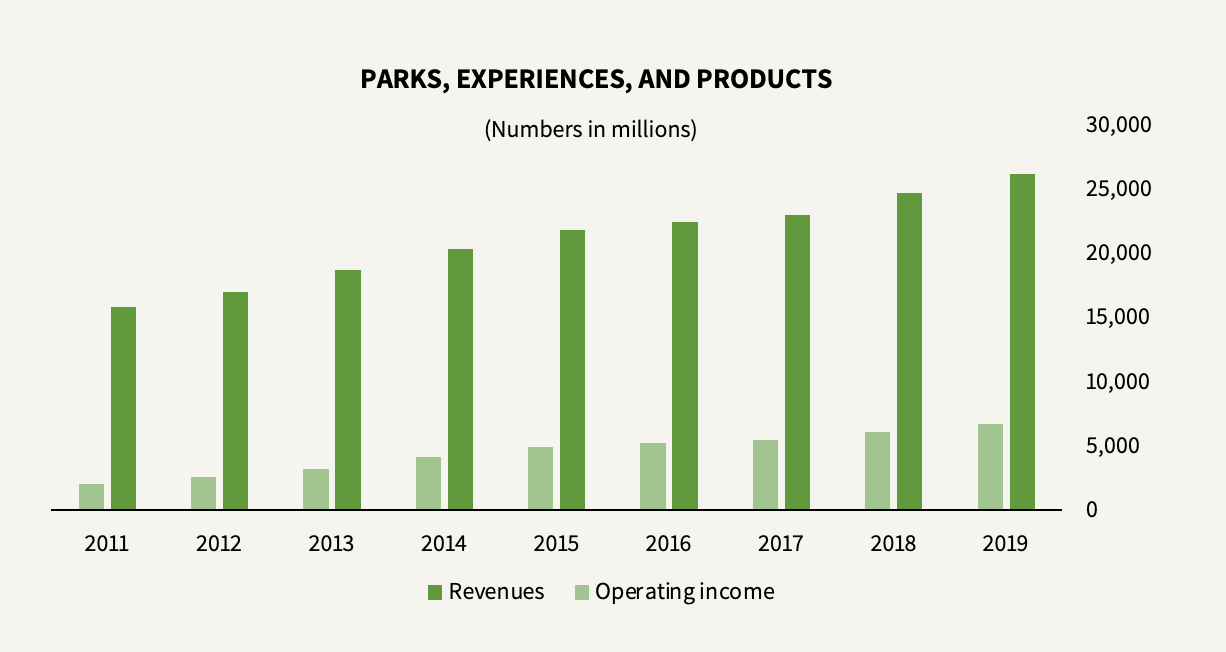

Parks, Experiences, and Products, which includes Disney’s iconic travel and leisure businesses (including six resorts, a cruise line, a vacation ownership program, the global consumer products operations, and so forth), used to fire on all cylinders, accounting for 40% of Disney’s consolidated revenues and operating profits in a normalized (i.e. pre-COVID) year.

When Chapek was chairman of the segment, he oversaw the largest investment and expansion in the parks’ sixty-year history, including the grand opening of Shanghai Disney Resort, a near doubling of the cruise line fleet, and the opening of the Star Wars and Marvel lands at Walt Disney World Resort and Disneyland Resort. Meanwhile, the company had realized that few businesses in the world possess the same pricing power as their own parks. So while Disney has always raised prices, they took it up a notch for the past two decades. Over the past 50 years, since 1971, the price of admission has grown by an inflation rate of 7.4%.

Those two factors leading to increased attendance and per capita spending, coupled with economic expansion, led the entire segment to generate $26.2 billion of revenues and $6.8 billion in operating profits in 2019, up 63% from five years earlier.

Then COVID hit, clearing all profits. In 2020, Parks, Experiences, and Products generated revenues of $16.5 billion, down 37%, while operating profits were just in the red, losing $18 million. The business hasn’t bounced back yet. For the nine months ended July 3rd, 2021, it generated an operating loss of $169 million on revenues of $11.1 billion.

When the business does bounce back, however, I would venture to guess that it would be able to reach its pre-COVID level, which may happen in 2022 (or it might have a long way to go but let’s remain a little optimistic). So in a normal year, we are dealing with a very stable business with high normalized earnings power that grows about 10% per year from economies of scale.

But Parks, Experiences, and Products is also a capital-intensive business. In recent years, excluding 2020, more than 75% of Disney’s total capital expenditures have fallen to this segment. In 2019, Disney spent $4.1 billion in capital expenditures. Compared to a depreciation expense of $2.3 billion, you could say that’s a lot of growth CapEx. However, since I think increasing CapEx is required to maintain the business, maintenance CapEx would lie somewhere between depreciation and full CapEx. The main idea is that solely looking at operating income likely overstates the results.

So, if we assume that Parks, Experiences, and Products bounce back to its 2019 level, we roughly have a business earning a NOPAT of $5.1 billion at an international tax rate of 25%. Then, adding a depreciation expense of $2.3 billion and subtracting net CapEx of $4.1 billion gives us free cash flows of $3.3 billion. If we slap a 20x multiple on that (or 7.3x EBITDA), the business would be worth $66 billion.

Linear Networks and Content Sales/Licensing

A big part of this write-up has already been spent discussing Disney’s future in Linear Networks (the legacy of Media Networks). The conclusion was that, although the business is currently highly profitable, it’s hard to determine its terminal value. Since Linear Networks is also a fairly stable (yet stagnating) business, my solution is simple: We slap a lower multiple on the business than we did on Parks, Experiences, and Products.

For simplicity, we are throwing Content Sales/Licensing in there as well. This business (the legacy of Studio Entertainment) is slowly shrinking to mainly include theatrical distribution. TV and SVOD distribution has become a decreased business since Disney made the shift from licensing to third parties to distributing the content itself. And home distribution is trending that way as well. As the company has shown a commitment to shrink the window between theatrical release and various home video options, Disney+ is increasingly becoming the preferred outlet after the theaters. So what we’re left with, in the longer term, is pretty much theatrical distribution accounting for the bulk of the business with ancillary activities such as music distribution, licensing of live events to Broadway and around the world, post-production services through Industrial Light & Magic and Skywalker Sound, and a 30% ownership interest Tata Sky Ltd taking a smaller share. For the past nine months ending July 3rd, revenues generated from Content Sales/Licensing amounted to ~25% of the revenues generated in Linear Networks, while the operating income amounted to less than 10% of the operating income generated at Linear Networks (of course, impacted by COVID which had a disproportionate effect on theatrical releases and home distribution.

If we take the past nine months’ collective operating income for the two segments on a rolling basis, we have an EBIT of $9.9 billion. Adjusted for an effective tax rate of 21% (since Disney’s linear networks are largely domestic), we have $7.8 billion of NOPAT. Assuming that depreciation equals CapEx from which all go to maintenance going forward and that 80% of the total segment depreciation expense on a rolling basis of ~$600 million flows to Linear Networks and Content Sales/Licensing, we have ~$7.3 billion of free cash flows. At 12x FCF (or 8.4x EBITDA), the two businesses would collectively be worth $87.6 billion.

Unallocated Shared Expenses

Lastly, Disney reports corporate and unallocated shared expenses for corporate functions, executive management, and certain support functions. These are not captured within the segment reporting and amount to ~$900 million per year ($860 for the TTM, $817 million for 2020, $987 million for 2019). If we assign a 6x multiple to that, we have $5.4 billion of value drag.

Bringing It All Together

So, as sum-of-the-parts, we have a present value of $108 billion dollars in DTC which comes with a wide range of possible future outcomes, a more stable present value of $66 billion in Parks, Experiences, and Products, and a less stable present value of $87.6 in Linear Networks and Content Sales/Licensing. Subtracting the value drag of $5.4 billion from unallocated shared expenses, we have a total value of operating assets of $256.2 billion. Then, subtracting interest-bearing liabilities of $55.8 billion and non-controlling interests of $9.5 billion (as per Q3 2021), then adding cash of $16.1 billion (as per Q3 2021), we have $207 billion in equity value, or ~$114 per share. Given that the stock closed at $171 per share yesterday, the current price looks a little like a leap of faith.

Sure, given the wide range of possible outcomes around DTC and the possibility that the bleak outlook given for Linear Networks turns out wrong, we could find a way to justify the current price but it would require me to stretch my assumptions more than I am comfortable with. For one, a 12x FCF multiple assigned to the collective Linear Networks and Content Sales/Licensing isn’t that punitive. (AMC Networks currently trades at 7.4x TTM P/E while Discovery trades at 11.9x).

We weren’t exactly punitive in valuing DTC either. For one, we assumed that ESPN+ and Hulu would be able to sustain the same annualized retention rate as Disney+ of 70%. Secondly, we assumed that the DTC bundle would be able to sustain annual price increases of 5% even as a large part of the net subscriber growth will have to be found outside of North America. Thirdly, simply increasing the growth rate of the CAC from 3% to 5% over the next ten years would lower the value of the operating assets for the entire business by $20 billion. You could argue that the total subscriber count could grow beyond 600 million subscribers by the end of 2031 but whether it will I think is anyone’s guess. It pays to remain conservative.

Furthermore, I don’t buy into the possibility that Linear Networks can sustain its level while DTC grows immensely. So for Disney to justify its price, Disney+ and the rest of the bundle will have to be hugely successful. Yes, Disney owns better enough IP than almost any other competitor to be able to pull it off, but there’s not much room for error. If streaming stumbles at all, even the best of Disney’s businesses probably won’t be able to offset that disappointment.

Disney is a remarkable company with an incredible brand, but I find the stock a pass for now. At this price, the pari-mutuel system just doesn’t put the odds on our side.