Back in September 2022, it was announced that Adobe would be buying Figma in a $20bln half cash, half stock deal. Not only was it going to be the biggest acquisition in the company’s history, comprising 13% of the company’s own market cap, but at 50 times forward ARR and 100 times trailing ARR, Adobe would also be paying one of the highest prices ever for a SaaS firm.

The market did not take the news lightly. On the day of announcement, Adobe stock dropped 17% and continued falling for several days until it finally recovered after months. You would think, then, that shareholders would find salvation if regulators were to try and block the deal. Well, not exactly. Last month, on Feb 24, when the news broke that the DoJ was preparing to block the deal, the stock again dropped almost 8%.

Empathy for the existing shareholders is warranted. Evaluating the deal is a tough one and perhaps calling it “reaching for valuation” would be an understatement. What’s going on? Why would Adobe, the once untouchable design software monopolist, pay such a high price for a company that seemingly did the same thing as Adobe’s own XD product? To get the human capital? To merge Figma with the Experience Cloud business? Or to simply get a market challenger out of the way before a bigger whale (I’m thinking Microsoft) scoops it up?

If the latter would be the case, this might be your evidence that Adobe’s moat isn’t as impenetrable as once seen. I have reason to believe that this, in fact, would be the case, and in this write-up, I’ll argue why that is. But first, to get a measure of Adobe’s decision, you would also have to understand the company’s path to its current position.

Adobe’s History

As every Silicon Valley storyteller expects you to believe, the one place where startup idea flourishes is the architectural symbol of the garage. Well, Adobe actually did start in a garage—John Warnock’s garage—in 1982, and the company’s first logo was designed by Warnock’s wife. While named after Adobe Creek in Los Altos, Adobe is also Spanish for “Mudbrick”, alluding to today’s creative nature of the company’s mission.

As their first invention, Warnock, together with co-founder Chuck Geschke, created PostScript, the first international standard for computer printing that paved the way for the desktop publishing industry in the 80s. It was such an important invention that at the outset Steve Jobs attempted to buy the entire company for $5mln. Instead, the two founders let him buy 19% of it including a five-year license for PostScript in advance, making Adobe the first first-year profitable Silicon Valley company in history at the time. Evidently, Apple Computers became Adobe’s most important customer.

After PostScript, Adobe developed proprietary digital fonts in the format they called Type 1. Then, when Apple followed suit and developed a competing font standard by the name of TrueType, which was fully scalable and gave precise control of the pixel pattern at the font’s outlines, Apple and Adobe started competing in Adobe’s tight space.

It took a break in the mid-80s with Steve Jobs, after he sold his Adobe stake, to diversify the company’s offerings and find the company’s path to the design mastodon it is today. Ironically, when Adobe released Illustrator, a vector-editing program, it was designed exclusively for Apple’s Macintosh. Invented on the company’s font-development software, Illustrator significantly helped popularize PostScript-enabled laser printers, creating a feedback loop that made Illustrator ever popular, spurring a growth rate of >100%/year in Adobe’s first 7 years of operations until the end of the 80s. By then, Adobe introduced what was to become its graphics-editing flagship software by the name of Photoshop.

Then came Premiere in 1993 and Adobe slowly began to dominate the market for creative software. In that same year, Warnock launched a paper-to-digital revolution idea that he called “The Camelot Project” in which the goal was to enable anyone to capture and share documents from any application and print them on any machine, entirely digital. That project became the PDF, the Portable Document Format. As ubiquitous as the PDF format is as an international standard today, its trajectory wasn’t a straight line. Adoption in the early days was slow and Adobe’s board wanted to kill the project. The original version of the PDF had no support for hyperlinks, its larger size compared to plain text files required longer download times over, at the time, slower internet speeds, and even rendering a PDF was a hassle on the low computer power of the early 90s. It was only when Adobe began distributing its Adobe Reader for free that things started picking up and it particularly picked up with one specific target group: the IRS. When the IRS started using PDF to digitize tax filings and began distributing tax forms digitally as opposed to physical mail, PDF adoption went from there.

From the early 90s, Adobe embarked on a series of acquisitions including OCR Systems, LaserTools Corp, Compution Inc., Frame Technology, Ares Software, and Aldus that added PageMaker, After Effects, and the TIFF image format to its product line. But one significant acquisition that squashed all previous acquisitions combined occurred in 2005 when Adobe bought its main rival, Macromedia in a $3.4bln all-stock deal, primarily to add Flash to the portfolio. (After living high on Flash for a while, once logging over 1 billion installations worldwide, Flash’s closed nature failed to live up to HTML5 internet developing standards, was excluded from iOS in 2010, ended its support for Android in 2011, and was officially deprecated in 2017).

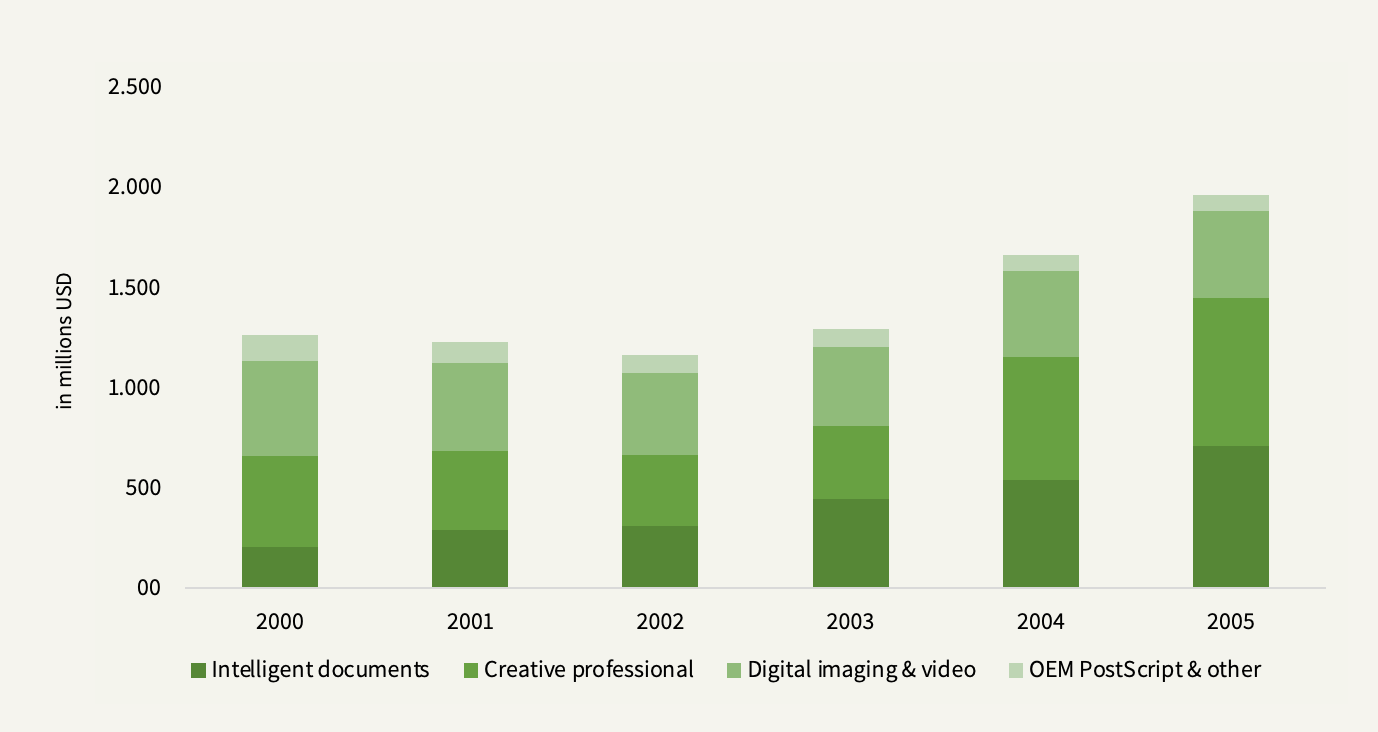

Despite all efforts to branch out, with an integration here and there, by the mid-00s it was evident that Adobe’s business was coalescing around its creative applications and document (PDF) business.

And the same was the moat. During this period, Photoshop et al. had become the de facto standard in digital design. Whether you were editing a photo, making a poster, or designing a website, it happened in Photoshop. Photoshop had not only become a brand but a verb too (“that pic looks Photoshopped!”), which, if you think about it, is a remarkable feat for a software product considering the obsolescence risk software generally faces as newer and better software enters the scene, or worse, as customer needs change (which I’ll get back to). But brand value isn’t the only thing that lies behind its success. As “designer” had become more than just a fashion profession but someone that every company on the Internet needed, network effects came in as designers using Photoshop compelled more designers to use Photoshop which in turn made new and aspiring designers require companies to use Photoshop before applying for a job (Adobe smartly distributed its software for free to schools and universities, defending this network effect moat). And, as other use cases became important, such as video, audio, or webpages, Adobe offered software that looked and felt similar to Photoshop (the learning curve on creative software is generally high), locking the customers in the ecosystem.

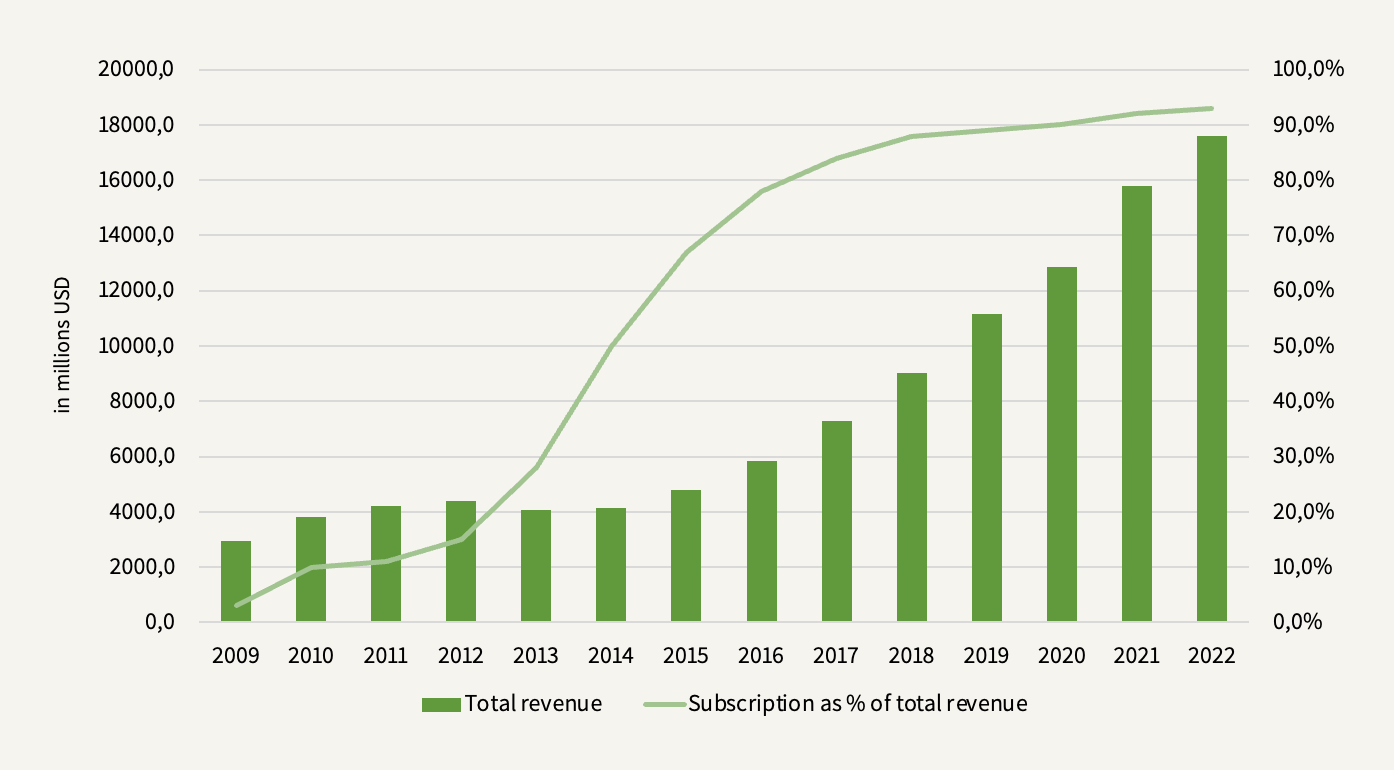

When Shantanu Narayen took over as CEO in 2007, that’s when Adobe really took on the transformation into the company that we know Adobe as today. Narayen is a leader who’s made some bold bets that have paid off. One of the big ones was to take a high-ticket (the entire Creative Suite went up to $2,600 per perpetual license in 2010) monopoly business and courageously change it to a lower-priced SaaS model.

Under its traditional perpetual license model (by selling those shiny DVD discs that you used to prop into the computer to install a program), Adobe sold to the customer once and that customer could continue using the program indefinitely, unless, of course, Adobe would come out with an updated, better version every few years and the customer would want the newer version. Narayen saw fit the still-infant subscription revolution and decided to push Adobe in that direction big time, shifting the entire Creative Suite to what’s now the Creative Cloud (CC). At the date of announcement in November 2011, the stock price dropped 6% and took months to recover. (The market always seems to punish bold moves). For the subsequent three years, Adobe ran the Creative Cloud and the perpetual licensing model in parallel and then completely shut down the latter in 2013.

The initial goal was for CC to reach 4mln subscribers by the end of 2015 (by comparison, the perpetual licensing was stuck at 3mln units). But in the always-so-obvious rearview mirror, even management guidance is sometimes no better than anyone else’s qualified guess. CC instead ended 2015 with 6mln subscribers, off the mark by a couple of million. Management found that they had significantly underestimated the huge untapped market waiting to be seized from the SaaS model. As the transition went on and that untapped market kept growing, revenue growth went on a wild ride:

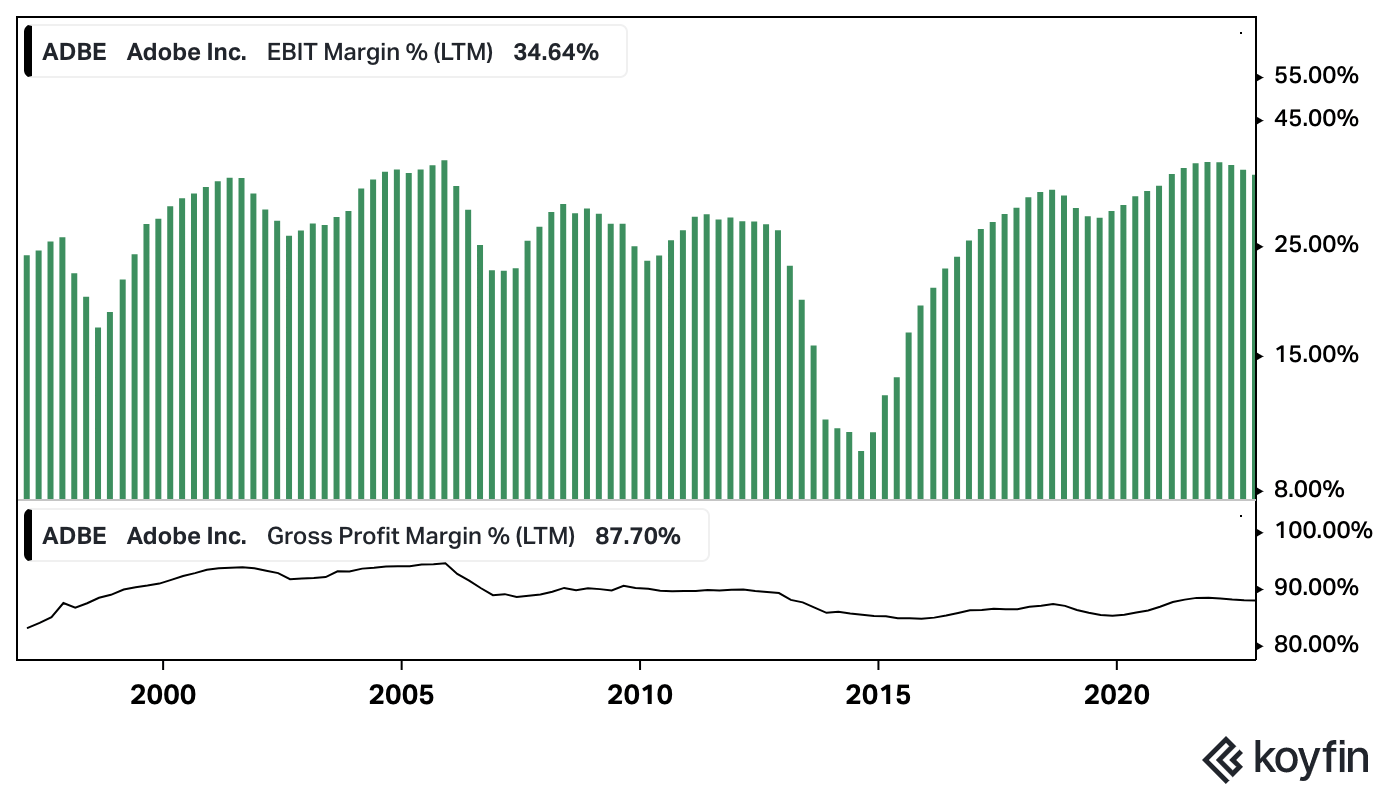

To emphasize the courage it took to shift Adobe’s entire revenue model, consider the hit margins took immediately following the shift and how it went to new highs post-2017:

To explain the fact that operating margins now seem to float at a higher normalized level, you could say that cloud computing costs are negligible to the legacy distribution costs Adobe used to incur, but then you would also have to factor in the difference in CAC between physical and online distribution. The former, roughly speaking, is the difference between the wholesale price to distributors and the retail price (explaining Adobe’s higher gross margin pre-2012) while the latter depends on Adobe’s S&M efforts and CAC. Difficult stuff to untangle. But what we can conclude is that what really drove the margins up to a significant degree have been: 1) a larger customer base to divide fixed costs, and 2) higher LTV from that customer base.

The latter is interesting because it determines how smart the SaaS transition was. As I mentioned earlier, the entire Creative Suite went for $2,600 under the perpetual license model. At the outset of the SaaS model, Adobe priced the entire CC at $600/year which means that Adobe would be sure to at least retain every subscriber for a minimum of 4.3 years to make the two models a wash. Adobe, shamefully, doesn’t disclose unit economics, but given the fact that management back in its 2014 earnings call stated the retention rate to be north of 80%, you could be looking at a possible LTV north of $3,000/subscriber. Meanwhile, retention rates are likely to be different between individual licenses and enterprise licenses (with the latter higher given its professional use case), which may bring the average LTV even higher due to the enterprise license’s higher price point of $840/year per seat.

What’s interesting is the fact over the past decade, Adobe has only raised these prices by 10% and ~21%, respectively, to $660/year for individuals and $1,020/year for enterprises today. I see two possible reasons for that: either 1) Adobe wants to keep growing the installed base as rapidly as possible at a low price point with imminent price increases later, or 2) Adobe has in fact hit the price at which retention and LTV/CAC is at optimum and further price increases above inflation would be profit-minimizing. Either way, Adobe’s envious operating margins are a testament to some historical form of pricing power. The question is from here, they either have a price lever to pull or they don’t. One thing’s certain: the company valuation can swing widely whether it’s one or the other. Our conclusion on this issue might be answered in the following section.

Enter Competition

Stepping back, big picture, Adobe first invented the best creative applications used by designers, then lived high and mighty on its monopoly for decades, then found out it had a huge untapped market for a target group that wouldn’t pay a high-ticket price but surely would pay a lower monthly price, and then rode that wave for another decade, gushing out free cash flow on the way up.

But the story going forward is likely not going to be that easy. A lot of the tailwind that Adobe experienced with the SaaS transition had to do with the world entering the golden age of design where everybody wants to express themselves and there are lots of disrupters that want a piece of that cake. Today, Adobe faces remarkable competitors that are a lot more apt to challenge Adobe’s power. In a way, the SaaS and cloud revolution has been both a blessing and a curse for Adobe. As the SaaS transition surprised to the upside in terms of TAM, that also brought unforeseen consequences in competition from below.

Even worse than increased competition is when that increased competition is coupled with changing customer needs or when customers do like the incumbent’s products but think they aren’t perfect, or I mean, aren’t exactly ideal. In such situations, the incumbent monopoly may resist changing its core offering to the new use cases since it’s not only costly but also risky to change a thing that historically has worked so well. Then other players are quick to swoop in, find the incumbent’s weak spots, and attack.

First to challenge the Adobe monopoly has been Canva with its atomic concept around components and templates. Whether users wanted to create a cover image for LinkedIn, a wedding invitation, or an ad creative, Canva was committed to making that as easy and fast as possible. Canva combined the best qualities of enterprise software (simple templates) and social media (intuitive design tools) and then rolled out an ecosystem by creating marketplaces and communities around its templates, layouts, and fonts. The second-order effect of this “tool for non-designers” model was that some companies went ahead and skipped the designer job altogether. Some include big accounts. Canva says that 85% of the world’s 500 largest companies are using its platform. Marriott uses Canva Enterprise to promote hotels across its dozens of different brands. Live Nation uses it to coordinate promotion between artists and venues. Canva democratized design and this product-market fit crystallized in explosive scale from $3mln dollars of seed money in 2012 to today a whopping >100mln monthly users and a $40bln valuation at the last financing round.

Obviously, there are trade-offs between ease of use and functionality. For instance, you cannot use Canva to free draw since that would put non-designers off and the entire business model is built on not intimating users. Canva couldn’t replace designers and their specialized [Adobe] tools, but it could work alongside them by removing small, irksome design needs.

But then came Sketch, a vector-based platform akin to Illustrator built primarily to craft entire digital products and interfaces. Like Canva, Sketch exploited the fact that Illustrator was intimidating to newcomers and simplified the interface to attract a following of design enthusiasts who had actively turned their backs on the bloat and complexity of Adobe’s suite. That following went up substantially in 2013 when Adobe decided to discontinue its development and support for Fireworks, its bitmap and vector graphics editor, which had a considerable user base, many of whom had used the tool since it was originally part of Macromedia. When those users were abandoned by Adobe, many migrated to Sketch which could do everything better and faster. By around 2015, Sketch was seeing mass success, not only as a cheaper alternative to Illustrator, but also because they understood what designers actually wanted: fewer, yet highly specialized tools built for larger complex projects rather than specific isolated designs. When Adobe said, “Let’s put as many features as possible into Illustrator; more is better, right?”, Sketch said, “Bloat is something we want to avoid at all costs.”

But however innovative and smart Sketch was, it slept on its laurels. While Sketch clearly appealed to designers’ need to work on complex projects vs. one-off designs, it failed to recognize that such projects often require working in teams. Rather than designing in isolation, Sketch users worked in collaborative groups of a larger process.

Figma became what Sketch could have been and changed the ballgame due to two important factors: it was browser-native and solved designers’ need for collaboration. Figma recognized that the design process shouldn’t be seen in isolation but as an integral part of every other division involved in product development. And the first step to solving that problem was to remove the frustrating logistical frictions that would occur whenever an organization wanted to include non-designers such as engineers, or even the CEO, in the process. In order for a non-designer to access a working design, they would need to download the current file and have the appropriate program installed, which was costly and difficult to justify for those who didn’t work with it on a daily basis. Additionally, the complexity of these programs made them unwieldy for non-designers to navigate, and feedback had to be given in separate communication channels. Even worse, if a designer updated the file before the non-designer had finished accessing it, the file would be out of date without them knowing it. For designers, sharing designs with non-designers in the organization meant handholding them through the process, resulting in a slow feedback loop. As a result of this friction, non-designers often disengaged from the design process, leading to an inefficient organization and a frustrating experience for all involved.

So, Evan Wallace, Figma’s founder, made a very smart move. Whereas incumbent players were stuck to their cloud-first product setup, Wallace would take advantage of new technologies such as WebGL, Operational Transforms, and CRDTs to make Figma completely browser-first. It’s hard to overstate how important that was. As a browser-first product, there would be no files and no syncing needed with others to work on a design, paving a way for non-designers to be involved in the entire design process. Not only could designers work together on the same projects; but they could also do it at the same time. And as was the problem with cloud-native products, there would be no conflicts (and finally no more obscure file names to give the eighth final draft in the shared folder). Sharing a working design with a non-designer would only require sending a link. The non-designer could provide feedback without disrupting the flow. Even better, they could watch as the feedback was being implemented in real-time.

Furthermore, as Figma wanted to go from product to platform (as they all do since the big money is in creating an ecosystem), the browser-first approach was again an advantage. By focusing heavily on plugin creation, Figma turned designers into developers by enabling them to remove repetitive or tedious tasks and automate not only their own workflows but also the workflows of others. Using these plugins would be instantaneous: click once and the desired function is instantly applied to the project. Compared to Sketch’s and Adobe’s plugin systems that required downloading and uploading, Figma’s platform approach felt effortless.

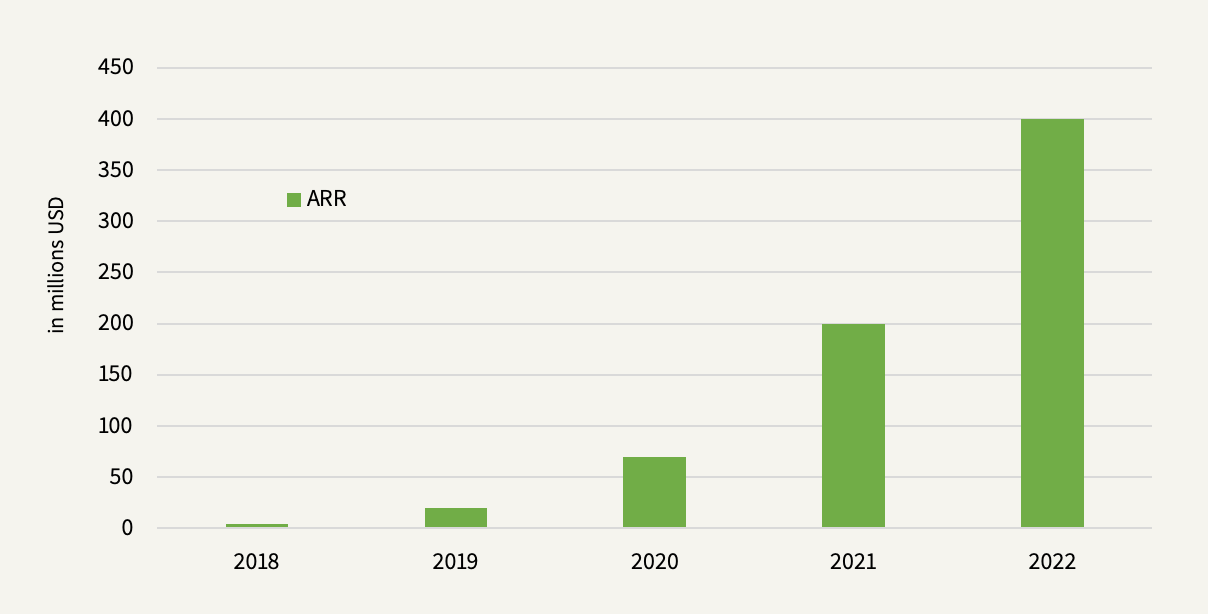

There’s an important mental model that applies to Figma’s story: technology has its way of changing so consistently that possible disruption inevitably props up every once in a while. Steve Jobs called this Technological Windows of Opportunity. Figma won because it flipped the distribution loop by taking advantage of new web-dev technologies that allowed a highly complex piece of software to be run fast and efficiently entirely on the browser and created a level of collaboration that was previously unthinkable. With no technical debt to bog it down, Figma got a first-mover advantage to gain enormous traction and a quasi-religious following with designers and non-designers alike. The evangelists bringing in other users wouldn’t only be designers convincing other designers but also non-designers convincing other non-designers. Or!, even non-designers convincing other designers. Or!, even non-designers convincing the CEO. This cross-sided network effect spurred its hyper-growth story:

To Adobe’s credit, the company wasn’t exactly caught off guard by these competitors. Adobe created Adobe Express, a free, browser-first tool built for lightweight tasks with a huge stock of over 175 million images and over 20,000 Adobe fonts. Express was a smart move since it acts as a top-of-funnel lead gen machine that Adobe now upsells from. And before you say, “well, better late than never”, when you read that it was first launched in December 2021, consider the fact that Express has already exceeded 43mln users, almost half of Canva. Meanwhile, Adobe is currently jumping further on the browser train by building Photoshop Web, Illustrator Web, and Acrobat Web, all of which will be offered as freemiums with limited functions.

As for Figma, Adobe’s most comparable fighter was Adobe XD, but again, that wasn’t built for the browser, and it doesn’t take long to figure out that XD wasn’t nearly as competitive a product as Figma. Just spend a couple of seconds searching for “Adobe XD vs Figma” and you will find many arguments and YouTube videos as to why Figma is better built for designers, many of which I already discussed above. So there you have it: the reason why Adobe is now acquiring Figma in what is probably the most expensive SaaS deal in history is that it’s that big of a threat to its monopoly and Adobe is paying whatever it takes to keep that monopoly. I suspect management hadn’t even concluded beforehand what they would do with Figma once they bought it. On the recent Analyst Day, management did say they could take Figma, Express, and Acrobat and create an entirely new platform based on all three but how that is going to play out is up for question (and perhaps sounds a bit like window dressing?).

Adobe Valuation

Welcome to capitalism. In a true Innovator’s Dilemma where new technologies cause great firms to fail, competitors find shortcuts all the time, and incumbents either freeze or pay up to get them out of the way. As you can tell, forecasting the future of creative software is not a bit easy, even as it may look like you have a durable moat in front of you. That’s why, even as Adobe’s historical financials have been remarkably steady, I find it impossible to value the company to a tee. But I’m at least going to ballpark it. At the end of this write-up, I have added my model for you to download so if you disagree with any of my assumptions (as you certainly will) or want to test scenarios, you can do so.

Since Adobe’s Figma acquisition is still pending, I thought it would be constructive as well as an interesting exercise to value the company under the scenarios that Adobe does or doesn’t close the deal. Of course, that would require me to forecast most notably: 1) the future of Figma’s hyper-growth story, 2) how management expects to integrate Figma, and 3) to what degree Figma could entrench Adobe’s moat if the deal doesn’t go through, all making the valuation exercise not a bit easy.

Adobe Doesn’t Acquire Figma

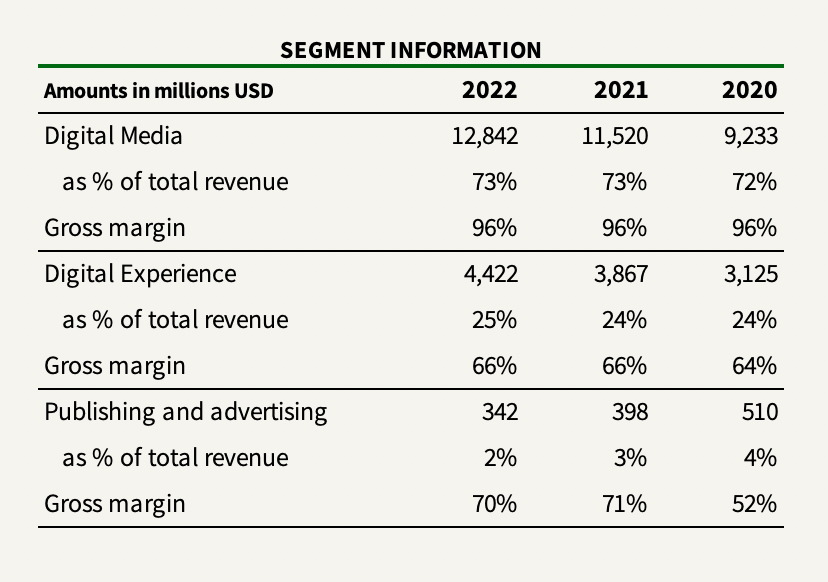

If we start with Adobe without Figma, the company has segmented into three lines of business today:

- Digital Media

- Digital Experience

- Publishing and Advertising

I know this write-up has focused extensively on the Digital Media segment since it’s the most important, comprising 73% of revenues and likely >100% of Adobe’s FCF. However, Digital Experience is also important to the valuation since it’s growing quickly (14% in 2022 and 24% in 2021) and Adobe keeps throwing money at it.

Basically, Digital Experience came out of management’s vision of using its data and creative monopoly to capture more of the value chain of its enterprise customers by cross-selling marketing and analytics solutions that “allow businesses personalized experiences for every single customer”. Rather than just enabling people at the front end of the creative process, Adobe’s aspirations with Digital Experience are more than that; They wanted a role to play in how businesses manage and monetize all of their content. From the FY2022 earnings call:

When you take even the larger companies, they are all trying to get a handle as they engage digitally with customers. How much content is being created? Where is it being created? Where is it being delivered? How do we localize it? What’s the efficacy of that content? And so, I think this content supply chain and everything we have with our creative applications, our asset management, the fact that we then deliver that content, I think we continue to believe that that’s going to be a growth driver for the entire business as well.

Adobe jumped into this business largely through the acquisition of Omniture in 2009 ($1.8bln) and has kept building on the platform through tuck-ins. In 2018, two of the large ones include Marketo ($4.7bln), B2B marketing and engagement software, and Magento ($1.6bln), an enterprise commerce platform that most notably competes with Shopify Plus. Digital Experience takes up 67%, or $8.5bln, of Adobe’s total goodwill and I think you can expect more money thrown at this business for several years. Again, shamefully, Adobe doesn’t disclose much segment data below the gross profit line so it’s hard to tell how’s it going. It’s worth considering that Digital Experience will fight tougher competition (although oligopolistic) in this space including but not limited to Google, Salesforce, SAP, and Shopify. On the other hand, the Digital Media and Digital Experience segments are complimentary and likely more than double maybe even triple Adobe’s TAM, so I think management is smart to take that bet. That said, much of the value here is going to come down to management’s capital allocation skills and whether the return (currently likely to be nil) on invested capital (∼$11bln) is going to be value-accretive over the long term as the segment scales to better compete with the rest of the oligopoly.

Lastly, Adobe’s Publishing segment comprises a bunch of legacy products such as e-learning and other inconsequential activities that have decreased by 33% in revenue from two years ago to comprise 2% of the business today.

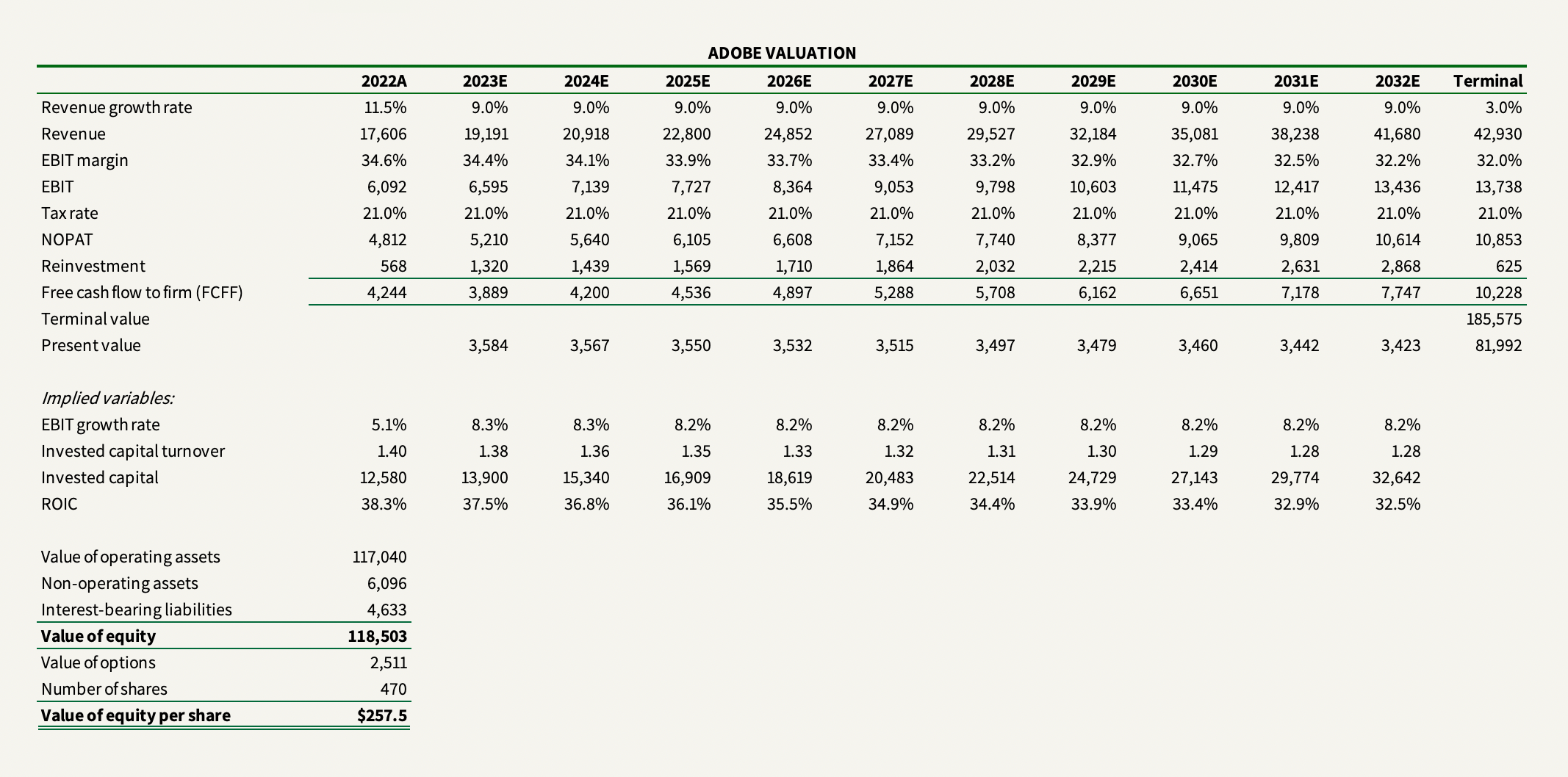

My valuation story can be broken down into the following components:

Revenue: If you want to put a correct estimate on the TAM for both Digital Media and Digital Experience, you might as well put a finger in the air. Even Adobe couldn’t quite grasp the market potential it would encounter ten years ago. The TAM could be 10 times bigger than Adobe’s revenue or it could be 30 times bigger x years into the future. It’s obviously an important number since it could determine whether there’s enough cake for everyone even as competition increases, but determining growth as a function of TAM, and not the other way around, may set us up for trouble. Given that we now look at Adobe ex-Figma, I’m going to assume high single-digit growth in revenue over the next ten years as a mix of market expansion plus a bit of pricing power, basically giving Adobe the benefit of the doubt that they will retain market share. It should be noted that APAC comprises <16% of total revenues so even if Adobe would have little pricing power, it might pick up on an extra point or two there.

Profitability: If we were to incorporate competitive forces into forecasting Adobe’s future profitability, how might that play out? For one, you would most likely see increasing S&M expenses as a percentage of revenues since retaining an >80% retention rate or ramping up gross customer acquisition to make up for the lost ones would require a bigger marketing budget than Adobe might be used to through what has ostensibly been pure maintenance spending in Digital Media. Meanwhile, since we don’t have Adobe’s cost structure by segment, we don’t know the exact S&M share of revenues at Digital Experience, but I could imagine that going up in the short term too, however more than offset by increasing returns to scale so that the Digital Experience business will move into something like the average of Salesforce’s and SAP’s pre-tax operating margin of high single digits (otherwise, what’s the point?). Likewise for R&D, disrupters like Figma will likely pressure Adobe’s R&D spend as we already see with Adobe working to go the browser-first route and probably is working more on product development than they ever have. For the past two years, the R&D spending has increased by the same rate as revenue, remaining at 18% of revenue, but if growth stalls a bit as I expect as per the revenue discussion above, I don’t expect growth in R&D to slow down to the same degree, therefore increasing as a percentage of revenue. All in all, the counter-effect of decreasing profitability in Digital Media and the increasing profitability in Digital Experience, with the latter likely to grow faster over the next ten years, has me assuming Adobe’s overall pre-tax margin to come down slightly from its current 35% to something like 32% in the mid-term.

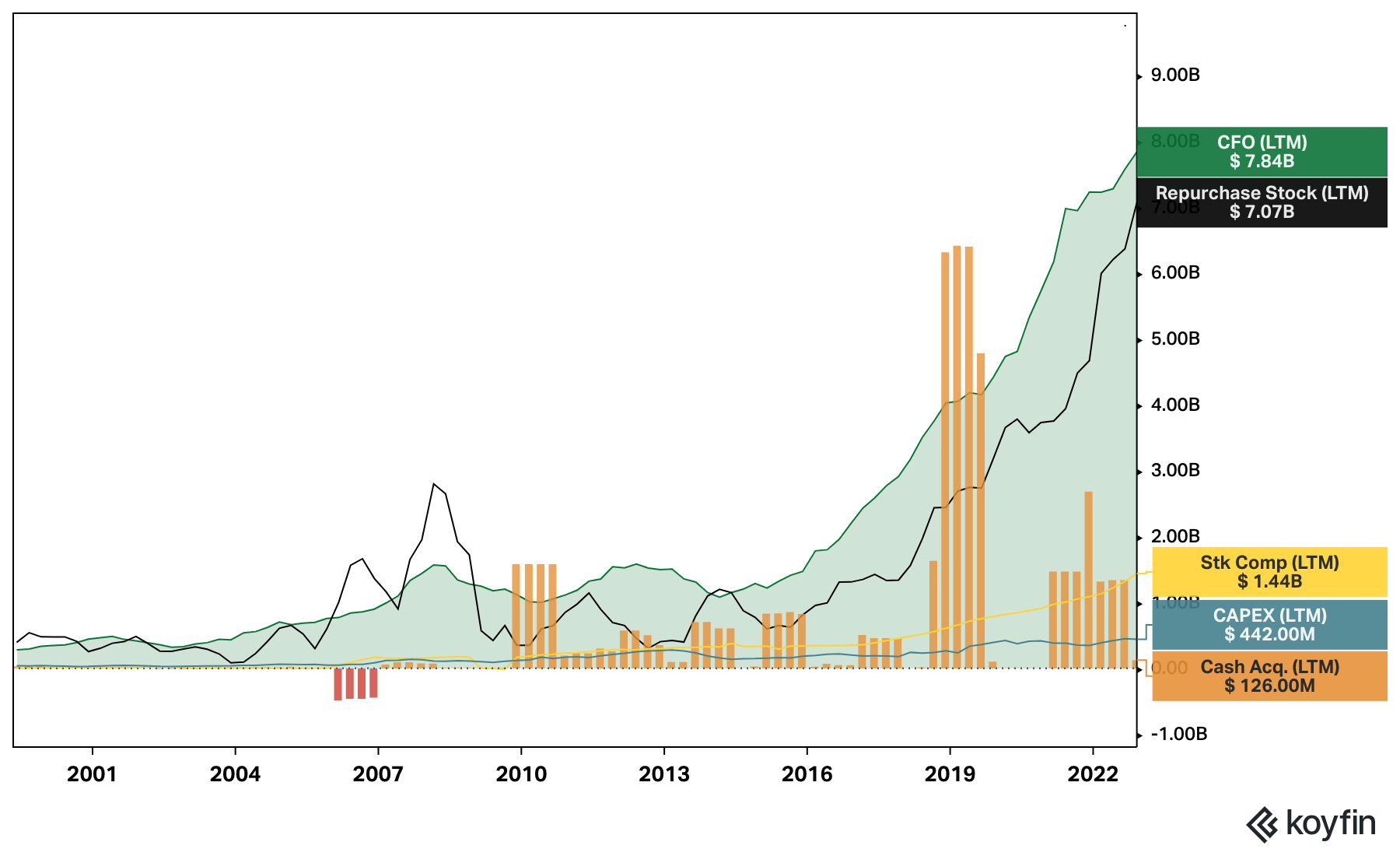

Reinvestment: Here it’s important to distinguish whether you want to treat S&M and R&D as pure expenses or take out the growth part of the spend (which would be all of R&D) and treat it like capital investments instead of the conventional (and wrong) accounting method as expenses by adjusting the financials. The reason I mention this now is that it’s an important question to get right when 1) you want to compute a company’s true return on invested capital which I explain in this article, and 2) you determine the company’s future reinvestment since there’s a risk of double-counting the effect depending on whether you have chosen to capitalize the expenses or not. In this case, as per my profitability discussion above, Adobe’s prospectively higher R&D expenses are expected to hit profitability and therefore we do not treat them as reinvestment. Hence, Adobe’s reinvestment needs for the purpose of this valuation will only be pegged to those that are required in fixed assets and acquisitions. One of Adobe’s historical advantages has been its ability to grow with relatively little fixed capital investment (fixed assets turn over 8 times per year) and a negative cash conversion cycle. However, as I mentioned before, Adobe has relied considerably on acquisitions in growing the Digital Experience segment which I assume they will continue to do in the future. Growth by acquisition may even be turned up a notch within Digital Media too to fend off competition. For the past three years, the sales-to-capital ratio has averaged 1.2 and I’m going to remain that a marginal constant in the mid-term with a ramp-up to 2 as growth stalls.

Using a 10% opportunity cost of equity capital and a 4% cost of debt weighted by Adobe’s current capital structure of 33% total debt/equity, the summary of my assumptions is included in the following valuation:

Now let’s look at the scenario in which Adobe acquires Figma, a relative contributor to my cloudy view on Adobe’s growth and future profitability.

Adobe Acquires Figma

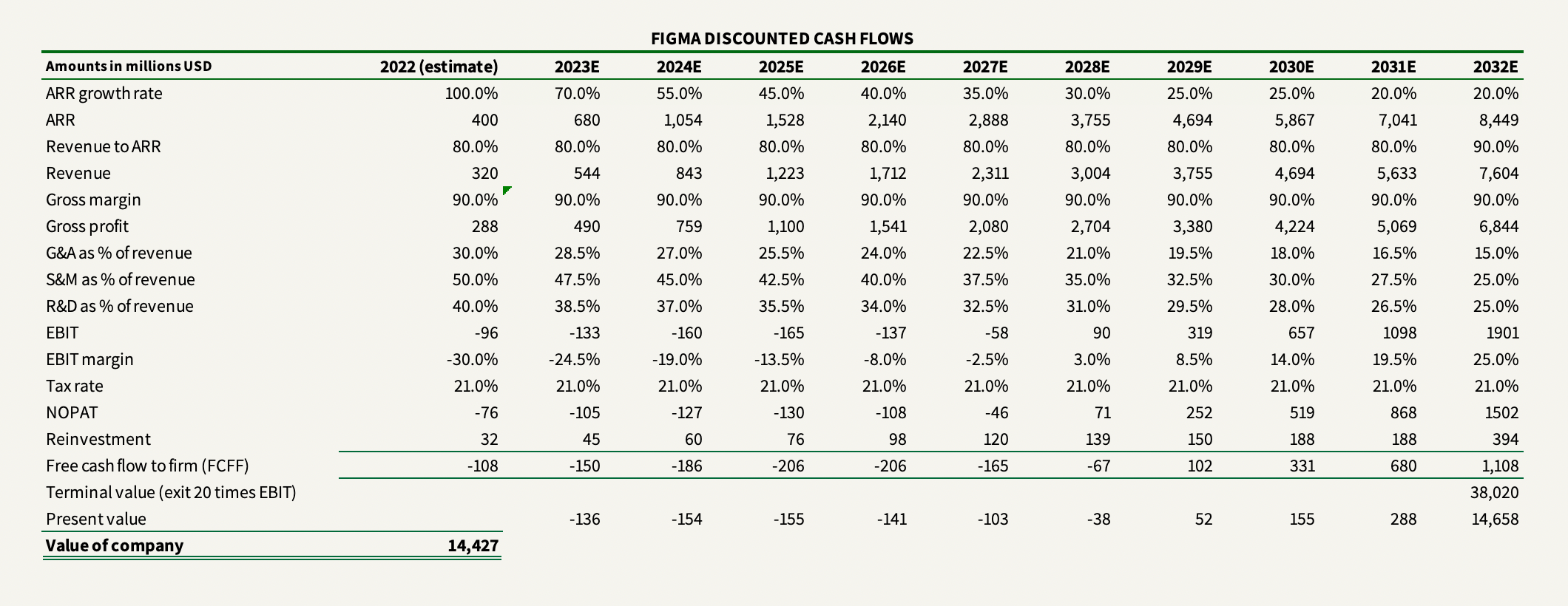

The balancing act you face when doing a valuation is the ever-present struggle of trying to be right while not getting ahead of yourself. In many cases, that means erring to the side of caution and opting for conservative estimates. When looking at hyper-growth companies, you can imagine how difficult that is since the growth you assume even just a few years out is so important to the thesis and the terminal value that lies in the end. Given the price Adobe is willing to pay for the business, the future growth prospects of Figma are obviously optimistic but extrapolating the previous years’ >100% growth rates is likely also to be stretching it too far.

The valuation exercise isn’t at all made easier given that the financial information we have on Figma is extremely limited. All we have to work with is the following statement by Adobe at the time of acquisition:

[Figma] is expected to add approximately $200 million in net new ARR this year, surpassing $400 million in total ARR exiting 2022, with best-in-class net dollar retention of greater than 150%; gross margins of approximately 90% and positive operating cash flows.

Bear with me here. That information is not enough to build a valuation that’s reliable of any kind. But my purpose here isn’t really to get the value of Figma right; it’s to see what kind of expectations I would be comfortable projecting Figma financials against to gauge whether Adobe’s $20bln purchase price is even within the realm of sanity.

Revenue: Starting with growth, we first need to decouple ARR and revenue which are not the same thing. As a growing subscription business, ARR would be higher than revenue since a lot of the added ARR would come during the year. The higher the growth, the wider the revenue-to-ARR ratio. During Figma’s current high growth phase, I assumed the ratio to be 80%, rising to 90% in ten years. Then I assumed ARR to grow by 70% for 2023, quickly dropping 40% over the subsequent three years and then gradually slowing to 20% in ten years landing at ~$8.5bln ARR and $7.6bln of revenue in 2032. Those are big expectations but I’m somewhat relaxed about the prospects of coupling Figma’s competitive position with Adobe’s innovation and expertise, especially in 3D, video, fonts, and so forth. 2032 is far away, and if Figma continues spreading like wildfire among designers, that isn’t at all inconceivable.

Profitability: Now it gets harder. All we know about Figma’s capacity to turn a profit is its high 90% gross margin. What lands at the bottom we’re going to have to guess. I have a decomposed Figma’s cost structure into G&A, S&M, and R&D and assumed 30%, 50%, and 40% of revenue for each line, respectively, for 2023, gradually decreasing to 15%, 25%, and 25%, respectively, in 2032. Again, you can play around with these numbers yourself in the model (at the bottom of the write-up). My assumptions derive from the fact that I assume Figma currently earns a -30% pre-tax operating margin which will gradually go up to 25% in ten years.

Reinvestment: Since we, like with Adobe, look at Figma’s R&D and S&M spending on an uncapitalized basis, I’m going to assume that Figma’s tangible investment needs are extremely limited and likely has a net working capital benefit. I’m assuming a marginal sales-to-capital ratio of 5.

As for the cost of capital, I have assumed no debt and kept the opportunity cost of equity capital at 10%. Lastly, I have assumed a generous 20x EBIT exit multiple in 2032 which makes for an undiscounted terminal value of $38bln in 2032. Discarding cash and debt and discounting cash flows to today, that makes for a value of $14.4bln.

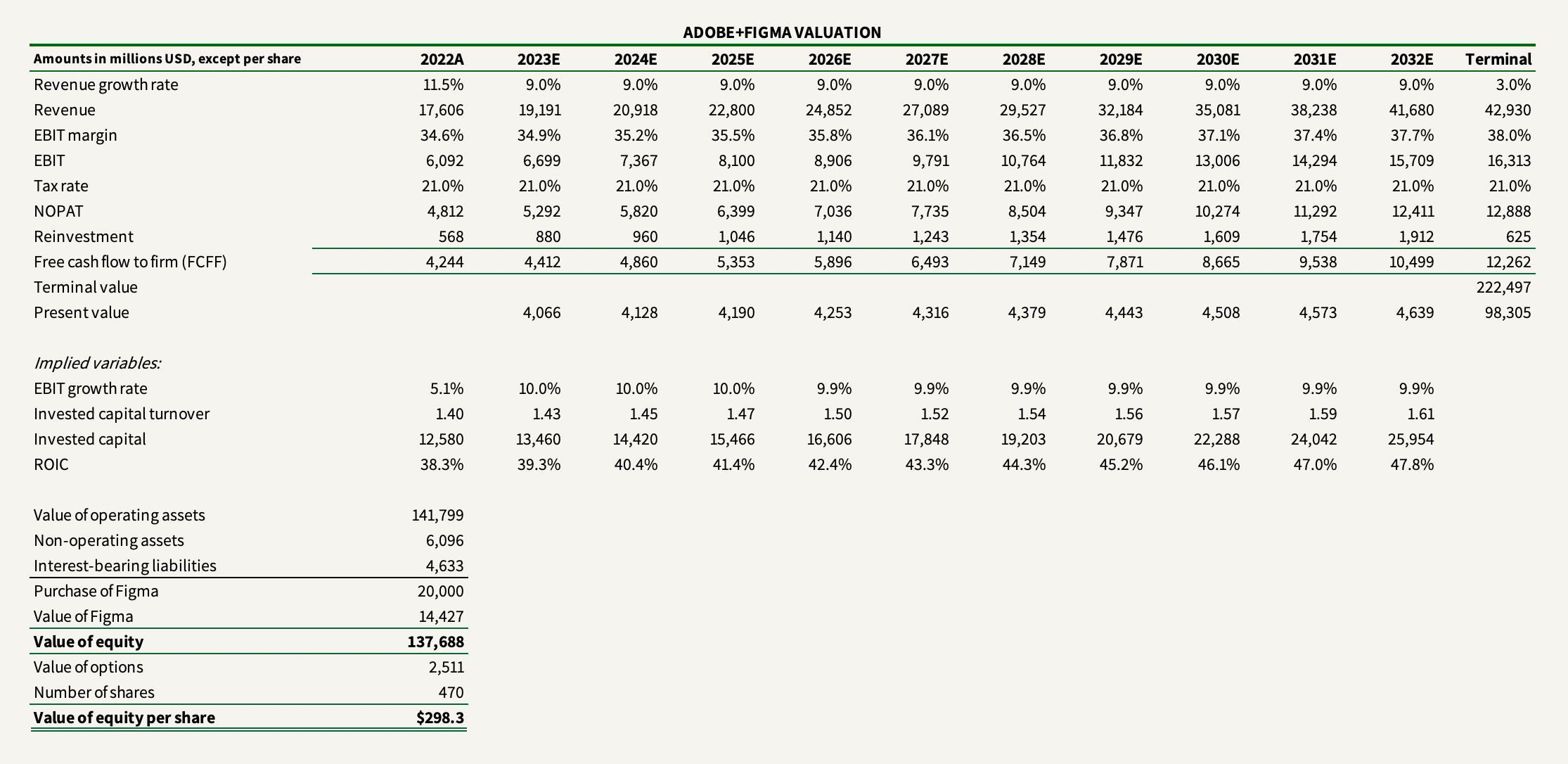

Since I can’t stretch my assumptions any further without losing sleep over it, that implies Adobe likely overpaid for Figma. But hey, that’s just looking at Figma. If we take out the $20bln purchase price in our valuation of Adobe, add Figma, and adjust my assumptions for Adobe’s revenue, profitability, and reinvestment (target EBIT margin of 38% and marginal sales-to-capital of 1.8) to reflect Adobe’s more dominant market position with Figma in the mix, we might get something like the following:

When a company acquires another at a price that may look out of this world, it’s important to think about its second-order effects. In my view, Adobe is worth more as a company if it acquires Figma, even at that $20bln price tag. On the other hand, note how the Adobe+Figma valuation depends so heavily on getting the competitive dynamics right.

Even though I haven’t done a sensitivity analysis on this valuation, I don’t have to. I already know that the possible values for Adobe swing wide. I’m not quite comfortable buying the stock either way. Honestly, even though this write-up was long, I’m the first to admit that I don’t know enough about this stuff and how the industry might play out. We often fool ourselves into thinking that knowing all the preceding facts and history gives us a crystal ball into the future. But that could be an illusion; a dangerous cocktail of sunk costs, chauffeur knowledge, and overconfidence. I’ve fallen prey to it many times and learned my lessons. Also consider the fact that I haven’t even mentioned the Metaverse, generative AI, and all those rapidly developing phenomena that remain to be seen how these next technological windows would affect Adobe… or Figma.