Welcome to my second annual letter on Junto.

After two years in the investing newsletter business, I’ve come to realize that this space was harder to break into than what I initially had planned in my head.

I started Junto at the best and the worst of times. On the one hand, the Internet Economy has allowed everyone with a little technical or persuasive skill to build a personal monopoly through the scale of the Internet and social media. By applying one’s own unique intersection of skills, interests, and personality traits, everyone can be known as a valuable thinker on a topic and open themselves up to the serendipity that makes putting out stuff online so special.

I thought creating an investing newsletter would be my sweet spot; a perfect intersection of work that allowed me with time to only read, think, and write deeply about companies and investing. And so I quit my job as investment manager at a family office to build my own personal monopoly.

But, of course, you can’t have everything. And this is where we get to the “worst of times” part. For the past couple of years, there’s been an explosion of high-quality content, competing newsletters, and a rapid increase in the pace of consumption. People, myself included, flip through one article, essay, or analysis after the next like nothing, inattentive to all the hard work and creativity that went into it because there are 100 other pieces sitting in Instapaper waiting to be paced through. I personally subscribe to many paid newsletters without the time to deeply engage with them or read even half of it.

Unless you constrain yourself to a very narrow topic—writing, for instance, only about FAANGs, SaaS businesses, semiconductors, LBO candidates, spin offs, etc.—it’s difficult to decorrelate yourself from others. And if you pick a broader category, there’s a large amount of social proofing involved where the most popular one gains the most followers. And there are various methods to gain popularity. There’s the shallow kind where you push hot stock tips, use catchy headlines, carefully time tweet threads, and whatnot, and then there’s the non-shallow kind where you exclusively produce high-quality content which has managed to catch on as the leading voice in that area. Either way, to grow, you’d have to stay top of mind of the reader, always pushing content to social media, doing outreach, and/or appearing on podcasts. How you market your offering suddenly takes up half of your time and your likelihood of making it while the quality of your content sits in the back. You find yourself stressing over how to get people’s attention rather than flipping rocks trying to find the best companies out there. When what I do is write deep content on a wide range of different companies once or twice a month, this has been a difficult hurdle to overcome. I’ve found that I have to spend an increasing amount of time on non-accretive activities, at least in terms of my investing goals.

So it’s been a hassle for me to balance the type of work necessary to make it succeed. There have been times when the stress of it has led to significant writing blocks and I didn’t feel like writing a damn thing. You see it somewhat in my email conversion rate of ~2%, which is quite unsatisfactory. The newsletter itself performs outstandingly (consistently >45% open rate) and I receive daily emails from subscribers thanking me for the content and wanting to discuss things further. But there’s this wall of friction. And I don’t blame the subscribers for not converting for the reasons already discussed. It’s content mania out there.

Now, I don’t want this introductory section of this annual letter to come off as regretful, that it’s impossible to earn a nice living from a newsletter, nor that it’s all about the money.

However, aside from the intellectual challenge, it’s somewhat about the money. As of writing this letter, Junto has 80 paying members and a little over 4,000 free subscribers to the Sunday Briefing newsletter. It’s nice, and I’m incredibly grateful for the members who’s hopped on the journey, but, of course, at an annual membership cost of $199/yr, it’s not yet enough to make a viable living.

I used to comfort myself with the notion that I was merely chronicling my own investing journey and that any member joining that journey would be a bonus in itself. As some of you know, the source of capital funding the Junto portfolio is my wife Julie’s and my jewelry company which we founded in 2015 when I had just started attending University and Julie was in high school. I’ve previously written about the ups and downs of the business. Fast forward to the past couple of years, it started to gush out comfortable free cash flow which we used to invest in a concentrated stock portfolio through our holding company and personal savings. The portfolio grew to a point where it became an equally important part of growing our wealth.

So there’s always been this cushion and notion that fully managing the portfolio was an important job in itself. But recently, I’ve started taking my opportunity costs seriously. My absolute passion is investing, investigating businesses, digging into balance sheets, and everything that comes with it, but I don’t like to play the game of theater, either by pushing shallow content down the throat of social media or by trying to over-intellectualize and complicate investing in order to sound smart and push through the endless stream of other newsletters that compete for attention. But I’m now aware of the fact that without spending a very significant part of my time on things other than research, it’s hard, if not impossible, to gain the necessary traction.

Where am I going with all this? I don’t know. I guess what I’m saying is that I’m contemplating whether my time and skills are better put to work in another intellectually stimulating environment that comes with benefits other than writing by myself while being a full-time marketer. I’ve come to appreciate networking a lot. Not only because you get better information by challenging your decision making from different angles of opinion but also because you open yourself up for more opportunities that you could not even imagine would come to you in the first place. It kind of makes me miss being a part of an intellectually stimulating environment with triangulating thoughts on a day-to-day basis. I’ll let you know in due time if I find another adventure to pursue.

It’s not like it’s all been sunk work so far. I’ve gotten to know many investors, writers, and value geeks all over the world—some I would now consider close friends—that I wouldn’t have gotten to know had I not started this business, which I’m incredibly grateful for. And the intellectual challenge has been very stimulating. Even as I haven’t made many investment decisions in 2021, I’ve evolved as an investor.

One thing I’ve learned is that many value investors are often anchored in their way of calculating stuff and reaching conclusions—that they must have a set idea of the correct value of a company. This is another way of saying that they focus too much on the numbers and less on the story. It’s an area in which I think I’ve developed the most, and one way you see it is in my company write-ups. In the early write-ups, I focused much on the numbers to build out the model whereas in some of the later ones, my thoughts on valuation have become more vague, taking up a couple of paragraphs.

Some of it has to do with how deep a company is within your strike zone. Developing a synthetic understanding of any company, no matter whether it’s boring or sexy, is a gradual process and you keep calibrating your conviction along the way. You can pretty much never value a company at a satisfactory level the first time you look at it. The sunk cost fallacy plays a big role here but it shouldn’t. It’s really only when you know a company and its ecosystem deep enough that you can appropriately build out a model without fooling yourself into a false sense of synthesis.

What goes without saying but must be said anyway is that you never buy a company’s past financials. You buy the (discounted) cash flows that the company will generate from now and during its remaining life. The past financials must be studied as an aid, but without a thorough, qualitative understanding of how a company has created and captured value, you don’t know why the numbers are what they are or what might cause them to break down, speed up, or inflect.

When you accept this lesson at your core, you learn that when you begin to study a company, the price shouldn’t matter to you because you cannot assess whether something you yet don’t know about is cheap or expensive based on simple multiples. And so instead of discarding multiple high-flyers like Adyen or Topicus right away, you start to explore your curiosity around the process by which the companies got to where they are and why they may be wonderful businesses. Which is a far more satisfactory way to approach the market. Keeping an open mind, that is.

So the natural extension of this approach is that you put the quality filter before the valuation filter. That way, you resist the problem of getting into what I call the “losing horse” problem where you pick the unfavorable horse because the odds look better. Oftentimes, it’s not difficult to assess who is getting disrupted and who is taking market share in the stock market. All else equal, you would naturally pick the latter as opposed to the former. However, the fact that the two companies may be far from equal on one key variable, price, the market’s pari-mutuel system turns an easy problem into a hard one. When a value investor stands between a company that they know faces a difficult hand as opposed to a better company at an, on the face of it, expensive-looking price, sometimes the price of the former is enough of a persuasion to buy it over the other. The reason why our minds persuade us into the losing horse problem is that we have a tendency to want to balance things out—that mean reversion will come in to make things right. But rarely is that the case. Oftentimes, you set yourself up for disappointment. It’s as true as Buffett explains: “It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.”

When you put the quality filter before the valuation filter, your explorative universe becomes bigger since studying any company, including the most expensive-looking ones, could provide you with valuable knowledge as you go on to study the next one. You simply start with ‘A’ and let your curiosity guide your intellectual journey. Meanwhile, your investable universe becomes smaller because you increase your hurdle the more you learn about different kinds of businesses. Your circle of competence starts to unfold, and soon you’ll find that fewer than 1-2% of the thousands of publicly traded companies meet your criteria while the other thousands don’t make the cut, valuation be damned.

So now, because you’ve restricted your investable universe down to a small pond, you may struggle to find compelling value in this pond. How could it be otherwise if it consists of the best of the best? The result is that you may need to be less demanding on the valuation filter and accept that valuations sometimes can get “a little silly”.

When you deal with a wonderful company, and this company truly turns out to be wonderful, what seems like a high price, maybe even a silly price, today may be proven to be perfectly reasonable in hindsight many years into the future because wonderful companies caught early tend to exceed expectations.

But whose expectations? The market’s, your neighbor’s, or your own? Sometimes, it’s everyone. Now, you may think that this idea incorrectly disregards the concept of intrinsic value and that if you buy above your own estimate of intrinsic value, you are a) either willing to accept less than your required rate of return or b) that you don’t trust your own analysis. But that’s not what I’m getting at. What I mean is that, sometimes, the intrinsic value far exceeds your imagination from looking mere 10 years into your forecast period. The following is a rare example, I know, but let’s say the year is 1975 and you just heard about this guy out in Omaha who used to run an investment partnership that crushed the market in its 12-year run, and that you now have the opportunity to invest with this young fellow through the publicly listed entity of Berkshire Hathaway for the next, probably, 20 to 30 or even 50 years. You sit down and read all his letters until you’re confident that Berkshire Hathaway is likely to turn out a wonderful investment. As the value investor that you are, you then start crunching the numbers to calculate Berkshire’s intrinsic value and for that, you use your usual required rate of return of 10% as your discount rate. Concluding your valuation, you’d probably estimate that given its extraordinarity and a 10-year high growth period, this business deserves a price-to-book of 5x or 6x and that the stock is trading at a significant discount so you add it to your portfolio. You’d make a great investment (obviously), but you’d be dead wrong in your valuation. Because the fact is that you could have bought the stock at 50x book value and still made your required 10% return (as of the end of fiscal 2020).

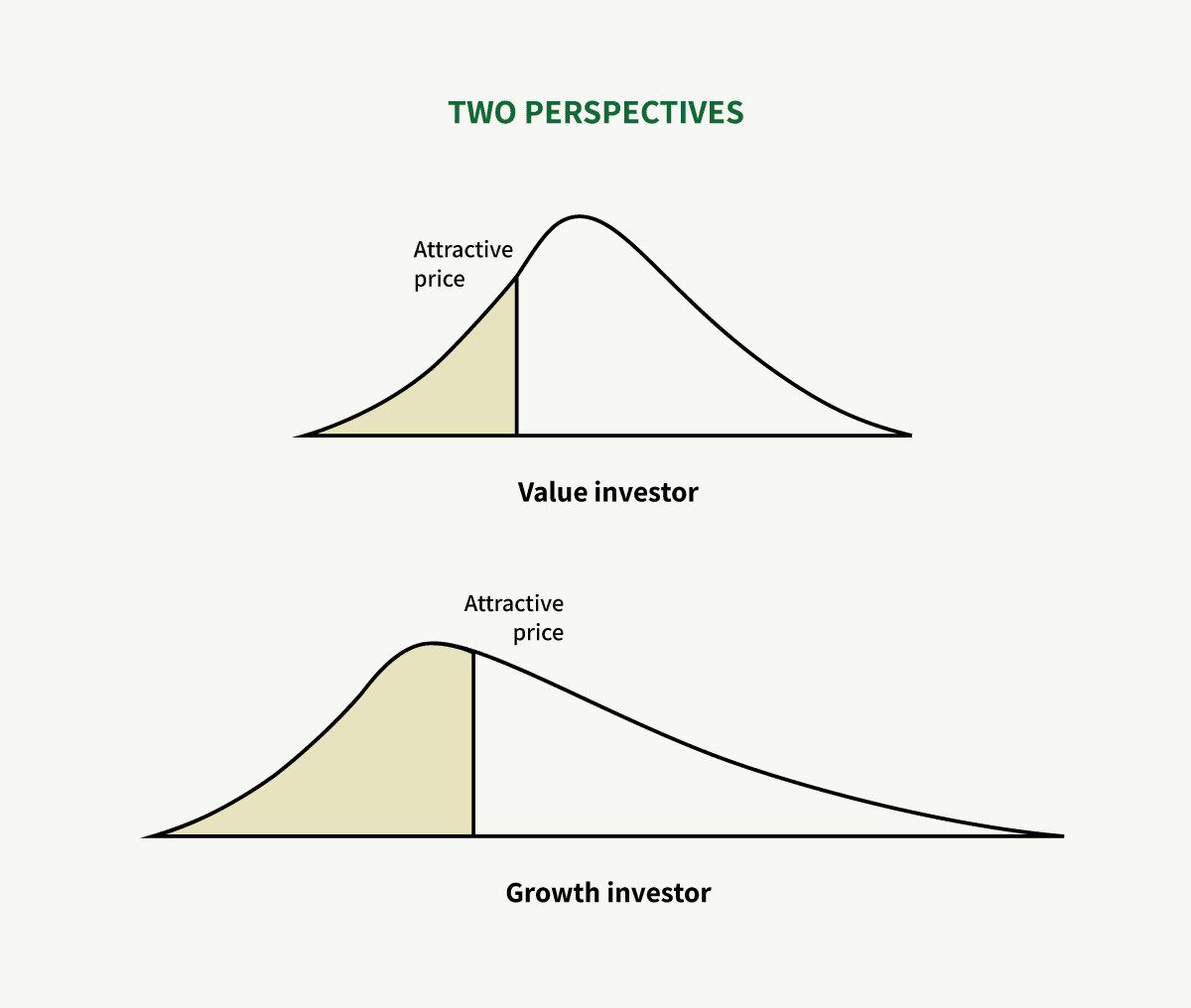

So I guess what I’m getting at is that you cannot really value an extraordinary business to a tee. Of course, you must acknowledge that Berkshire’s history could have turned out differently for various reasons and intrinsic value always exists on a probability spectrum. Therefore, I think the dividing bridge between what conventional finance defines as a “value investor” and a “growth investor”—which, by the way, is non-sensible—may be captured by this one idea: A rational value investor understands that cheap prices merely mitigate left tail risks and that the trick is to select the companies where the right tail may be longer than everyone anticipates.

A value investor works hard at cutting the left tail whereas a growth investor deems the right tail to be longer and is, therefore, more willing to take a stance longer on the right curve. Either way, they’re both trying to capture as much of the curve as possible along the spectrum of value.

All this naturally leads to the sit-on-your-ass philosophy discussion. Once you find a wonderful company and buy it at a fair-looking price, holding on means resisting temptations to sell. And that’s not a bit easy. In my experience, the most difficult job an investor faces is when to sell. And this predicament always shows up at the wrong time where politics, macroeconomics, corporate minutiae, etc. all come along to stress test and muddle your thinking.

One of the reasons why it’s so difficult to sit on your ass is that it sometimes feels irrational to do so. Charlie Munger has said, “Psychologically, I don’t mind holding a company I like and admire and trust and know will be stronger than now after many years. And if the valuation gets a little silly, I just ignore it. So, I own assets that I would never buy at their current prices but I am quite comfortable holding them… I cannot defend it in terms of logic. I don’t defend this logic. I just say this is the way I do it and it keeps me more comfortable to do it this way.”

There’s really no explainable rationality in holding on to a company that you would never buy at today’s price. But quality companies are just too hard to replace. If you study some of history’s best long-term investors, you’ll find that one of the most frequent mistakes made has been selling too soon. So when I sell a stock, neither valuation nor price targets play a significant role, but qualitative factors and investment opportunity costs do.

The last point I want to make in this discussion is that a strong quality filter is the most effective way to manage risk—and in my opinion, the only honest way—if you want to generate strong long-term returns by practicing the sit-on-your-ass philosophy. I’ve seen countless research reports in which the analyst tries to capture the risk of a company in the discount rate by conventional academic standards. Inherently, there’s nothing wrong with this approach. There are different ways of catching a mouse. When it’s fallible, though, is when you can tell the analyst has disregarded their understanding of business risk and replaced it with some proxy for volatility. Then the entire research turns into pumpkin. The best way to satisfactorily assess a margin of safety is by looking at what you qualitatively deem a safe bet: a wonderful company.

My continuous goal in the investing business is to build my investable universe, seek out a collection of wonderful companies, watch this collection over time, and pound when the time is right. In my current four-stock portfolio, I believe I have a sliver of such a collection bought at more than fair prices during times of stress. Of course, I wish I had more holdings and I do keep turning rocks, but I don’t quibble much with being this concentrated while waiting for opportunities to show up (which may start showing up soon).

Being very concentrated (and buying stuff on the way down) means differing largely from the mean, meaning there will be periods where the portfolio significantly underperforms the market and periods where it performs tremendously better. 2020 was an example of the latter, 2021 was an example of the former. The Junto portfolio got crushed by the index, underperforming the S&P 500 by an impressive 26.06 percentage points in 2021. I take short-term pains with equanimity in the pursuit of performing satisfactorily in the long term.

To resist making this letter longer than it already is, I’ll not provide commentary on individual positions this time around. This is partly because I don’t have anything informative to say other than what’s already been said in my last member emails and write-ups. I think Fairfax‘s recent opportunistic buyback is a testament to its attractiveness and is only the beginning of what’s to come and I continue to think that Alibaba is a generational opportunity. I continue to believe that this small collection of companies is ripe to perform excellently over the long term while I keep looking for other ticks on the punch card to use at the right prices. Thanks for reading and for all your support.