Yesterday, I added a Canadian stock to the investment portfolio.

This stock is the insurance holding company run by Prem Watsa, Fairfax Financial.

And there’s a great reason why we bought a sizable chunk of it. But first, let’s talk a bit about Prem Watsa himself.

***

“The Richest, Savviest Guy You’ve Never Heard Of”

Born in Hyderabad, India, in 1950 and the son of a school teacher, Watsa is a first-generation entrepreneur coming from poor conditions. After gaining a chemical engineering degree at IIT Madras in India, he decided that he wanted to move to Canada in the early 1970s with just $8 in his pocket.

After settling in Ontario with his elder brother, he thereafter wanted to pursue an MBA at the University of Western Ontario Business School. And to fund his tenure, he worked as a door-to-door salesman selling air conditioners and furnaces.

After graduating, Watsa began his professional career in 1974 working for the investment department at now-defunct Confederation Life Insurance Co in Toronto. As the only one of the four called-in candidates to show up for the job interview, Watsa got the job as a research analyst. He soon after got a promotion to equity portfolio manager for pension clients. At the job, Watsa’s manager, John Watson, was the first major influence on his professional career and taught him all that he knew about investing based on Benjamin Graham’s value investing principles. Graham’s principles of investing based on buying a dollar’s worth for less than a dollar with a sufficient margin of safety stuck with Watsa throughout his career as he learned to reject theories of quick returns in order to focus on long-term investments.

In 1984, he broke loose to start his own venture by the name of Hamblin Watsa Investment Partners with a couple of partners. And a year later, he took control of a small, distressed Canadian trucking insurance company named Markel Financial. This became the start of an incredible story.

After reorganizing the company, Watsa changed the name from Markel Financial to Fairfax Financial which from then on served as an insurance holding company and Watsa’s investment vehicle (with Hamblin Watsa running the investment arm). Why the name Fairfax, you ask? The name was short for fair, friendly acquisitions.

Since then, the unorthodox and iconoclast Watsa has become a legend in the Canadian insurance and investing business. By running an efficient insurance operation and prudently investing the float coming out of it, Fairfax has managed to grow the book value from $1.52 per share to $486.10 from 1985 to the end of 2019. This is a compound annual return of 18.5%. That’s even after starting to pay a dividend in 2001 and a somewhat lackluster performance over the last few years. Over the period, assets grew from $30.4 million in 1985 to $70.5 billion in 2019 and insurance float grew from $21.6 million to $20.2 billion.

Despite success right off the bat, Fairfax for years managed to stay below the radar with Watsa barely speaking to any reporter until finally beginning to hold investor conference calls in 2001. And then he started to get a tonne of attention when in the 2008 meltdown Fairfax significantly outperformed the market while afterward picking up shares at discounted prices. That’s when the Toronto Star in a 2009 profile called him the “richest, savviest guy you’ve never heard of”.

Now, why am I telling you this story first? Because a lot of people have begun questioning the investing prowess of Watsa and Fairfax over the last couple of years. So much that the shares we picked up yesterday were priced at 60% of book value.

But we’ll get to that later.

First, a Little About Fairfax and Insurance

Fairfax is an insurance holding company engaged in property and casualty insurance, and reinsurance, and investment management.

Let’s begin with insurance of which Fairfax has operations across the world.

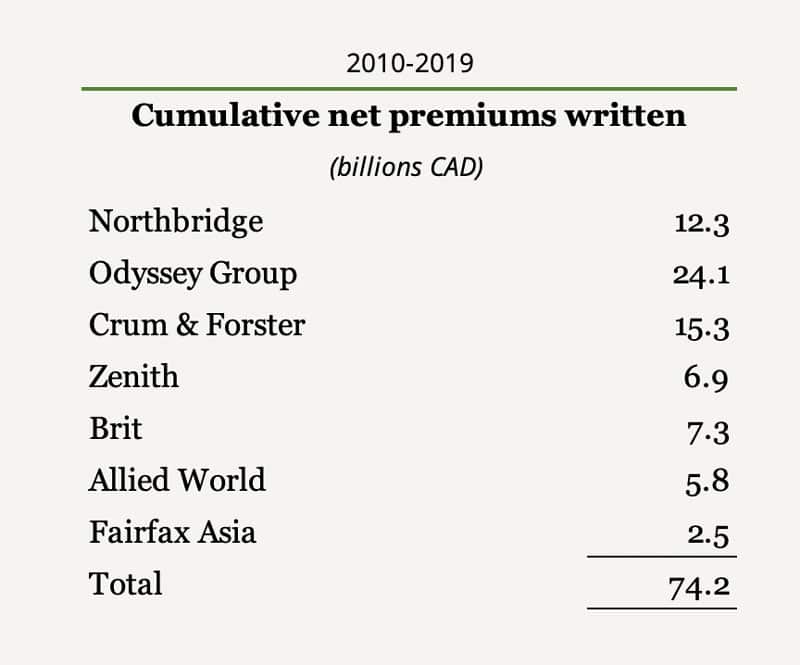

Here are its major subsidiaries in terms of cumulative net premiums written from 2010 to 2019:

A lot of the international operations included here (i.e. Brit, Allied World, and a lot of other subsidiaries and associates) have been established over the past five years as Fairfax has expanded opportunistically into the UK, Eastern Europe, Latin America, South Africa, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Ukraine, Vietnam, Greece, and India.

All Fairfax’s insurance businesses are managed decentralized with each CEO responsible for running their own companies.

Before we continue, let’s quickly discuss how to determine the attractiveness of an insurance business such as Fairfax which is largely engaged in property and casualty insurance.

Two factors matter: underwriting profitability and investment returns.

Firstly, underwriting profit is the term pretty much everyone is familiar with. It is the difference between the premiums sold and claims paid out. They are the money that insurees pay every year for an insurance policy, and the money paid back to them when there is an accident, burglary, or other circumstances. If premiums exceed the total of expenses and eventual losses, the insurance company registers an underwriting profit.

The measures used to gauge whether insurance companies operate their underwriting activities profitably are the loss ratio, the expense ratio, and the combined ratio.

Many make the mistake of focusing solely on losses when looking at insurance companies. Headlines will tout the impact of a major hurricane, blizzard, or other catastrophic events on an insurer’s profits, making it seem as though that’s the only determinant of profitability on a long-term basis. As a result, the loss ratio, which focuses solely on what an insurer pays out in claims, often becomes the primary focal point for those looking at an insurance company’s stock.

However, just as important to profits is how well an insurer manages to run its operations, and that gauge shows up in the insurer’s expense ratio. The expense ratio takes operating expenses and divides them by earned premiums.

And then, the combined ratio essentially takes the loss ratio and the expense ratio and combines them. A combined ratio of less than 100 shows that the insurance company is pulling in more money from premiums than it’s paying on claims and overhead, indicating a profitable enterprise.

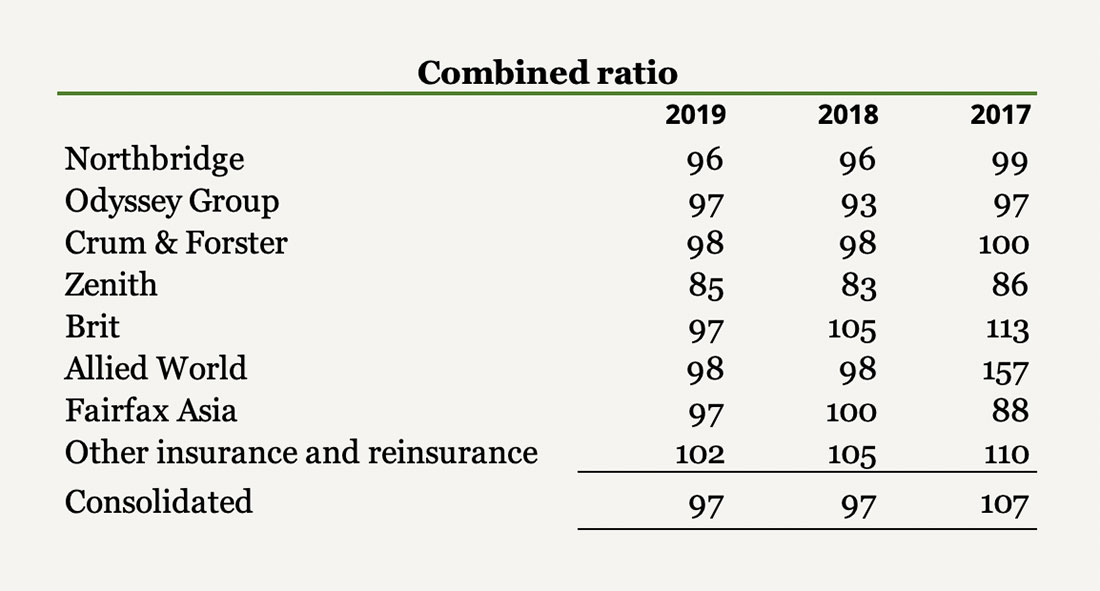

The following shows the combined ratios of Fairfax’s insurance subsidiaries for the last 3 years.

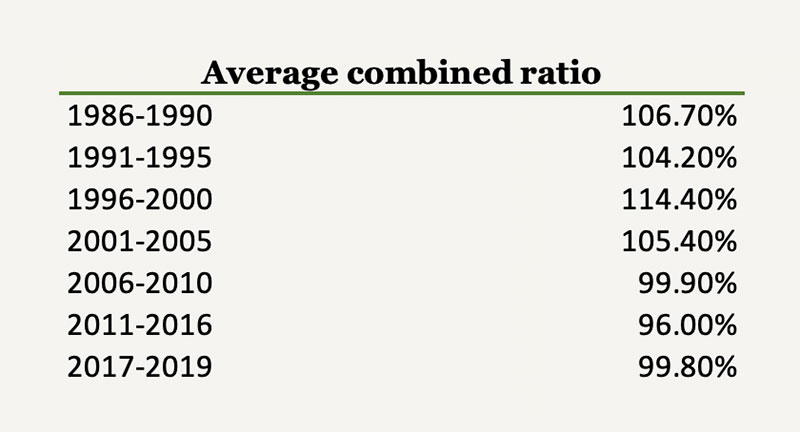

As seen, it’s been a good couple of years. And if we zoom out to 34 years of operation, the underwriting profitability has trended well into profitable territory.

Over the last 14 years, Fairfax’s insurance business has had a combined ratio of less than 100.

Now, can we expect this to continue? Well, considering the company’s impressive history of increasing efficiency and its recent aggressive expansion in global growth markets, I believe it very likely that Fairfax will continue to underwrite profitably in most, though certainly not all, future years.

The reason why is that it’s normal for property and casualty insurers to undergo an underwriting cycle which typically lasts for about 3 to 5 years. During this cycle, prices (premiums) on policies can experience intense competition as competitors reduce prices to retain a certain level of business and capture market share. Frequently, prices of securities in the insurance company’s portfolio fall below sustainable levels and lead to losses as claims on policies are paid out. The insurance company must then liquidate portfolio assets to supplement cash flow, and share prices may drop. Insurers are forced to raise the prices of policies and underwriting profitability can flourish once again, opening the door for renewed competition.

And therefore, the insurance business’s underwriting profitability is not all that matters. For insurers that are also savvy investors, it actually matters little. In fact, the industry’s overall return on tangible equity has, for many decades, fallen far short of that achieved by the S&P 500.

Then why are we even interested?

Introducing float.

The easy way to understand float is to use the term, “other people’s money”. It’s the money that the insurance company has collected in premiums but not yet paid out in claims. It is very similar to how a bank will collect deposits, invest that money (through loans), and then will repay that money in the future with a withdrawal.

Meanwhile, insurance companies get to invest that float. And if the company is investing the float well, it can lead to outstanding economics. If the float is coupled with a profitable underwriting business, the insurer is even being paid to invest it.

And, other than gaining a higher return on capital than insurance peers, the insurance company can also choose to speed up or slow down the number of policies written during overheated or undervalued market conditions. This is a significant advantage compared to peers who are often forced to invest in fixed income securities to match policy durations.

As the business and amount of written insurance policies grow, so does the float.

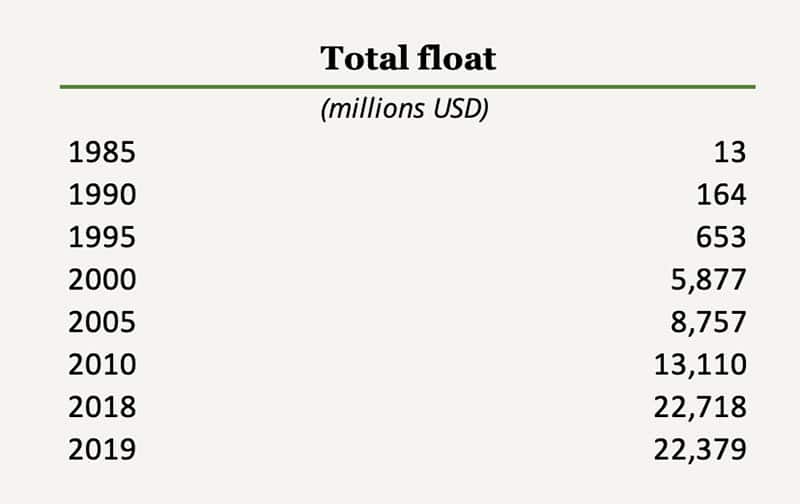

Here’s how Fairfax has grown its float since 1985:

And, here are the average total returns that the team at Hamblin Watsa has generated on the investment side of the float brought in:

The combination of increasingly profitable underwriting operations and high returns on investments is what has allowed Fairfax to grow its book value by an astounding 18.5% per year.

But as you have probably noticed, even though the insurance side has done well, Fairfax has underperformed the overall market on the investing side for some years now.

Investment Performance

As we like at Junto, Prem Watsa is an avid practitioner of value investing. And, of course, that has served Fairfax extremely well over the decades. However, some are starting to doubt whether Fairfax can perform up to these standards in the future.

Lackluster investments over the last years include that of its largest investment, BlackBerry, a stock that has been in deep-value territory for years now. Despite CEO John Chen’s best efforts, the market has yet to see an opportunity in the business. Fairfax’s problem with such an investment in what turned out to be an 11-year bull market left a lot of opportunity costs. Other underwhelming investments include that of Reitmans and Torstar.

Meanwhile, back in 2014, Watsa started making a huge bet on deflation hitting the developed world in a big way. Fairfax ended up paying $650 million for several derivative contracts that would pay massive premiums if the United States, Britain, France, or the European Union saw significant deflation by 2022. The total payout was capped at US$109 billion, but the likely payout was only $10 to $20 billion. The bet has yet to work out and has 2.8 years to go.

To be fair, successful decisions include his big bet on India. Since starting Fairfax India in December 2014, the company has made 10 investments in the country of which the crown jewel is the company’s 54% ownership of Bangalore International Airport – a marvelously managed airport and the fastest growing in the world. Fairfax India has done very well indeed.

Yes, the investment side of Fairfax has been disappointing for some years now considering the company’s history. But I think that dwelling on individual investments tells us that the market cares more about the short-term stuff than the long-term perspective.

It’s funny. It reminds me of the story I read in the book by Spencer Jakab called Heads I Win, Tails I Win. It’s about the Fidelity Magellan Fund run by legendary investor, Peter Lynch, from 1977 to 1990 which was one of the most successful mutual funds in history. In it, Jakab writes:

During his tenure Lynch trounced the market overall and beat it in most years, racking up a 29 percent annualized return. But Lynch himself pointed out a fly in the ointment. He calculated that the average investor in his fund made only around 7 percent during the same period. When he would have a setback, for example, the money would flow out of the fund through redemptions. Then when he got back on track it would flow back in, having missed the recovery.

In the market, the short-term sentiment dominates—to the investor’s detriment. It pretty much always will.

How the Market Prices Fairfax – and How We Took Advantage of It

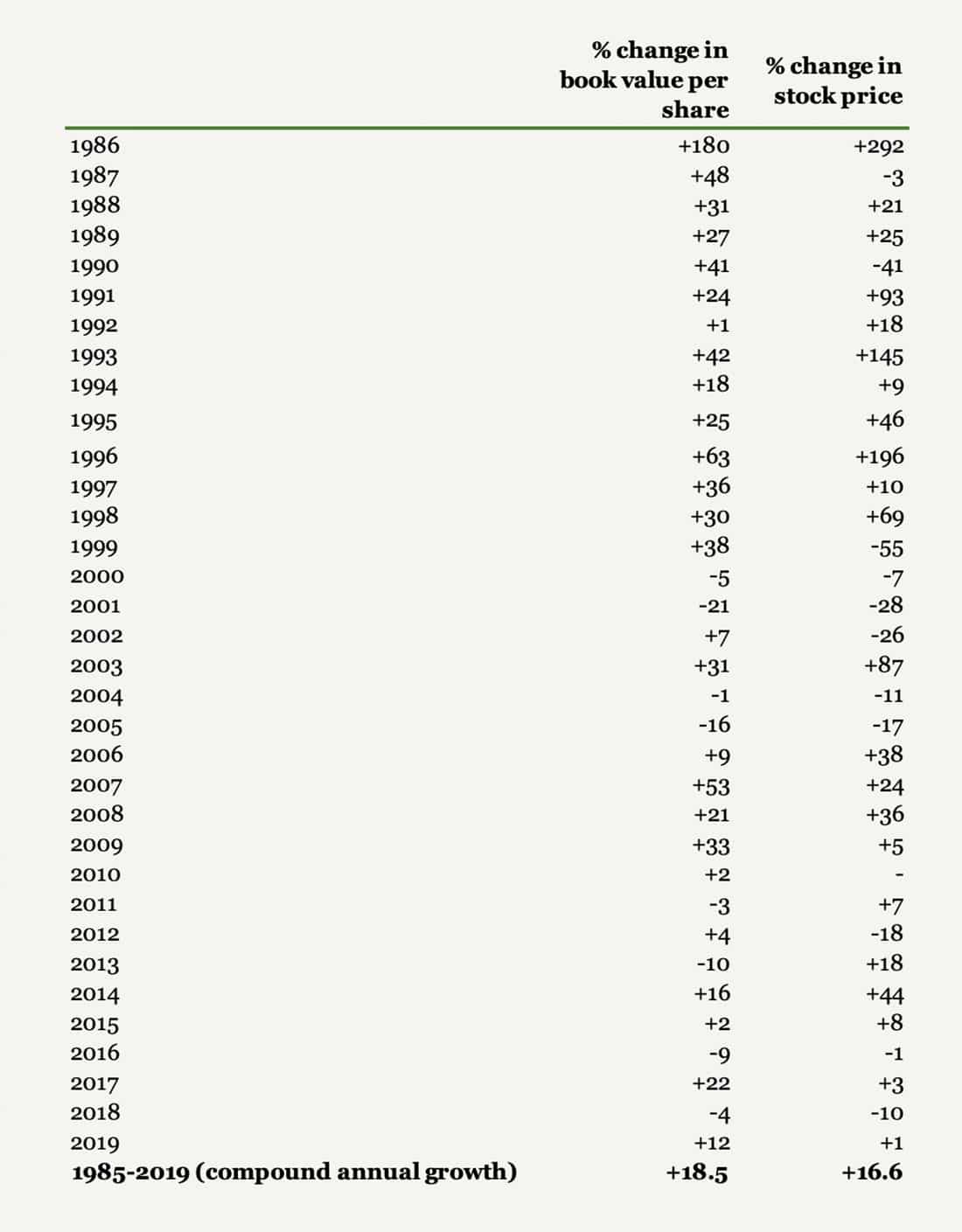

But what the market often forget, is that the long-term investing game is a very lumpy game. The same goes for soft insurance underwriting markets. Fairfax is no exception in this regard. Consider the 34-year history of how book value and the share price have developed from year to year:

The interesting thing about how the current market affects the stock of Fairfax is that we yesterday were able to pick up our holding at a price of 60% of the company’s book value. Only a few times in the company’s history has that been possible, and despite short-term pessimism, long-term investors have been healthily rewarded over the coming decade, especially if they added to their positions along the way.

In each of these years of 2002, 2006, and 2009, the share price struggled despite improving fundamentals. Often, the fall in price came after a year or two of book value declines. If investors purchased at or below book value during these periods, they would have been healthily rewarded for patience and long-term outlook.

Meanwhile, Watsa targets a 15% long-term annual return on shareholder’s equity which should be achievable as long as the company earns “7% on [the] investment portfolio and [the] insurance operations produce a combined ratio of 95%.”

If Fairfax can generate even 5% annual returns on its investments, book value should rise by about 10% annually. In fact, that’s pretty close to the real returns of Fairfax over the last two decades. Buying at 60% of book value would equal close to 17% return on investment. And that’s excluding the currently more than 3% dividend yield paid with only a 16% 2019 payout ratio.

Of course, despite the company’s downturn-resistant insurance operation, we are living in a very uncertain economy right now, and the book value of Fairfax may well take a hit for the coming year, which would bring the price-to-book closer to 1. Nonetheless, I find our purchase price incredibly attractive. And I believe the company’s intrinsic value far exceeds the current book value.

In short, I am very confident in the ability of Watsa and the team at Fairfax to continue compounding at very satisfactory rates of return over many years. And I expect Fairfax to deliver these returns with a sizable margin of safety.

The reason for my confidence is pretty simple. It’s a function of a bunch of lollapalooza effects in how Fairfax is governed.

Fairfax’s Ethos

“If you have the philosophy but don’t have the structure, it makes it very difficult to implement a value-oriented philosophy.”

– Prem Watsa

Fairfax has been under the present management since it was created in September 1985. And over its 34-year history, the company has always operated with a small team which, with great integrity, team spirit, and no egos, has protected the company from unexpected downside risks and which has taken advantage of opportunities when they arise.

Meanwhile, by its way of long-term orientation and decentralized governance of every portfolio company, Fairfax has right from the beginning operated on a foundation of the right amount of trust, openness, incentives, and integrity.

Like Berkshire Hathaway, Fairfax’s system operates on a seamless web of trust.

Put simply, there’s money in keeping things simple, having common sense, and being trusted. That’s the ethos we like at Junto.

Ending Remarks

At Junto, our approach is to make concentrated investments in undervalued stocks of high-quality companies that we would prefer to hold forever. Through that approach, we aim to compound our invested capital at rates of return that beat the S&P 500 and MSCI World Index net of taxes over the long run.

But perhaps more importantly, we look to invest in businesses that have the same objectives and values as our own through honesty, integrity, and calculated risk-taking by exceptional management with a decade-long orientation. When we find that at an attractive price, we bet on it.