When I first set out to dive into Momo Inc. I felt I had a good grip on understanding the business and where it was heading.

But after spending an hour or two reading through the annual report, I found that was not necessarily the case. Momo’s offerings are rather simple to understand, but how they monetize them—and how this will change in the future—is a bit more tricky.

Therefore, there is a certain degree of uncertainty involved with Momo’s future prospects. And as I will argue in this write-up, that is highly reflected in the company’s current market price. So much so that I would argue the current price reflects a significant margin of safety despite the uncertainties surrounding the business.

To be clear before diving in, Momo is once again a Chinese technology business. Compared to Western parallels, Chinese technology businesses have always been priced more gently, especially now being afflicted by negative market sentiment from the PRC meddling with tech companies and the talks of ADR delistings as a result of the ongoing U.S.-China trade war. That is indeed the case of Momo, and after spending a decent time on the company on and off over the past month, I made the conclusion that it is too cheap—one of the rare ones to find in this market environment. I also think I know why it is too cheap.

Momo Inc. Is a Two-Bet Social Connectivity Company

Momo owns a small collection of apps within social discovery and entertainment. Its first and biggest application, the core Momo app, allows people to connect and interact based on location, interests, and a variety of online recreational activities.

By recreational activities I mean all kinds of them. The things users can do through the Momo app today are a result of continuous additions added to the platform throughout the years. These include live streaming, short videos, dinner party games, and even virtual karaokes. While it was originally thought of as a single-function application (finding strangers to get to know nearby), the team at Momo has created a transformed version of how people interact and “play” with each other on a social medium.

Live streaming was overwhelmingly the secondary function of Momo that took up the most popularity. Revenues really took off after this launch making it the cash cow of Momo’s business. We’ll get back to how it did so in a minute.

Momo also owns the Chinese dating app Tantan which they acquired in May 2018. Founded in 2014, Tantan is basically the Chinese Tinder and the leading dating app in the country. It’s the star of Momo’s product portfolio.

Like Tantan, Momo itself is a fairly young company. The company was founded in 2011 by Yan Tang, Zhang Sichuan, Lei Xiaoliang, Yong Li, and Li Zhiwei. Yan Tang was the chief executive officer since inception and has been the Chairman of the board since 2014. Prior to founding Momo, he was editor-in-chief at NetEase. He resigned as CEO in November last year to which he left the position to Wang Li who has also been with Momo from the beginning.

As his departing words as CEO, Yan Tang said the following of Momo’s mission in the Q3 2020 earnings call:

Nine years ago, I started Momo with an idea to help people discover new relationships, expand their social connections and build meaningful interactions. This is a basic human demand that everybody needs regardless of geolocation and cultural background. But this is also something that we, Chinese people, particularly need because of the uniqueness we have here in China from an economic, societal, and cultural perspective.

Let’s dive a little more into how this idea has been carried out through the offerings of Momo and Tantan.

Core Momo Is Saturated With Users but Still Finding Its Way

While Momo is mostly known for being a live streaming app, management claims that it’s really a social app.

The core Momo app is a social media powered by geolocation that allows users to connect with other users nearby. Like other social media platforms, the app works using user-profiles and a main feed. But unlike a traditional feed, Momo works by mixing media posts from other nearby users, curated by Momo’s proprietary algorithms to match users based on the highest likelihood of successful interactions.

Then why is it that Momo is highly reputed for being a live streaming bet mainly in the investing community? The reason is that the secondary live streaming function practically makes up all its revenues.

Momo added live streaming as a secondary feature to the app in 2015. Initially, the function was limited to official shows hosted by Momo under the name of Momo Live. As things worked out well and live streaming became a terrific bet, the company opened up the service in April 2016 to all users on the platform so that anyone could apply to become a live broadcaster.

It wasn’t just Momo that seized this trend. In 2016, the Chinese live streaming industry exploded and there were at one point over 200 apps offering live streaming. The market consolidated when the smaller players had trouble keeping up with the growth and user retention. Momo was one of the players that continued to thrive by taking advantage of its social features that made users come back day in and day out.

A big part of that was the fact that Momo introduced the live streaming function by exclusively hosting official shows with professional musicians. It was a smart move. The company offered these live shows for free and users would have the option of purchasing in-show virtual items in the form of filters and lenses (which is practically a user donation to the broadcaster) and interact with the broadcaster directly (requesting songs and the like). Momo monetized the service by taking a percentage of these virtual items purchases with the remaining going to the broadcaster and talent agencies.

The company then doubled down on attracting up-and-coming broadcasters when it went into TV production and created PhantaCity, a live audience TV show which first aired on the app in 2018. It quickly became the most talked-about variety TV show on the internet.

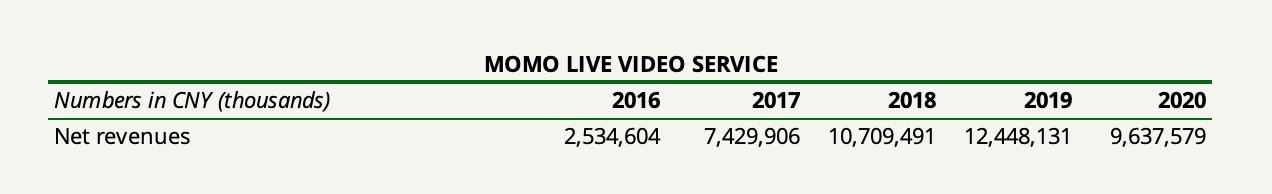

When I first read about this business, I thought that there’s no way in hell it would amount to billions. But I was in for a surprise. As it turns out, this is big business. Over the next three years after the live streaming launch in 2015, those revenues compounded at 62% annualized to quickly become Momo’s largest segment.

But clearly shown above, these live streaming revenues went into a slump in the year 2020—a year in which one would expect live streaming to pick up drastically along with other social technologies as the world shut down from the Covid-19 pandemic. There are certainly reasons to be wary of how this played out which we’ll get back to later.

Now, a thing I find more interesting is how users pay for the virtual items within live streaming.

Virtual items must be purchased using Momo’s virtual currency (Momo coins). The coin price is linked to a real-world currency and purchased through the App Store, Google Play, or other payment channels. The payment platform takes a rate of the amount (in Apple’s case 30%) after which Momo books the proceeds as deferred revenue. When the user spends the virtual currency, the amount moves to the income statement and the revenue sharing amount is charged to cost of revenues.

These virtual coins are non-refundable with no expiration date and they must be spent on virtual items.

At the end of the fiscal year 2020, Momo’s deferred revenue (which also includes membership subscriptions that we’ll get back to in a minute) totaled about CNY512 million. To Momo, this is virtually free debt with a cost of 0% (not negative since the impact of breakage is insignificant). Out of the total liabilities, deferred revenue amounts to ~6.1% which is quite the amount.

This operation is indeed assisting in lowering the company’s overall cost of debt. Other than lease liabilities of CNY269 million, the company has outstanding convertible debt of CNY4,659 million expiring in 2025 (with little dilution risk at a conversion price of approximately $61.37 per ADR). These notes carry an effective interest rate as low as 1.61%.

What I just described is what Momo segments as its live video service. As wonderful as this business may sound so far, I’m going to spoil the fun early by breaking the fact that it’s likely going to be much tougher for the company to keep up with this business in the future.

But live streaming luckily isn’t Momo’s only revenue stream. After all, management claims that over 80% of the time spent on Momo is in a variety of social experiences that are not related to live streaming at all.

The other segment consists of value-added service (VAS) which is directly attributable to Momo being a social connectivity app. Value-added service consists of membership subscriptions and a virtual gift economy (not to be confused with the virtual items business).

The core Momo app offers a VIP membership which costs CNY12 monthly. A VIP membership opens up for additional functionality that enhances the social experience through privileges such as VIP logos, higher limits on the number of users that the member can follow, access to specific emoticons, the ability to see a list of recent visitors to their profile page, and so on.

Like virtual coins purchased by users, Momo collects membership subscriptions in advance and records them as deferred revenue. Revenue is then recognized ratably over the contract period as the membership subscription services are delivered. Together with live streaming, this has allowed Momo to grow with negative operating working capital since its founding.

The other part of value-added services, the virtual gift economy launched in Q4 of 2016, is basically the same thing as virtual items within live streaming. However, instead of sending virtual donations to live streamers, virtual gifting within value-added service is, according to management, deeply connected with other non-live streaming social activities.

Momo shares a portion of the revenues with the gift recipients.

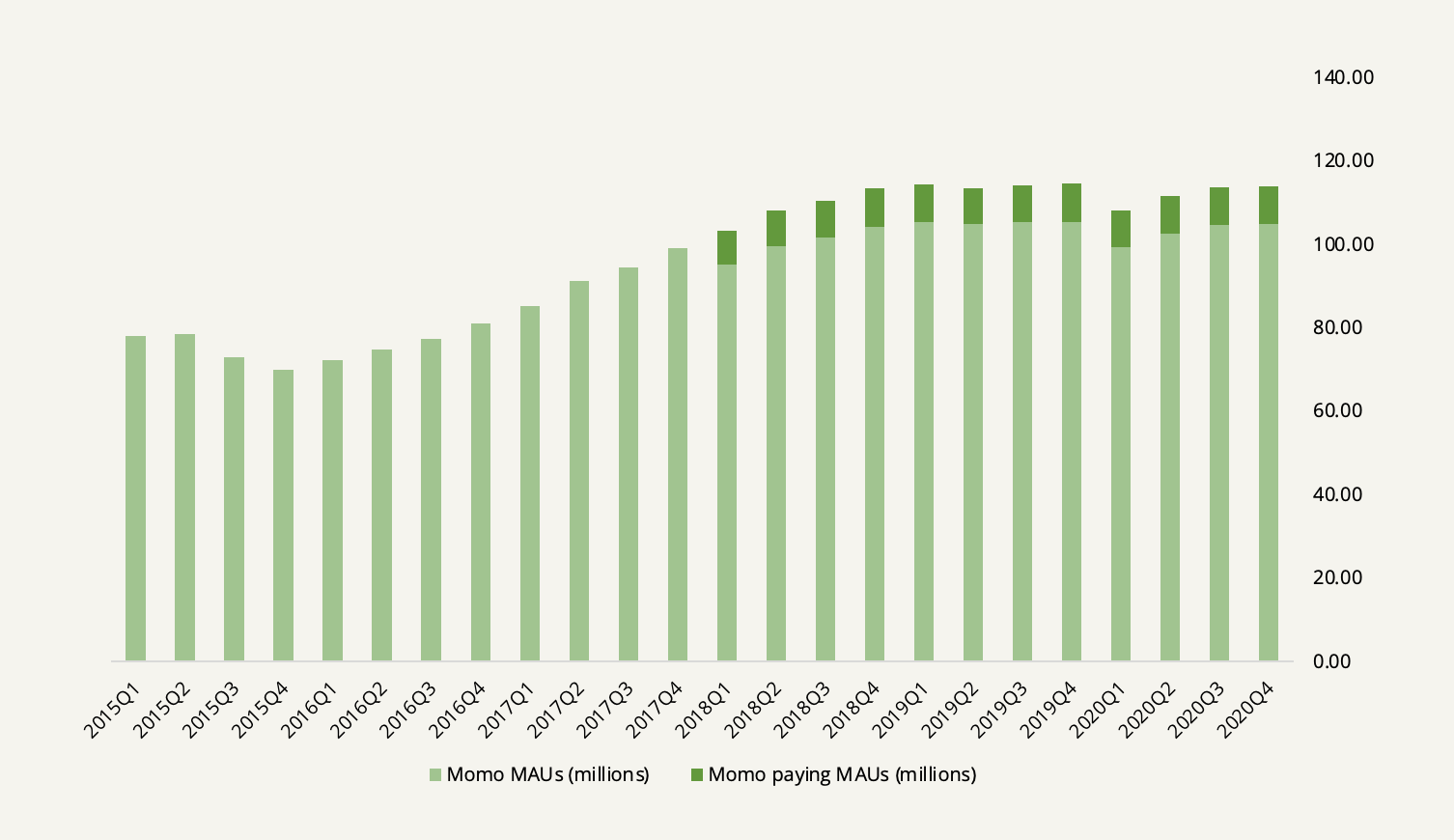

By the end of 2020, the core Momo app had 113.8 million monthly average users (MAUs) which have grown considerably over the years but look to stall at the current level.

Before sizing up the value-added service segment, we’ll move on to Tantan which is also placed within the segment.

Tantan Is Now China’s Leading Dating App

Prior to the emergence of Tantan, Momo was the main app used in China when people wanted to find romantic relationships because it pretty much was the only app that connected people within a certain proximity.

When Tantan came along in 2014, that changed the picture. Because over the next few years, Tantan was quick to become the leading dating app in China for the younger generation, essentially scooping up the market as the only pure-play dating platform in the country.

It was therefore an intelligent move when Momo went ahead and acquired the company in 2018 for $613.2 million in cash and 5.3 million newly issued Class A shares (a total deal value of $735 million). At the closure of the deal, Jeremy Choy, head of M&A at China Renaissance, the sole bank involved, said:

In one deal we’re creating the only player left in China’s dating app market.

Tantan is in a lot of ways the Tinder of China. It uses the same swipe and match system. And like on Tinder, users are allowed to add up to six pictures to their profile.

Like with the core Momo app, Tantan commenced monetization in 2018 by offering membership subscriptions along with some other premium features on a pay-per-use basis. By subscribing to the Tantan VIP membership—which like the core Momo app is priced at CNY12 per month—users can enjoy unlimited numbers of swipes, use “Super Likes”, get a special badge, and use location roaming. In November 2019, Tantan launched a “Quick Chat” feature that allowed users to get instantly matched with each other based on age and location where they can strike a conversation with their photos blurred and complete profile locked. The fully exposed photos and complete profiles will first be available after the users exchange 20 messages. A Tantan user can pay to unlock the photos in advance.

At the end of last year, Tantan introduced a higher tier to its membership solution by the name of SVIP (Super VIP) which is currently priced at CNY30 per month. The new membership model bundled existing features such as “See Who Liked Me,” “Quick Chat”, and a complete set of VIP privileges, as well as a number of new premium features such as “advanced filters” and “recover the unmatched”.

Being early in its monetization, Tantan is currently unprofitable and made a net loss of CNY454 million in the fiscal year 2020 on revenues of CNY2,368 million. And although it’s moving fast towards profitability, management has emphasized during the last couple of conference calls that revenue is not of its short-term priorities and neither is profit. They believe that profitability should be the outcome of user growth to which I agree. In order to entrench its position as the leading dating platform in China in a big way, Tantan will need to continue to attract and retain users which will continue to involve considerable expenditures for the next couple of years.

It’s all going quite well. Although Tantan has been vague in disclosing user numbers over the years, the latest user numbers showed that Tantan currently has 10.5 million daily active users and 35 million monthly active users. Out of those, 3.8 million are paying users. In comparison, Tinder was last estimated to have about 60 million monthly active users with about 7 million of them being paying users.

These numbers are growing fast, and with a secular tailwind in China’s dating market of 200 to 300 million single adult population, the potential is vast. According to management, the potential for Tantan within value-added service is likely to bigger than the core Momo app which itself is growing fast. My take is that Tantan should be able to at least double its user base where it can potentially be much bigger when taking overseas markets into account. Consequently, I’m certain that value-added service is Momo’s future and Tantan plays a huge part in that.

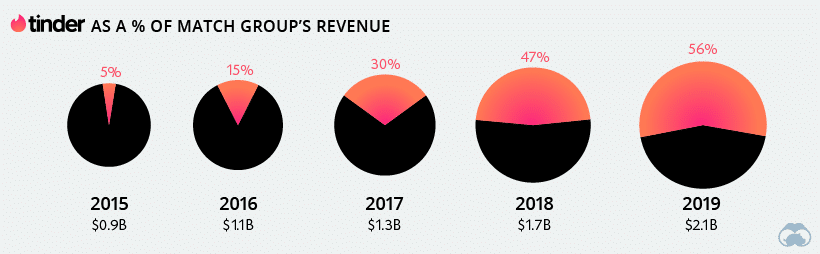

To get another feel for Tantan’s potential, the following shows the development of Tinder’s revenue contribution to Match.com.

Let’s turn our attention back to Momo’s biggest segment in live video service and the problems surrounding it.

Live Streaming Might Hit a Wall in the Near Term

Momo’s still lucrative live stream business is facing stagnation and even began to contract considerably in 2020. More specifically, live video service revenues declined 22% for the full fiscal year compared to 2019 with the fourth quarter showing a considerable decline of 31%.

There are a couple of reasons to link to this decline which were mostly evident in the second half of 2020.

First, Momo made a series of product adjustments beginning in August that allegedly were supposed to enhance the long-term health of the live stream business by making adjustments to certain interactive features. Management called this a “structural reform” to revive its long-tail content ecosystem. These changes apparently had quite the negative impact on live stream revenues.

At the Q4 2020 earnings call, Wang Li said:

Although the initial product adjustment in August caused a significant negative impact on revenues, it was a critical step in eradicating the undesirable practices that were harmful to the long-term health of the business.

I get why the content ecosystem would be a concern to address. Momo’s live stream business has historically been heavily powered by a small number of huge broadcasters and users which has little to do with the core purpose of the social app. As Momo works hard on creating a long tail content ecosystem catering to smaller user cohorts, it can better promote content that cultivates the social attributes of the core Momo platform. Whether it will succeed in doing so will be another matter.

The second reason for the live stream contraction lies with the company’s ad spent. Ad spending basically halted during the second half of 2020 as customer acquisition costs increased considerably when Chinese education and gaming companies became aggressive in seizing the post-COVID market surge and flooded Momo’s marketing channel. Since Momo’s marketing strategy is heavily focused on ROI, the company decided to stay on the sidelines for a long period.

But the most pressing reason I think management leaves out as a core explanation for the contraction is that the live streaming industry is increasingly becoming a cutthroat competition. Momo is up against some heavy competitors and industry consolidation does not make it any easier.

Momo’s biggest competitors within live streaming include ByteDance’s Douyin (known as TikTok in the West), Weibo’s Yizhibo, and YY Live which was recently acquired by Baidu in an all-cash deal worth $3.6 billion. These huge live stream products all possess competitive edges which Momo does not. For example, Yizhibo has a high presence of key opinion leaders (KOLs) originating from the main platform of Weibo which arguably competes with Momo’s whale broadcasters.

To counter, Momo implemented a new incentive program at the end of 2020 in order to secure key broadcasters—the ultimate source of its current live stream cash cow. This incentive plan secured the highest-grossing performers with exclusive multi-year contracts while enticing new performers and talent agencies. To ensure the stableness of its content supply, Momo has signed these “Golden” contracts with broadcasters accounting for 70% of Momo’s live stream revenues. Consolingly, this new incentive program has had little to no effect at the gross margin level with only Q4 2020 showing the effect so far.

I find it difficult to predict how Momo’s live video service will turn out. Management seems confident that it will continue as the company’s cash cow. In valuing the company later, we will have to be conservative in our estimates here.

Nevertheless, what the live stream segment lacks in growth is partially made up for in the rapidly growing value-added segment.

Value-Added Potential: Integrating Momo and Tantan

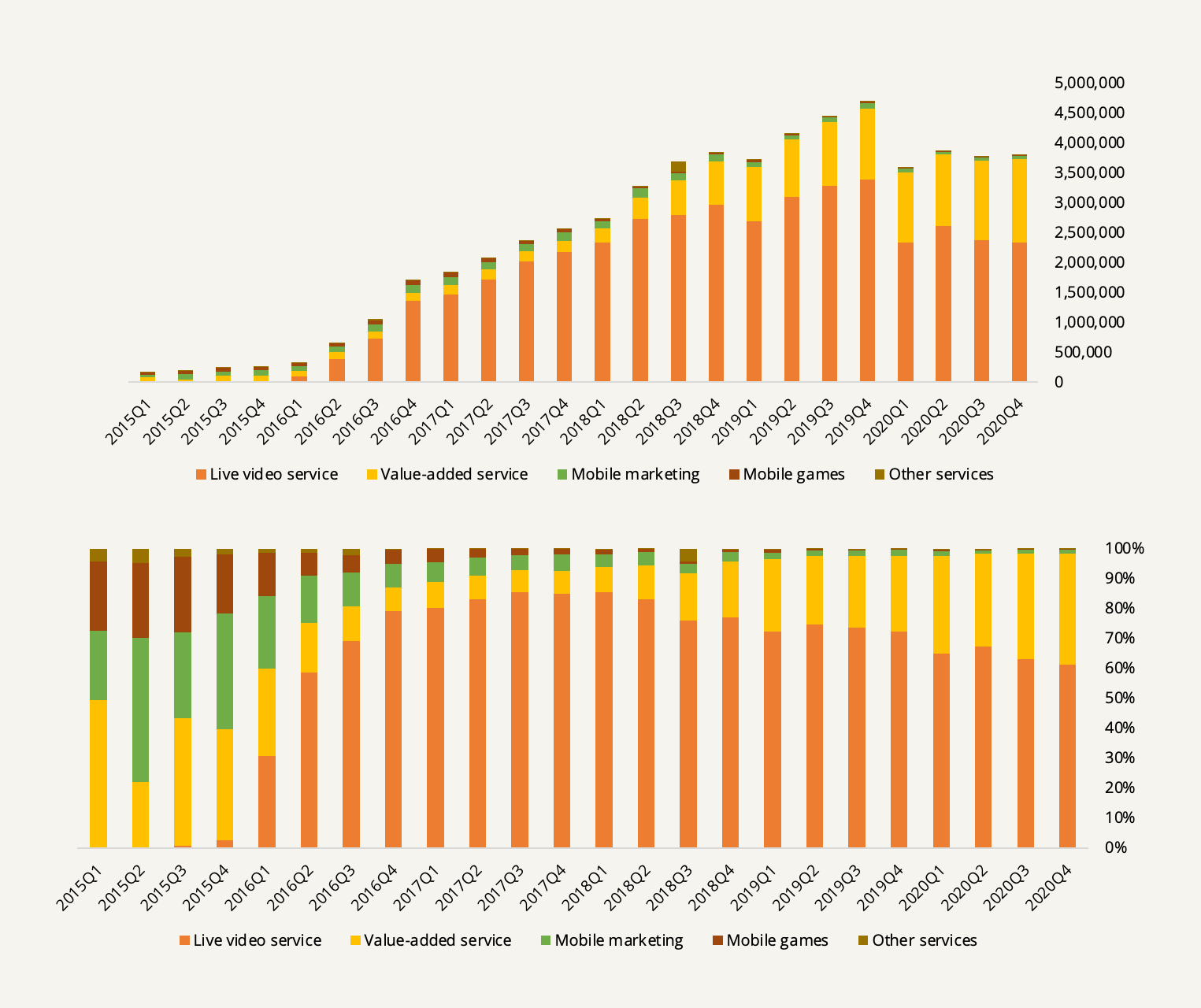

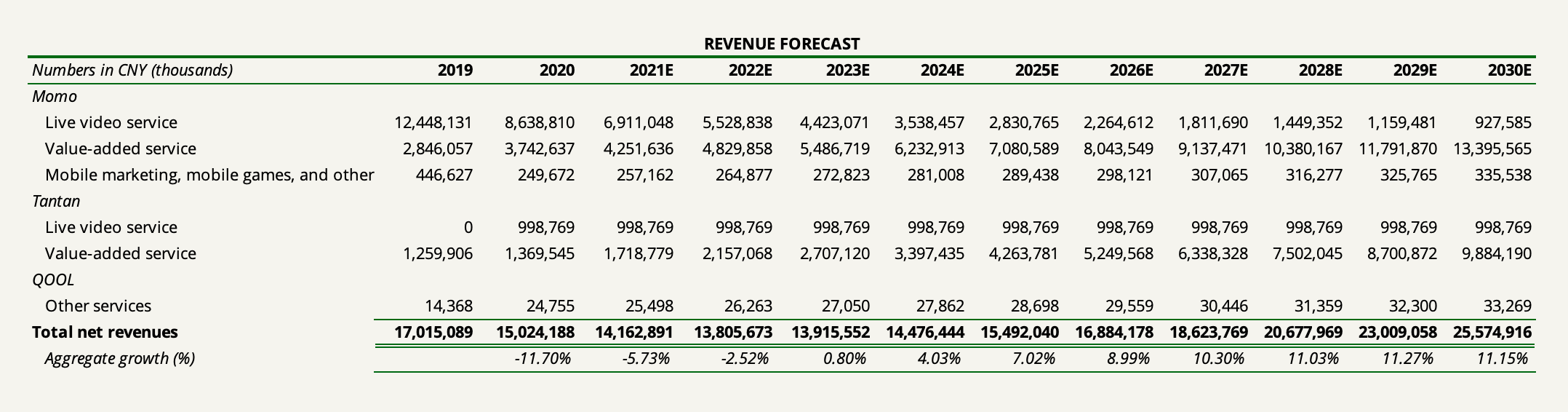

The following shows a total revenue breakdown of Momo’s operations including the smaller but insignificant segments of mobile marketing, mobile games, and other services.

For the past five years, Momo’s value-added service segment has grown at a cumulative growth rate of 62.6%. This is clearly the area in which management sees the biggest potential to drive Momo forward in many years to come. And rightly so.

Management has shown commitment to drive a higher level of collaboration between Momo and Tantan. So far, Momo has arguably ridden on Tantan’s flywheel growth trajectory as the country’s leading dating app with the highest network effects and the fact that the core Momo app and Tantan have their own strengths in their respective markets and among targeted customers.

Tantan’s users are younger on average than core Momo’s users. And while core Momo is primarily focused on connecting people in a broader sense among larger groups and communities, Tantan is primarily focused on connecting people for romantic purposes. Momo is largely matured and Tantan is growing rapidly. Together, the group has a clear leading position in China’s open social market. Therefore, to solidify such a position where Momo remains a cash cow and Tantan remains a growth driver and soon-to-be profitable enterprise, strategic synergy will and should be a key priority.

The company took a prescient step in this direction when Tantan launched its own live stream service as a supplementary service to the core dating experience. Of course, this is a low-hanging fruit to pursue based on Momo’s significant experience in the area. And to Momo’s delight, Tantan’s paying user structure and performance revenue contributions are already decentralized and long-tail driven in comparison to the Momo live stream service. It allows the live stream service to flow directly flow with the core social experience which is what the company is trying hard to do with the core Momo app.

Closer collaboration should be enabled on the marketing and conversion front as well. As mentioned earlier, management has emphasized that user growth is its number one priority for Tantan in the short term. I’m confident that management is aware of the clear value to be derived in this area by enabling collaboration in top-of-funnel marketing efforts and conversion methodologies.

Now, the question is if these efforts are enough to provide Momo with a durable competitive advantage. In Momo and Tantan, the company clearly has the two most committed platforms focused on offline relationship conversions.

On the Q4 2020 earnings call, Wang Li said the following.

In the coming ten years we’ll see a continuous boom of China’s private consumption and it will be gearing up from a goods-driven model toward a service and new consumption-driven model… In the coming decade, we’ll also see phenomenal changes and advancements in communication technology and hardware devices. Moreover, with the rising personal income and education level, the world’s highest level of digitalization, and increasing focus on individuality, today’s younger generations are becoming increasingly open toward the idea of online dating and broader social products and services providing emotional companionship… It’s quite possible that we will see the cultural inflection point in the dating and social space within the coming decade. As a company that focuses on helping people build new relationships, we stand at a cross-section of all those trends.

But the social and dating industry is still an evolving market and a consistent stream of new entrants keep popping up.

Does Momo Have a Moat?

First, there’s the argument that network effects are as crucial as ever in dating apps. The more users an online dating platform has, the more valuable it is to new users since it makes the potential pool of partners larger.

And there’s empirical evidence of this. One of my favorite ways to spot an economic moat ex-ante is when there has been a prior situation where a well-capitalized competitor has given up competing. An example of that is when Facebook launched its dating service in 2018 which led the share price of Match Group (then still a part of IAC) to drop over 20%. Ever since, it has yet to capture any meaningful market share from any of Match’s subsidiaries.

An equally dominant competitor in China is Tencent which has tried to launch three separate dating apps in 2019: Dengyou Jiayou, Maohu, and Qingliao. Like Facebook Dating, none of these offerings have yet to gain meaningful traction.

I think the problem is in lack of commitment. The quirk of modern dating is that it’s a typically isolated activity from one’s other life aspects. That makes it difficult for any player with a periphery offering to jump in and scoop market share in a big way, even if it’s a social media giant.

Although the open social and dating market is still in a progressive stage, I find it likely that Momo and Tantan have reached the stage at which dominance itself will be a defender from new entrants. As Yan Tang said on the Q3 2018 earnings call:

Because if what a user is primarily looking for is to find someone new to interact with, it’s unlikely for that user to be closing between Momo and a short video app or a music app. We think that user is more like need to be choosing between Momo and Tantan.

But this moat is not invincible and will always be subject to user satisfaction. Continued growth and maintenance of the economic moat will be attributed to an active management that intends to continuously innovate and introduce new social features and upgrading current features that differentiate Momo from its competitors. As soon as that stops, the moat will evaporate.

In recent years, Tantan has put emphasis on strengthening the core dating ecosystem by attracting a much higher percentage of female users by tweaking their marketing approach. This is a great way to widen the moat.

Nonetheless, one competitor that came along in 2015 that has successfully pulled off the differentiation strategy is Soul. On Soul, strangers can only start chatting with each other without knowing each other’s appearances with the sole purpose of finding a soul mate. Using personality tests, the app generates a pool of users with the best match for users to choose from by only letting them know the personality match score. Soul has been growing fast and is rumored to confidentially file for an IPO in the U.S that could take its valuation over $1 billion. Whether Soul with its slightly distinctive purpose from Momo and Tantan will be in direct competition is yet to be seen.

But competition from new entrants is not the only risk to the business.

Being a technological media business operating in China, regulatory risks are very real and are not to be neglected. Tantan was temporarily pulled from app stores for a couple of months in early 2019 after a probe into the app being used primarily as a hookup app and for some of its female users to be showing “inappropriate” clothing. Since the incident, both Momo and Tantan have made efforts to downplay their reputations and stress their ability to make lasting personal connections. Collectively, Momo and Tantan now have a dedicated team of over 1500 employees overseeing the content on the platforms to ensure compliance with PRC laws and regulations. Higher regulatory risk is simply the nature of business if you’re a Chinese media company labeled as an internet content provider.

Valuing Momo Inc.

Valuing Momo with a high degree of certainty is not an easy thing to do. We work with many moving parts, unpredictable growth rates, and unstable margins.

Our best approach here is simply to remain conservative. But, as we will soon discover, we don’t even have to be slightly moderate in our assumptions for Momo’s future prospects for us to conclude a comfortable margin of safety in today’s price of the company.

Our valuation will, of course, be highly dependent on our assumptions for Momo’s future revenue mix. Based on this write-up, I have my story made up of the future business which undoubtedly differs from management’s story and likely your story as well.

Revenues

First, I’m wary of going with the assumption that the live streaming business will get back on track in terms of its historical growth on the back of the structural reforms made to the segment last year. Management seems confident that that is the case. But I think the live stream competition is simply too fierce and it will be diabolically hard to compete with competitors that make live stream their priority as opposed to it being a secondary functionality in Momo’s social offering. If management ends up succeeding in its way towards a long tail content ecosystem—breaking the artificial barriers between live video service and value-added service—then consider it a rewarding bonus to our valuation.

Rather, I will assume that the live stream business continues its descent over the next ten years after which the segment will remain an insignificant part of the company’s revenues in comparison to value-added service which will counteract to become the company’s dominating revenue source. For Tantan’s newly created live stream product, we will assume no change in revenue from the 2020 level. Having value-added service as the company’s eventual main revenue source will cement the market story of Momo being a social connectivity product as opposed to its current reputation of being a live streaming product.

To next forecast the more tricky growth issue of value-added service, we’ll need to dive into the unit economics.

Broken down by apps, I will assume that core Momo has largely reached maturity for new users but that the company through innovative social experiences will be able to recover dormant users of which Momo has a large pool. Along with population growth and rising internet penetration in China, I assume a constant growth in MAUs of 3% annually. I also assume the rate of paying MAUs to remain at its five-year average of 8.7% (current figures for paying users include users who spend money on live streaming which we assume will gradually move to value-added service).

For Tantan, I will assume that it can at least double its MAUs from its current level of 35 million to 70 million over the next five years—14.9% annually—after which the growth rate will gradually slow to 3% over the following five years. Currently, the ratio of paying MAUs is 10.9%—slightly below the rate of Tinder. We assume the rate will remain at its current level.

Now to the potential of price hikes. Both Momo and Tantan VIP memberships are currently priced at CNY12 monthly of which Tantan recently introduced an SVIP membership priced at CNY30. In comparison, Tinder’s lowest-tier premium solution, Tinder Plus, is currently priced at $19.99 monthly. While the purchasing power of Western markets justifies a higher price, this difference is immense.

To account for the difference in purchasing power, let’s rock the boat and do as The Economist when they invented the Big Mac Index. Using the implied exchange rate from the price difference of a Big Mac in any two countries, The Economist uses “burgernomics” to determine whether a currency is relatively overvalued or undervalued by comparing it to the real exchange rate.

According to the latest figures, a Big Mac costs CNY22.4 in China and $5.66 in the U.S. The implied exchange rate is therefore 3.96. Using this lighthearted logic, Momo and Tantan should eventually be able to price their low-tier VIP membership at ~CNY33 ($19.99 / 3.96 * the USD/CNY exchange of 6.46). We, therefore, assume that membership prices will grow by 10.6% annually over the next ten years after which prices will grow by an inflation rate of 3%.

Conclusively, we assume that value-added service for core Momo will grow at 13.6% the next ten years from its current base of CNY3.74 billion. Concurrently, value-added service for Tantan will grow at 25.5% over the next five years from its current base of CNY1.37 billion from which the growth rate will gradually slow to 13.6% the following five years. Meanwhile, we assume that live video service will decline by 10% annually and that mobile marketing, mobile gaming, and other services will grow by 3%.

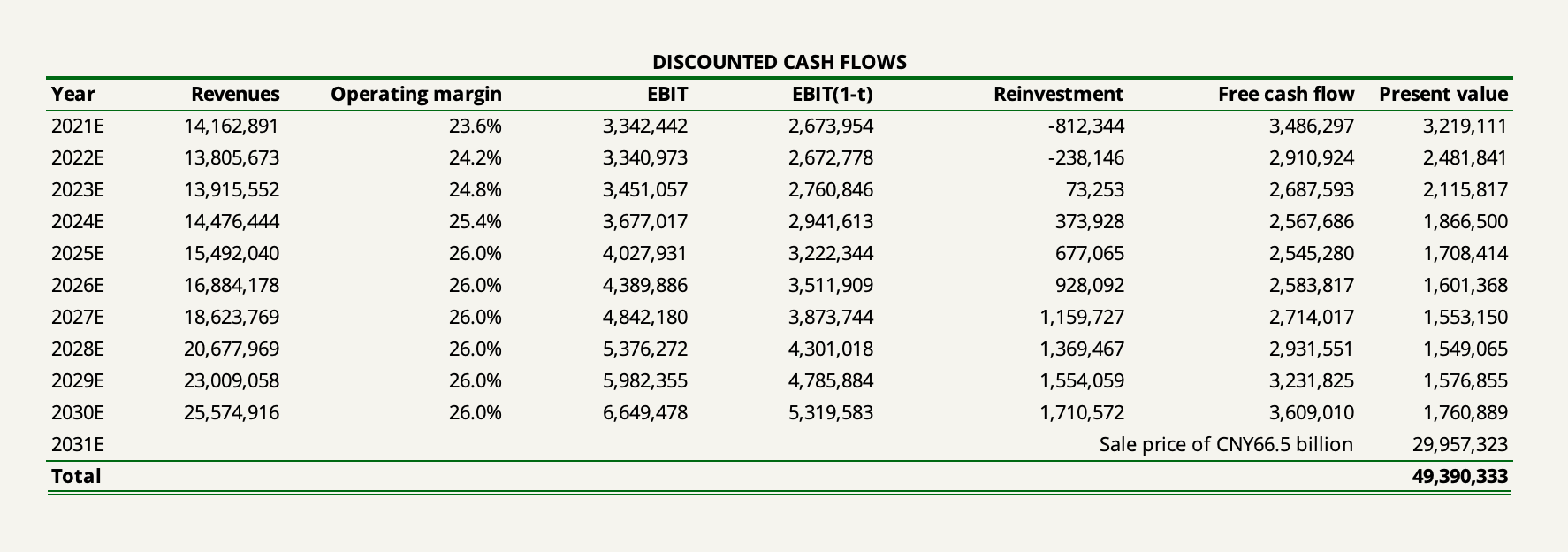

Next, Operating Margins.

Using the ROIQ model, I’ve adjusted Momo’s earnings to better reflect economic reality. Due to the company’s nature of business, a lot of its investments flow through the income statement in the form of R&D and advertising which distort the company’s historical earnings picture. I’ve therefore capitalized Momo’s R&D expenses using a 6-year amortization schedule on the basis of the company’s R&D expenditures going back 9 years. Meanwhile, Momo’s advertising expenses are capitalized using a 2-year amortization schedule also going back 9 years. This exercise raises Momo’s invested capital base while only charging the amortization part of the research and brand advertising assets created to the income statement. The effect is that it raises the company’s EBIT margin in the fiscal year 2020 to 23.1%.

Now, projecting the difference in economics between Momo’s live video service and value-added service is difficult. But one thing is certain: as the company’s revenue mix changes, so will the operating margin.

Purely digital services is a high-margin business with a practically zero marginal cost. As for Momo, the 47% gross margin is heavily weighted by the company’s revenue sharing activities to broadcasters and talent agencies. In comparison, Match Group’s gross margin was 73.4% in the fiscal year 2020. But as we would expect Momo’s live video service segment to constitute an increasingly insignificant part of the company’s operations over the next ten years, we should also expect the gross margin to increase.

However, there are a few reasons from which I believe operating margins will improve over time—mostly driven by Tantan. First, marketing and user conversion efficiency will improve as a natural consequence of stronger network effects as the platform increases its MAU. Relatedly, the company’s current operating margin is weighted down by Tantan’s current unprofitability which will likely soon arrive in profitable territory. Second, our assumed price increases of memberships and adjacent value-added services will provide economies of scale.

To not get ahead of ourselves here, I will make the assumption that Momo’s EBIT margin will gradually increase to 26% over the next five years.

Discounted Cash Flows

My remaining assumptions are:

- An effective tax rate going forward of 20%.

- A marginal sales to capital ratio of 1.5 which determines the company’s reinvestment needs as it grows. Momo’s sales to capital ratio was 3.1 in the fiscal year 2020. I assume a decreased reinvestment efficiency going forward to account for contingent acquisitions and higher invested capital needs. (Momo has grown its cash position invested in marketable securities a lot over the past five years.)

- A cost of capital of 8.3% using an opportunity cost of equity of 10% and an after-tax cost of debt of 1.26% weighted by the company’s current capital structure.

- The business is sold in year 11 at 12 times EV/EBIT—a low estimate for a growing Chinese tech business.

We can thus derive the following cash flow table:

By adding non-operating assets in the form of excess cash and marketable securities of CNY10.5 billion and subtracting debt of CNY4.9 billion, we arrive at an equity value of CNY54.9 billion. Converted to USD and divided by shares outstanding, it equals a value of $41.3/ADR.

Compared to Momo’s closing price yesterday at $14.2/ADR, it’s almost a 3x upside giving us a significant margin of safety. Especially so since our valuation largely rests on the assumption that the company’s live stream business—its cash cow—will be a disintegrating business over the next ten years.

We’ve Seen This Situation Before

Momo is obviously cheap. But this isn’t the only Chinese social tech business I’ve found to be trading for pennies on the dollar. At the beginning of last year, I found such a company in SINA Corp, the controlling company of Weibo of which SINA’s Weibo stake was worth almost double SINA’s own market cap. The price was clearly a bargain and I invested at $39/ADR. It was obvious that management thought the same thing, engaging in extensive buybacks and mentioning the cheap share price in multiple earnings calls.

Only 8 months later, founder and CEO Charles Chao holding 58.6% voting power of the company, decided to go ahead and take advantage of the deal Mr. Market had presented for some time. SINA was taken private at $43.3/ADR in a buyout by Charles Chao’s holding company, New Wave MMXV Limited. We made a measly 9% from a high-conviction investment meant to span many years.

In addition to business risks and regulatory risks, this is a stakeholder risk to the investment thesis because the same situation is present with Momo. Through his holding company, Gallant Future Holdings Limited, Yan Tang owns 20.7% of Momo’s shares and holds 71% voting power. Of course, this is not a bad thing and not uncommon for a founder-led tech company. But the difference between SINA and Momo and their western parallels is that Western markets rarely let their tech companies trade so cheaply through long periods of time. That coupled with the fear of major ADR delistings in the U.S. as a calamity from the U.S-China trade war presents the increased risk of cheap Chinese companies such as Momo being taken private at unfavorable prices.

I have very little idea of whether the story of Momo will turn out the same, but the reality is that the market might go ahead and price the company even cheaper in the short term. A go-private deal pushed ahead by a major voting shareholder could be a source of permanent capital loss. But, considering the attractiveness of the investment, we are happily willing to invest with Yan Tang and the capable leadership team at Momo for the long term—as long as possible.