It’s now the year 2020 and earnings season is approaching. So I decided to take a look at a company which 2019 annual report I’m very excited to read—and that’s Kraft Heinz.

As you probably know, Kraft Heinz has been hit by a series of troubles and the market value has experienced some terrible few years falling 11% in 2017, 44% in 2018, and another 30% in 2019, from a price of $87 to today’s price of $30.60. Taking account of dividends paid, investors have since the beginning of 2017 suffered a total loss of 64% (59% including dividends).

The biggest blow came on February 22 last year when Kraft Heinz shocked investors with four terrible news in its earnings report: disappointing operating results, SEC investigations into the company’s accounting practices, a massive impairment of goodwill and intangible assets, followed up by a 40% cut in dividends. The stock price dropped 25% on the day after the announcement and until today remains unchanged in light of consecutively disappointing quarterly results in the first three quarters of 2019.

Why is Kraft Heinz so interesting to investigate? I mean, it’s certainly not unheard of for a company to suffer large, multiple hits in a short period of time.

The reason why Kraft Heinz’ crisis is especially noteworthy is that the majority of ownership (and Board) at the release of the 2018 earnings report was held by Berkshire Hathaway with 26.7% and 3G Capital, a renowned Brazilian private equity partnership known for its ruthless focus on efficiency and cost-control, with 29%. Since then, 3G Capital has sold about 9% of its stake.

The Kraft Heinz Company is a result of a $63 billion merger in 2015 that the two major shareholders backed in an initial joint deal by bringing together H. J. Heinz and Kraft Foods, two of the biggest names in the food business.

The merger was viewed as a masterstroke and, given the notoriety of the two investors, guaranteed to succeed. But even though the Board has replaced the CEO and claims to have brushed up its accounting practices, investors are increasingly losing patience and confidence that it will. Hence, the share price.

***

At Junto, as you may know, we care about operations and intrinsic value – not price action. Obviously, it seems the value of the company has taken a hit due to the same reasons the price has tanked. However, the real questions remain: What is the intrinsic value of Kraft Heinz going forward, and is the depressed price at a discount to that value?

That’s why I wanted to take a closer look at the core of the company in light of the company’s ongoing restructuring and strategy going forward.

So in this write-up, we look at Kraft Heinz’s history, current operations, prospects of its business, and the changing dynamics of the consumer packaged goods industry. Lastly, we will attempt to value the company and determine whether the current price constitutes an investment opportunity.

Before taking a look at the business’s current operations and management, it would be fitting to first understand its history.

Back Story

The original H.J. Heinz company is the older of the two companies making up Kraft Heinz. The ketchup company was founded by Henry John Heinz, son of German immigrants, and traces its roots all the way back to 1869. From the beginning and throughout the entire company history, Heinz Tomato Ketchup has been the company’s most iconic brand.

In the centuries after its founding, Heinz expanded its food selections, became the top-seller of ready-to-eat meals and baby food under the Great Depression, and expanded its international presence through brand acquisitions and plant developments. Today, the strong brand behind Heinz’s Tomato Ketchup claims more than 60% market share for ketchup in the U.S. and 80% in Europe.

On February 14th, a press release announced that H.J. Heinz was being acquired by a consortium owned by Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital for $23 billion.

***

Kraft traces back to 1903 when a Canadian immigrant named James L. Kraft together with his brothers started a wholesale door-to-door cheese business in Chicago. The company quickly sold 31 varieties of cheese and expanded into other dairy products.

The company was acquired by National Dairy Products in 1930 which later got acquired by Philip Morris in 1988. Philip Morris then acquired Nabisco Holdings in 2000 and integrated Kraft and Nabisco into Kraft General Foods which was later sold off as an independent company in 2007.

Independently, Kraft quickly went on an acquiring spree of its own, snatching up the French food company, Groupe Danone for $7 billion and British Cadbury in a grand deal of $19 billion. In 2012, Kraft was divided into Kraft Foods Group and Mondelez International.

Then in 2015, Kraft Foods Group was merged in a massive deal with H.J. Heinz led by the Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital investors. The merged entity that is now Kraft Heinz created the third-largest food and beverage company in North America and the fifth-largest in the world, holding more than 200 iconic brands.

While grand, the deal was a big bet on conventional staples of the American cupboard, even as consumers started shifting (and continue to shift) away from processed foods. It was also a bet on 3G Capital being able to succeed with its infamous cost-cutting strategy based on zero-based budgeting that the private equity group had so succeedingly implemented with Anheuser-Busch InBev and Burger King before it merged with doughnut chain Tim Hortons to form Restaurant Brands International. The restructuring activities together with synergies achieved between Kraft and Heinz was projected to yield $1.5 billion in annual cost cuts, setting a very bright future for the company’s cash generation and growth opportunities.

However, while investors expected relatively smooth sailing, things so far did not turn out as planned. While management focused on aggressive cost-cutting, it seems they could not adapt fast enough to meet consumer demand for healthier, fresher products and the increasing competition from retailers themselves in the form of cheaper private labels. Revenue growth suffered and margins, while shortly improved, brought other problems with it.

Then on February 22, 2019, Kraft Heinz announced four terrible news in its 2018 earnings report:

- Stagnating growth: The tale was the same as in the company’s 2017 earnings; revenue growth remained unchanged from 2016-2018 coming in at $26.3 billion. So did its operating income which quickly rose from $5.74 billion in 2016 to $6.20 billion in 2017 only to fall back to $5.80 billion in 2018, causing the operating margin to drop from 23.5% to 22%.

- SEC investigation: The company disclosed an SEC subpoena related to an investigation into its accounting practices for procurement procedures and impairment testing. The investigation recently revealed serious misconduct made by employees in the procurement area.

- Goodwill and intangibles impairments: The company announced impairment losses of $15.40 billion in certain reporting units, primarily U.S. Refrigerated and Canada Retail, and certain intangible assets, primarily the Kraft and Oscar Mayer brands. These units basically originated from the Kraft part of the Kraft Heinz merger indicating quite a significant overprice paid for Kraft at the merger.

- Dividend cut: The company cut its dividend per share from $2.50 to $1.60, partly to finance repayments of its large $31 billion debt pile.

As you already know, the market reaction was a tanking share price. And since it’s now almost a year (and three quarterly reports) later, how has the story unfolded in the meantime?

- Restatements of three-year annual reports: On May 2, 2019, management and the Board concluded the annual statements for the years 2016 and 2017 as unreliable as a result of the company’s internal investigation into its accounting practices. Therefore, the company revised statements for both years. The restatements revealed underestimates of cost of goods sold totaling $208 million. While these figures are somewhat immaterial, they did reveal something about the company’s accounting problems.

- New CEO: On April 22nd, the company appointed Miguel Patricio, former Anheuser-Busch InBev global chief marketing officer and renowned ‘marketing wizard’, to take over as CEO from Bernando Hees.

- Late report and further impairments: Kraft Heinz was late to report its results for the second half of 2019 and took further impairment charges to poorly performing brands, including $474 million tied to Velveeta, Maxwell House, Miracle Whip and three other brands as well as a $744 million charge after lowering sales forecasts for several of its international businesses.

- 3G Capital share liquidation: 3G Capital has sold approximately 9% of its stake since the 2018 earnings announcement.

Management has been candid about the outlook for the fiscal year 2019, of which the 4th quarter probably will be revealed next month, as gloomy. While results for the first half of 2019 showed disappointment, 3rd quarter results slightly beat expectations, albeit with negative organic revenue growth.

And here we are on January 8th.

What we need to establish now to be able to do to a rational valuation of Kraft Heinz is whether the company really is in as deep trouble as perceived and whether the company under the new management led by Miguel Patricio will be able to stabilize the business and lay the groundwork for a brighter company future.

A Closer Look at the Business

Kraft Heinz has a huge debt overhang.

Kraft Heinz has a massive $31 billion debt pile that needs to be widdled down by either cutting dividends for a few years, selling off assets, or both.

As long as the company’s operating results (excluding amortizations) and stable cash flows are not in danger, the debt should not pose any side effects. However, it’s vital that the company does not go down a negative spiral of decreasing competitiveness and, consequently, falling margins since the vast part of the company’s asset side depends on intangible assets, and additional charges could potentially spell trouble for management in selling off units.

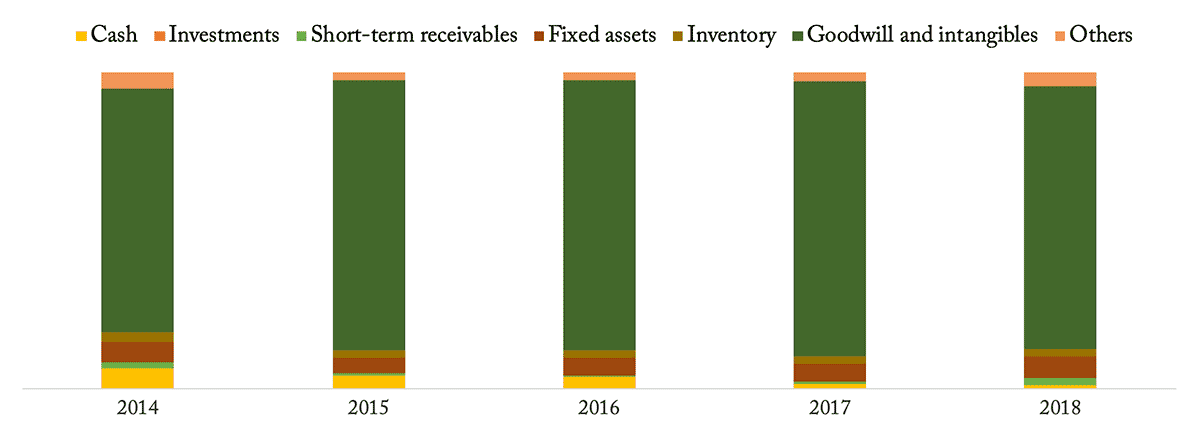

Just take a look at the asset composition even after taking major impairment charges in 2018:

Considering the company’s past mishaps of accounting irregularities, we need to consider the possibility that management may need to slowly charge additional impairments. According to the 2018 annual report, about $29 billion worth of brand goodwill is at heightened risk of impairment.

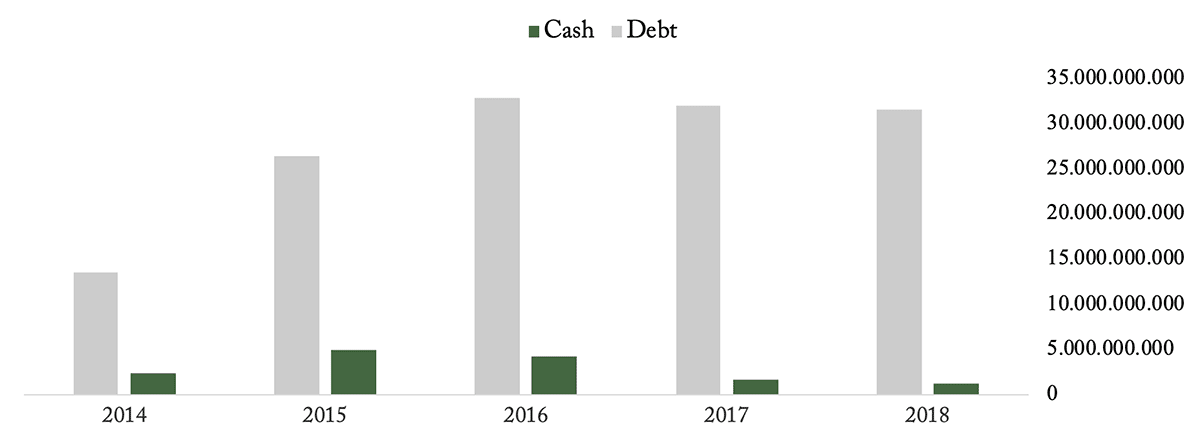

Meanwhile, the company’s cash coffers have slowly decayed. A big part of the reason is that the company in 2018 stopped its securitization and sale of receivables to finance working capital with debt instead:

According to the latest Q3 2019 report, the debt pile remains about unchanged from the end of 2018. This debt overhang indicates a strong vulnerability to an increase in interest rates or a few bad years of operations since Kraft Heinz spends almost $1.3 billion on interests a year.

Let’s look at profitability.

Due to restructuring activities, non-cash benefits for taxes, and extraordinary charges, Kraft Heinz’s net income and operating cash flows have been fairly volatile since the merger in 2015, and it’s difficult to gauge a normalized level of profitability coming out on the other side.

Two questions are important in this situation: How much does the company earn on its core operations, and, due to its smaller size, how much can we expect the company to reinvest in the business to maintain its operations?

If we take a look at the company’s operating income (excluding amortization but including depreciation), Kraft Heinz does really well earning about $5.7 billion in 2018, $6.1 billion in 2017, and $5.6 billion in 2016. If we assume a long-term average tax rate for domestic and international operations of about 25%, that would comprise a net operating profit after tax of about $4.3 billion as operations currently stand.

On tangible assets of $18.3 billion (as of Q3 2019), that’s a hefty return. And taking only the company’s property, plant, and equipment of about $7 billion, it’s very impressive.

If Kraft Heinz continues to flatline revenues for a long time, can we expect the company to earn and grow these kinds of profits indefinitely? Probably not, and the market certainly doesn’t think so. Management expects a decrease for full-year 2019.

So to determine the long-term outlook for the company’s earnings potential, we need to first dive further by looking at the company’s competitiveness.

Kraft Heinz’s competitiveness is getting more uncertain.

As a function of Kraft Heinz’s strong brands and historical economic moat around these, the company has historically earned very high margins and still do. With a gross margin of about 35% and an operating margin of 22%, Kraft Heinz’s profit margins are much higher than peers such as General Mills and Kellogg.

But those margins are under threat from a trifecta of unfavorable circumstances:

- Smaller micro-brands better aimed at fulfilling consumer needs are nipping at the heels of big CPG-companies, and the trends change faster than they can react. Additionally, cheaper private-label competitors continue to put pricing pressure on the industry.

- Because of this increased competition and fast-changing consumer demands, there’s a significant chance that Kraft Heinz will need to increase its investments in marketing just to sustain its current position. This is an indication that the company will probably need to ramp up its investments in marketing and innovation over the long-term.

- Continued consolidation of retail customers and increased competition from these retailers’ own private labels have increased their buying power. This results in sustained increases in supply chain costs for CPG-companies such as Kraft Heinz since customers progressively demand improved efficiency, lower pricing, more favorable terms, and increased promotional programs.

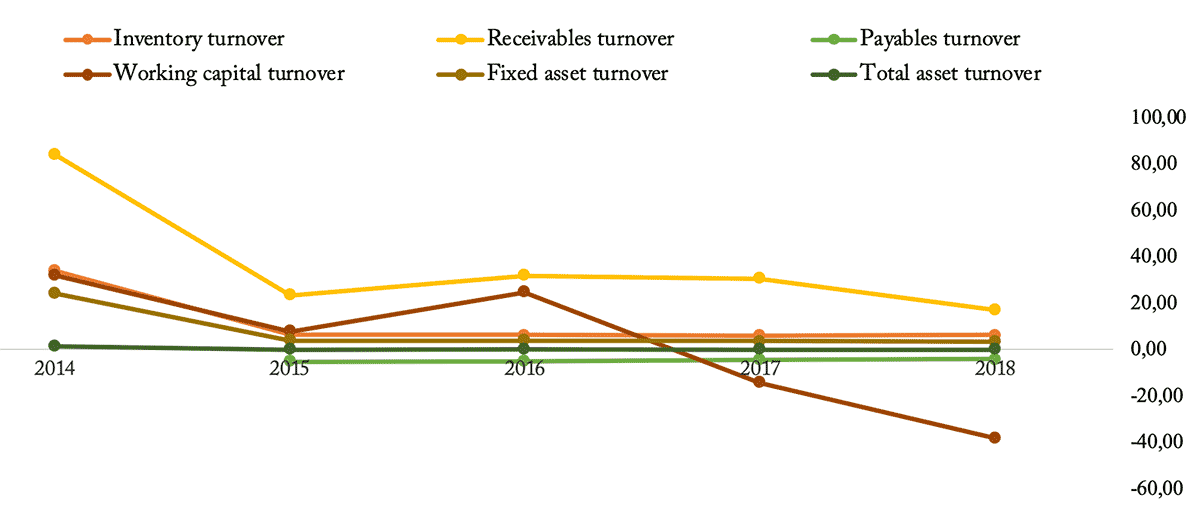

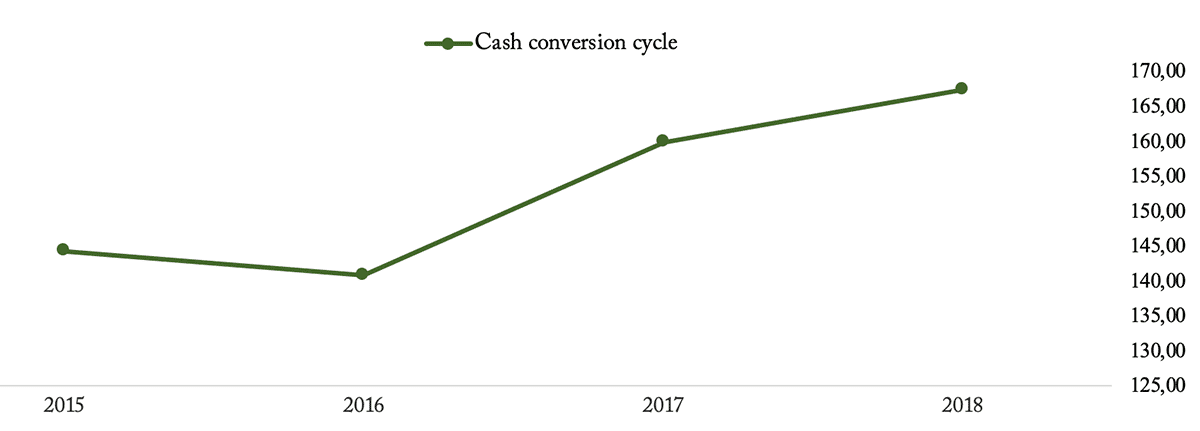

The last factor involving increased supply chain costs has already been reflected in Kraft Heinz’s liquidity cycle for the past years. While turnover ratios on all fronts have suffered, the cash conversion cycle has gone up putting pressure on the company to finance its ongoing operations without increasing debt. 2014 figures are included to reflect the change from the merger:

Does restructuring destroy innovation?

On February 22, 2019, The Economist wrote the following on the problems at Kraft Heinz:

Consumers are yearning for healthier, less processed food. Supermarkets are giving fresh produce more space, at the expense of tinned products. And the rise of online grocers like Amazon is further disrupting distribution channels.

Since the merger, zero-based budgeting was at the core of 3G’s and the management team’s effort to unlock value by implementing large-scale cost improvements to boost profit margins. However, have these activities significantly impaired the company’s ability to innovate to keep up with the changing landscape? And are the accounting irregularities a result of this intense cost-focus?

That’s a tough thing to measure but it certainly is the sentiment around the company’s problems. As a paper from September 29 in the Harvard Business Review suggests, this inability to innovate was, in part, the result of such intense cost-cutting focus, not just financially but behaviorally:

For most people, company restructuring initiatives represent a threat, triggering a strong ‘survive’ response in the brain. Fear, uncertainty, and anger fuel distrust in management and narrow all focus to eliminating the threat — leaving no capacity for creative ideation.

The authors, John P. Kotter and Gaurav Gupta describe how such a behavioral response runs down through the rest of the organization, triggering a “freeze response, fuelled by despair and hopelessness”.

Certainly not a good governing situation to be in. But to be fair, Kraft Heinz’s main competitors have had mixed results with their attempts to spur innovation and acquire nimbler micro-brands for the past years. While Mondelez has been able to improve its margins while introducing new products, other competitors have snatched up smaller brands, often at high prices and with mixed results. Shopping sprees at Campbell, ConAgra, and General Mills have made those companies more levered than Kraft Heinz.

The cost-cutting spiral’s impact on innovation and investment should be on track to change with Miguel Patricio who wants to instill a philosophy of continuous improvement as a much more consumer-driven company into the organization. He’s known to be a guy that essentially views creativity as investment.

However, I only partly buy into the fact that Kraft Heinz’s current problems can be totally blamed on lack of investment. It seems that growth and margin pressures are not only specific to the company but is the result of a bigger, pressuring, secular trend in the CPG industry. We need to think about whether this trend is permanent or whether big, traditional CPG companies will manage to adapt and preserve the moat around their brands.

Let’s discuss how this is likely to play out.

Major Factors Governing the Long-Term Outlook

The Brand as a Competitive Advantage

In my last article, I wrote about how modern times of information abundance are substantially affecting entire industries and how brand loyalty is changing across consumer goods industries.

In the article, I described how brands essentially consist of two elements; trust and signaling, where brands basically comprise a substitute for incomplete information consisting of these two elements. If information is scarce, people flock to trusted brands, and if it is abundant, people flock to peer-reviewed preferences. And since we live in times where information is predominantly abundant, consumers to a lesser degree defer to brands with an overweighing trust element when making purchasing decisions.

This matters a lot to Kraft Heinz, because in the CPG industry trust weighs more than signaling in a given company’s branding moat.

In the article, I wrote that..

… due to information abundance, the companies that used to have this competitive advantage are starting to lose market share to “micro-brands” better equipped to meet niche and ever-changing consumer tastes. This trend is stronger than might be perceived in everyday life precisely because internet communication is highly fragmented, and compared to mass-appeal brands, the advance of micro-brands is nearly invisible to the real world.

Brands are normally one of those moats that have the longest staying power and strong brands can last for very long, often stretching over many decades. Is that now going to go away in the CPG industry?

While weaker brands will be challenged, I do think the strongest brands will largely endure, albeit with smaller growth prospects. How else can Kraft Heinz and the best peers earn those high returns on tangibles and margins on revenue? To say that brands are becoming worthless and will be replaced by private labels, micro-brands, and Amazon would be asinine.

However, it does seem that big CPG brands are not as predictable businesses as they were in times where massive economies of scale could be achieved using Mass Media advertising. I don’t think incumbent moats of big brands are being filled, but due to changing consumer needs and information abundance, they definitely have become more uncertain, posing a big challenge for investors to predict the long-term outlook for CPG businesses.

I think a wise thing for management to do to bring down its debt is to sell off many of its weaker brands before the effects of the changing consumer landscape sets in more substantially.

Distribution Networks

I think a big part of the way CPG companies historically created consumer brands, along with the aforementioned “marketing monopoly” by taking advantage of Mass Media, has to do with how companies have dominated the supply chain from brand to supermarket shelf. By efficiently developing huge distribution networks, and in the case of Kraft Heinz very efficient and nimble supply chain operations, the biggest CPG brands today in part are so strong because of their past ability to quickly fill up space and awareness on retail shelves.

3G Capital wanted to milk that once again. One of the big ideas behind the Kraft Heinz merger was that it could allow the combined company to expand Kraft’s iconic brands internationally through Heinz’s already established international distribution channels and infrastructure outside of the U.S. from which about 70% of Heinz’s sales originate. Meanwhile, the Heinz brands could ride on Kraft’s robust presence in 98% of American homes.

Yes, big CPG companies such as Kraft Heinz can continue to invest in expansion and efficient distribution which will not go away as a competitive advantage.

However, the problem now is that the internet and changing competitive landscape have reduced distribution (and information) costs closer to zero, while the threat from customers has gone up, which in the process has eroded the ecosystem which largely allowed brands to be a basis of competitive advantage.

I think the growth effects from distribution investments as a means to generate growth will be mitigated by this changing landscape, setting a limit on Kraft Heinz’s possible long-term growth rate.

Organizational Culture Integration

On April 19, 2018, Forbes writer Russell Raath wrote an article on the Kraft Heinz post-merger integration and how the company’s culture is a key risk factor in that process.

The vague and unmeasurable nature of “culture” is often an overlooked or misunderstood factor in post-merger integrations. Since culture does not directly show up in the numbers or statements, it’s easy as an investor just to sweep the question aside and trust management to handle it.

But since we as investors are interested in how a company will perform over decades from now, this question is vitally important.

The job of integrating the culture between two companies becomes immensely more difficult if it at the same time involves implementing an intense cost-cutting strategy. Remember the discussion on how restructuring and innovation can be contradictory?

As Russell Raath writes:

When I’m being measured by how much cost I have taken out, it’s not hard to see why I’m not going to invest in my people, or the office or a new printer. This creates an environment, despite any synergy savings, where people simply don’t want to be.

Unfortunately, it seems Kraft Heinz fell into this trap.

So one of the tasks going forward, if not the most important, is to do the things that help to build a great, high-performing culture at a company that will win. With the company’s recent publicized blows and the insertion of Miguel Patricio as CEO, my guess is that Kraft Heinz will get this right over time. Although it might have taken longer than expected.

Putting a Value on Kraft Heinz

I’m into using simple math when doing valuations. In fact, you probably will not see any sophisticatedly complicated mumbo-jumbo spreadsheet valuation models using a bunch of greek letters here on Junto, except on rare occasions.

When that happens, the analysis in question will solely be a learning case, not a possible investment. Our principle is that as soon as we need to bring in the big spreadsheet to figure out the value of a company, the subject is out of our circle of competence and we shouldn’t invest. If the value does not jump at us, it’s not for us.

So how should we go about valuing Kraft Heinz in light of what we have learned?

I think a fair starting point would be to take the company’s current annual level of net operating income (after tax) which we determined to be about $4.30 billion using a long-term international tax rate of 25%.

Now, this income was based on Kraft Heinz achieving an operating margin of 22%. We learned from our qualitative analysis that there’s probably a small chance for this to be sustained. If we instead assume a long-term operating margin of 20% due to discussed market pressures, we arrive at $3.94 billion.

We’ll use this figure as normalized free cash flow to the firm.

Now, sharp readers might ask: “But doesn’t net operating income include depreciation? What about reinvestment in capital expenditures and working capital?”

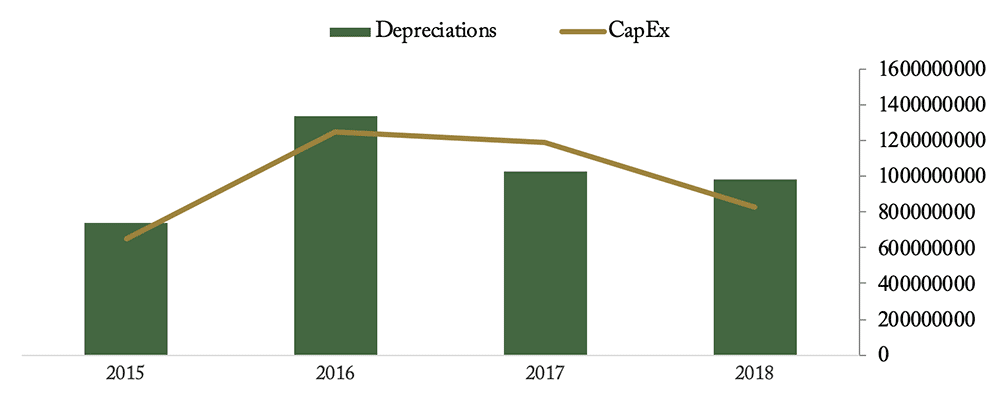

Take a look at the company’s capital expenditures and depreciation since 2015:

Considering the strong equality, a 4-year average depreciation level of about $1 billion, and the fact that the company depreciated just about hit this average of $1 billion in 2018, I consider the depreciation figure to be a good proxy for the company’s maintenance capital expenditures going forward. Additionally, the company has shown to be fairly consistent in working capital needs.

How about growth? In the case of Kraft Heinz, I think it makes sense to value the business under two scenarios: a no-growth scenario and a growth scenario.

The no-growth scenario:

In the no-growth scenario, I take the normalized free cash flow to the firm figure of $3.94 billion and stretch that into perpetuity. I discount these cash flows using what I consider a conservative long-term U.S. Treasury rate of 3%, about a percentage point above current rates (conservative meaning higher than current rates).

However, by discounting the cash flows using only the [risk-free] Treasury rate, we basically assume that we are 100% sure that these cash flows will actually materialize. Obviously, this is not the case. So how confident can we be in our cash flow projection?

Honestly, due to large uncertainties concerning to future outlook of both Kraft Heinz and the CPG industry, I can only place a 50% probability that I’m right in my assumptions and that Kraft Heinz can deliver such earnings over a long period of time. Therefore, we subtract our 50% uncertainty from our calculated enterprise value based on the aforementioned assumptions.

Consequently, we arrive at an enterprise value of about $65.70 billion. Net debt and minority interests by the 3rd quarter of 2019 amounted to $28.50 billion and our estimate of the no-growth equity value thus amounts to $37 billion, or about $30 per share.

The growth scenario:

How much growth can we expect in the long run for Kraft Heinz? Considering our discussion and factors governing the outlook, I expect little. My maximum, conservative estimate of a long-term growth rate would be about 5% for the next 10 years and 1%, below the expected inflation rate, into perpetuity.

And given a higher uncertainty around incorporating growth, I would increase the discount rate from the effective 6% (taking the 50% discount from value increases the “effective” discount rate from 3% to 6%) to 8%.

This two-stage valuation gives an enterprise value of $75.20 billion, and by subtracting net debt and minority interests, this amounts to an equity value of $46.70 billion, or about $38 per share.

And that’s how I would go about valuing Kraft Heinz taking into account our prior analysis of the story revolving around the business. To conclude, I can fairly say that my current perception of Kraft Heinz’s intrinsic value is somewhere between $30 and $38 a share.

Simply comparing to the current stock price of $30.60, the company looks fairly valued even after the large tank in market value and thus we will give it a pass for investment as of now.

Given the uncertainties involved and my own inability to confidently assess the future durability of Kraft Heinz’s economic moat as resistance to a gloomy industry outlook, we would require much of a margin of safety in the price before being willing to add the stock to the Junto investment portfolio.

Now, you might ask: “but wasn’t the 50% discount to the no-growth value a margin of safety?”

The answer is no. The equity value calculated taking the 50% discount is the intrinsic value I estimate based on my perception of the uncertainty behind my understanding and thus the risk of those cash flows materializing. If I placed a higher certainty on my understanding, the intrinsic value would be higher. Therefore, before being willing to invest, I would need an additional discount in price before classifying it as an opportune value investment.

In hindsight, the August 2019 low of $25 a share would perhaps have been a good opportunity to buy into with a fractional position. We missed that. Now the company goes on our watchlist, and if the price goes into attractive territory again or if other facts suddenly change my perception, I will take another look.