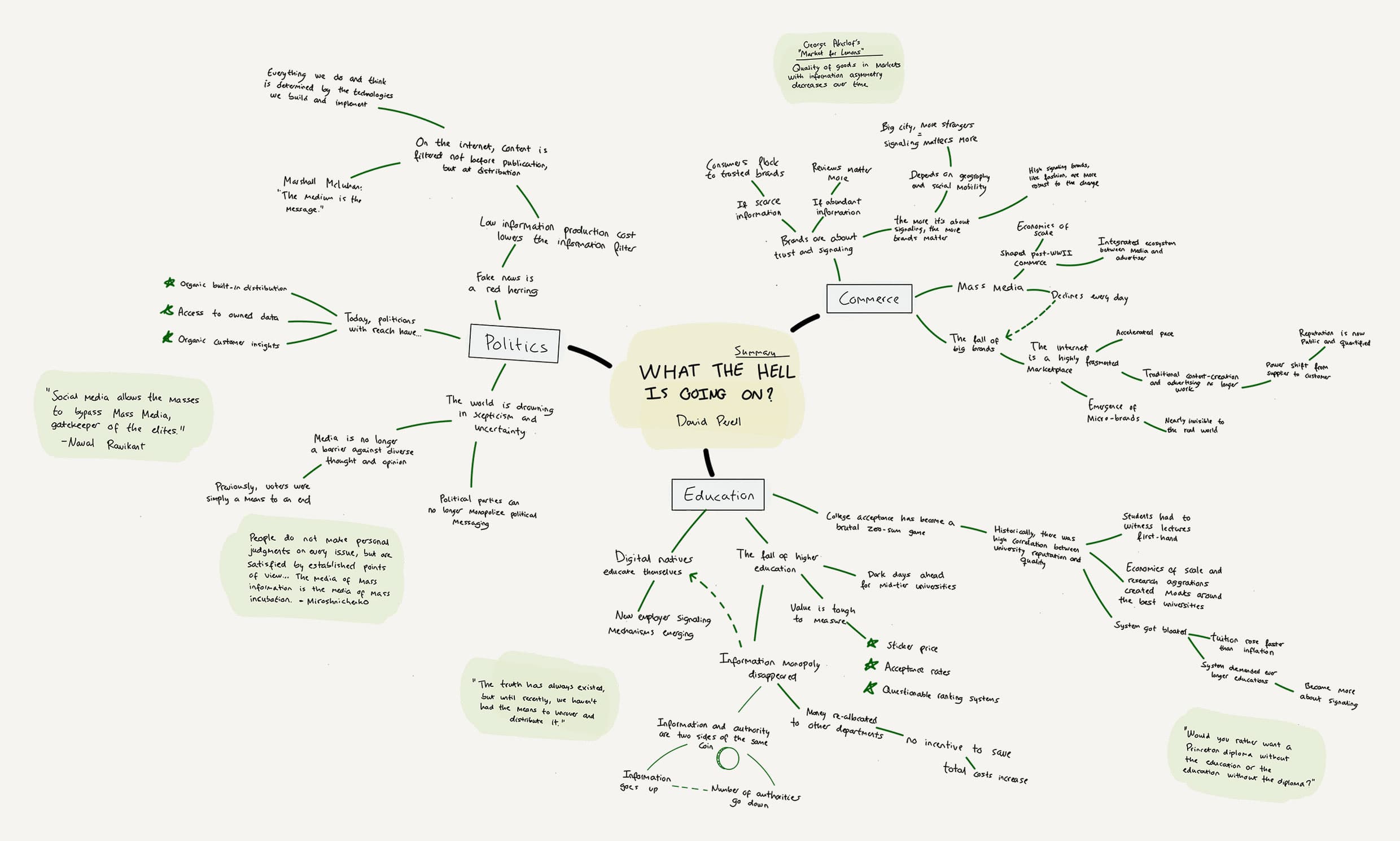

I recently read David Perell’s long-form essay, What the Hell Is Going On?, about how history’s movement from information scarcity (the Mass Media era) to information abundance (the Internet era) has changed entire industries, and how new mediums change how we think and act in society.

I found it brilliant and thought-provoking, so I figured I’d publicize my personal notes and mind map on the subject.

If you have a strong wish not to gain any enlightenment on how to understand and adapt to our current digital environment, I recommend you avoid reading Perell’s essay. If you do wish to learn how to reap its rewards, I recommend you absorb the entire thing.

From an investing point-of-view, I find his essay vital, especially as it relates to how different durable competitive moats for businesses thrive or break down in the new “information abundance” age.

Perell’s main argument is: The world has changed from information scarcity to information abundance and the effects are evident in every corner of society. Notably in commerce, education, and politics.

Foresight #1: Commerce will be quirkier.

Across consumer goods industries, brand loyalty is changing. To know why that is, we need to break brands into its basic two elements: Trust and signaling (and beneath that, there’s Pavlovian association, social proofing, etc). Brands are essentially a substitute for incomplete information consisting of these two elements.

According to Perell, brand loyalty based on trust is dying because the information in society has transformed from scarce to abundant. If information is scarce, people flock to trusted brands, and if it is abundant, people flock to peer-reviewed preferences. The argument is that since reviews are now available at people’s fingertips and reputation is public and quantified, consumers no longer defer to brands with an overweighing trust element when making purchasing decisions.

Coincidentally, I read Perell’s essay at the same time as I was reading Kraft Heinz’s 2018 annual report, and I found this insight to be very helpful as a big-picture perspective of the changing dynamics of consumer preferences in the CPG industry. In the CPG industry, trust weighs more than signaling in a given company’s branding moat. Consumers often buy a certain brand of cream cheese because they trust its taste and care not to save a few cents on a cheaper but uncertain choice. As in the case of the Philadelphia brand, it has historically earned the consumer’s trust through countless brilliant advertising using Mass Media communication channels. Consumers have learned to know the product, taste, and values and wouldn’t risk trying other, albeit cheaper, alternatives. The advantage of participating in the Mass Media ecosystem has given big CPG brands a large, sustainable moat with fat margins.

However, due to information abundance, the companies that used to have this competitive advantage are starting to lose market share to “micro-brands” better equipped to meet niche and ever-changing consumer tastes. This trend is stronger than might be perceived in everyday life precisely because internet communication is highly fragmented, and compared to mass-appeal brands, the advance of micro-brands is nearly invisible to the real world.

I have published my analysis of Kraft Heinz in a write-up. The main thing I’ve learned is that strong brands in the CPG industry are not as predictable businesses as they were in times where massive economies of scale could be achieved using Mass Media advertising. I don’t think incumbent moats of big brands are being filled, but they definitely have become more uncertain, posing a big challenge for investors to predict the long-term outlook for CPG businesses.

On the other hand, brands, where signaling is the overweighing element (eg. luxury brands), might turn out stronger. Signaling brands are context-dependent and thrive in environments with high geographic and social mobility. As Perell writes:

When mobility is high, information asymmetry is the norm. As a result, we use heuristics such as brand associations to gauge strangers. Just consider the differences in behavior between big cities and small towns. Big cities are full of strangers, but small towns are brightened by hugs and handshakes all the way down. In small cities, where everybody already knows each other, the utility of signaling brands is diminished.

It’s a good example of the urbanization that’s happening on a global basis. Meanwhile, social media interaction has given rise to signaling becoming ever more evident. This might help explain why luxury companies like LVMH have succeeded so significantly while traditional CPG companies have struggled in recent years.

Foresight #2: Education will be overhauled.

The information monopoly that universities once possessed has disappeared and digital natives now educate themselves.

Historically, there was a high correlation between university reputation and quality. But that was a time where high-quality teaching was limited by the reach of words, and the best professors could only teach hundreds of students at a time. Because the best universities could attract like-minded researchers and students, they could aggregate research and information to achieve strong network effects and economies of scale, enabling them to attract recurring revenue streams and ever-growing endowments.

That system worked until two things happened: the system got bloated and information became available at everyone’s fingertips.

Due to a mixture of growing U.S student debt, rising tuition costs, commoditized college degrees, and growing demand for longer and longer educations (what an economics professor at George Mason University, Bryan Caplan, calls credential inflation), people have started to question the value of the educational system.

College acceptance has become a brutal zero-sum competition, where an ever-expanding number of applicants fight for a limited number of spots. And as colleges have lost their monopoly on information, attending a better reputable school has become less about learning and more about signaling. As Caplan describes it:

Would you rather have a Princeton diploma without a Princeton education, or a Princeton education without a Princeton diploma? If you pause to answer, you must think signaling is pretty important.

Alternative methods of accreditation outside of universities through more entertaining and personalized online learning continue to become better and better. Thus, the signaling part of attending college diminishes quickly. Perell foresees Harvard and Princeton to do fine but that dark days are ahead for mid-tier-universities.

To be sure, entertaining online lectures aren’t enough to overthrow the university system. Accreditation is the final pillar holding the system together. Accreditation methods will form slowly, so the transition away from universities will be gradual.

***

I personally find the future of education a tough issue to forecast. Universities and the system operating around higher education not only evolves around the amount of information possessed and taught, but also funding scientists and fueling scientific progress, being the guardian of reason and civic idealism, etc. As we currently stand, I think online and traditional education offer their own unique advantages. Nevertheless, Ben Franklin’s vision for democratizing education for students from all social strata has gotten an enormous boost from information abundance. And one thing is certain: a democratized and easy-to-access educational system will have a tremendously positive effect on the future shape of society.

Foresight #3: Politicians will increasingly look like anti-establishment celebrities.

The world is drowning in skepticism and uncertainty, and trust in institutions is losing ground on a global basis. As a political tool, populism seems to never have been as effective as it is now.

The reason is that with the arrival of information abundance, political parties can no longer control and monopolize political messaging, and media is no longer a barrier against diverse thought and opinion.

In the era of Mass Media, voters were a means to an end of reaching political power, and in order to appeal to the masses, politicians encouraged centrism with respect to authority. To a much larger degree than today, voters found common ground in their beliefs and interests.

That media monopoly has disappeared and voters can now find, select, edit, and distribute content as never before. Meanwhile, ideological polarity has become the political norm in many countries. As Perell writes:

The Overton Window has been shattered… Extreme opinions, which were once squashed by the Mass Media environment, can survive on the internet, where a viral message can spread to every corner of the globe.

Groups that were once passive and neutered by media now start protests and demonstrations, such as the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street, and authorities are losing grip on informational control.

While fast and wide distribution of information has significant advantages, including quick uncovering of scandals, there are problematic side effects. Low production cost of information consequently lowers production filters which then gives rise to fake news and cynicism. False or damaging information spreading on social media is filtered only at distribution, not creation, and then it might be too late before the content has went viral.

Singapore recently announced a “fake news” law where the government instructs social media companies to publish a correction notice on posts that they claim to contain false information. The initiative has received global criticism as a measure to limit freedom of speech. But given how serious a problem online falsehoods are, are there better ways to grapple with this problem? That’s tough to say.

The most powerful feature of modern communication mediums that many fail to recognize is how they affect the social, economic, political, and religious patterns by which society operates. As Perell states; everything we do and think is shaped by the technologies we build and implement.

***

Reading David Perell’s essay made me think about Claude Shannon’s information theory. He recognized the utter importance of how to quantify, store, and communicate information, and without him, there would have been no internet. Not only did his information theory transform the digital communication revolution, but it also had a huge impact on probability theory and the fields of finance, investing, and gambling. Of course, Shannon later proceeded to achieve one of the best investment records in history.

What we as investors must be attentive to is to decipher what information is important and what is minutiae by being careful of what information we absorb. But mostly, how the medium of that information influences our thinking and perception of reality.

The first step is understanding how the new digital environment with information abundance changes the behavior of consumers and voters, whether its in commerce, education, or politics. Only then can we recognize how media influences ourselves and learn to absorb information on a rational basis. And only hereafter can we use this insight in aiming to predict how society might look in the more distant future.