I was originally going to do a write-up of Topicus.com, but as I got more and more into it, I realized that it wouldn’t work without writing up Constellation Software first. So I changed the write-up to Constellation and will write up one on Topicus next. (Read it here).

I recently read Michael Lewis’ book, The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story and one thing that stuck with me was his reference to the phrase “business model” as “a term of art”.

This is what Constellation is: a piece of art painted on Mark Leonard’s canvas. His annual shareholder letters (which started out as quarterly after Constellation listed in 2006, turned into an annual occurrence in 2009, and now arrives whenever Mark feels he has something to say) possess refreshing humility, a high display of competency, and a nail-to-the-head type of writing that makes understanding the business one of the easiest things in the world. In fact, many investors might even be better off reading all his letters back to 2006 to arrive at their own fair assessment of the business rather than reading my, or any other’s, explanation of it. To learn a bunch about how to straight talk, I urge you to read all his letters (find them here).

An example of his humility was on display in the 2015 to 2016 letters in which he set out to study other “high-performance conglomerates” (HPCs) such as Constellation, even as his company itself by many measures was the most successful of the rare bundle of companies you could categorize as an HPC. Over the past decade up until 2015 when Mark set out to do the study, Constellation itself had compounded revenue per share and CFO per share by 24 percent and 30 percent, respectively, with no buybacks to influence the share count. The share price had gone from $CAD 24 to $CAD 510, about 36 percent compounded over the same ten-year period.

What he found in his study was a few patterns in the HPC’s lifecycles that consisted of three main phases: In the first phase, the HPCs started out earning extraordinary returns through operations in asset-light businesses. In the second phase, they embarked on attractively-priced acquisitions to which they applied their increasingly refined operating practices learned from phase number one to increase the returns on their investments. Lastly, in the third phase, they drifted towards paying higher multiples for larger acquisitions as size became a constraint and declining ROIs across the whole conglomerate turned inevitable.

Constellation hasn’t shown reversion to the mean in any meaningful way yet but likely found itself transitioned to the third phase very recently for reasons I’ll discuss in the following.

Throughout its company history, Constellation has earned the high-performance badge largely from intelligent capital allocation in the VMS business rather than operational excellence. Not that the operations at Constellation’s VMS businesses haven’t been excellent—obviously, that goes without saying—but that’s largely been a result of earning a high return on existing capital rather than reinvesting new. And by existing capital, I mean essentially no capital.

Due to an advantageous cash conversion cycle and minuscule fixed assets, Constellation has historically been a negative-tangible-net-assets business. Goodwill and intangibles comprise the vast part of the balance sheet, but these are amortized every year, even as the economic reality of the asset acquired doesn’t lose economic value. What happens when you’ve got such a business is that ROIC can sometimes fly into the sky, and other times, as in the case of negative invested capital, into infinity. So you need another measure for the capital invested in the business. Since debt has been historically absent from the capital structure—as have buybacks—Constellation has always used share capital + retained earnings + accumulated amortization as its definition of the company’s invested capital (or how much owners have invested into the business), which makes sense since the business is capital-light and has consistently reinvested more than its FCF.

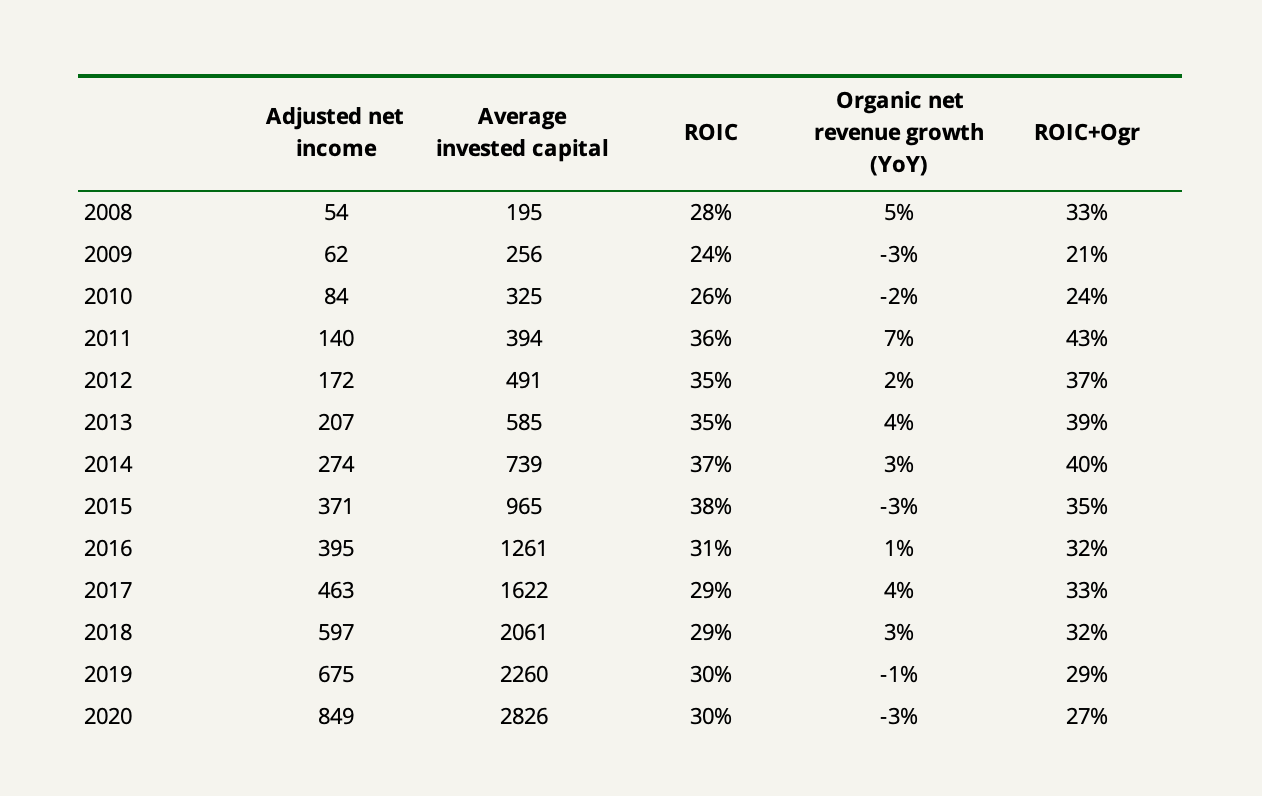

Adding the return (net income + amortization) made on this capital to organic growth has been Constellation’s historical proxy for the intrinsic value growth to shareholders. And while it has been quite remarkable, you can see the evidence of how the factor that has propelled intrinsic value forward lies in excellent capital allocation rather than organic growth:

The historical performance in ROIC+OGr shows that as consistent Constellation’s excellent returns on capital have been, equally consistent have the disappointments been in terms of organic growth. It’s not that Constellation is striving for high growth at the business unit level anyway. It used to do it, but that was until it learned some more about the nature of the business it was in. Constellation used to target annual organic growth in the 5-10% range until 2009 when the goal was adjusted down to a little above the growth in GNP—or mid-single digits.

The organic growth constraint inherent in Constellation’s VMS businesses originates from the same source that makes up their moat. Constellation’s VMSs are far from your hot software company. Where the mantra in horizontal software—AI, data storage, cybersecurity—is bigger and more powerful, the VMS mantra is smaller and iterative. Whereas horizontal software companies are trying to prove a product to a huge TAM with huge runway, VMS businesses are already proven in their own, often saturated niche. Where horizontal software companies try to create something like an entire social network, VMS businesses make something like the underlying software system of a local fire station. VMS businesses are not disruptive but they are not subject to disruption either.

You can imagine the moaty, once-monopoly-like local newspaper business that Buffett and Munger used to be into. The similarities are numerous: scarce competition, differentiation, high gross margins on incremental sales, minimal churn from high switching costs (financial for Constellation’s customers, informational for the newspaper customer).

The latter, high switching costs, come from iterative feedback loops with the VMS’s customers. To the customers, the highly customized software delivered by a Constellation VMS is usually mission-critical and a need-to-have. Constellation’s VMS businesses help their customers run their businesses efficiently, adopt their industry’s best practices, and adapt to changing times. The longer the VMS works together with the customer to fine-tune their needs, the wider the moat around the business becomes. For a new entrant to even come close to competing with that, they would have to go through a lot of trial and error themselves. But even so, the annual cost rarely exceeds 1% of the customer’s revenue so a customer wouldn’t even bother trying a new vendor unless they can provide something revolutionary to the customer’s operating efficiency. As a result, Constellation consistently retains +90% across all VMSs.

So instead of expecting a sudden magical uptick in organic growth, the more pressing question, I think, is whether Constellation’s existing portfolio of VMS businesses can continue to generate a predictable level of cash flows for decades into the future which is needed to continue running Constellation’s well-oiled M&A machine. My opinion is that this is where the similarity to the local newspaper business halts. Ironically, the one factor that crept in to disrupt the declining newspaper business was…technology. Constellation is not prone to technology disruption (at least not in any way I can imagine). Rather, it’s in a technological sweet spot as evidenced by its consistently high returns and low churn. I don’t see much of that changing. In reality, Constellation is one of the few technology businesses in which you would feel safe adding back all amortization expenses every year to adjust the net income (like the company does in its calculation of ROIC) and feel content with that since you know that the economic value of the goodwill and intangibles remain.

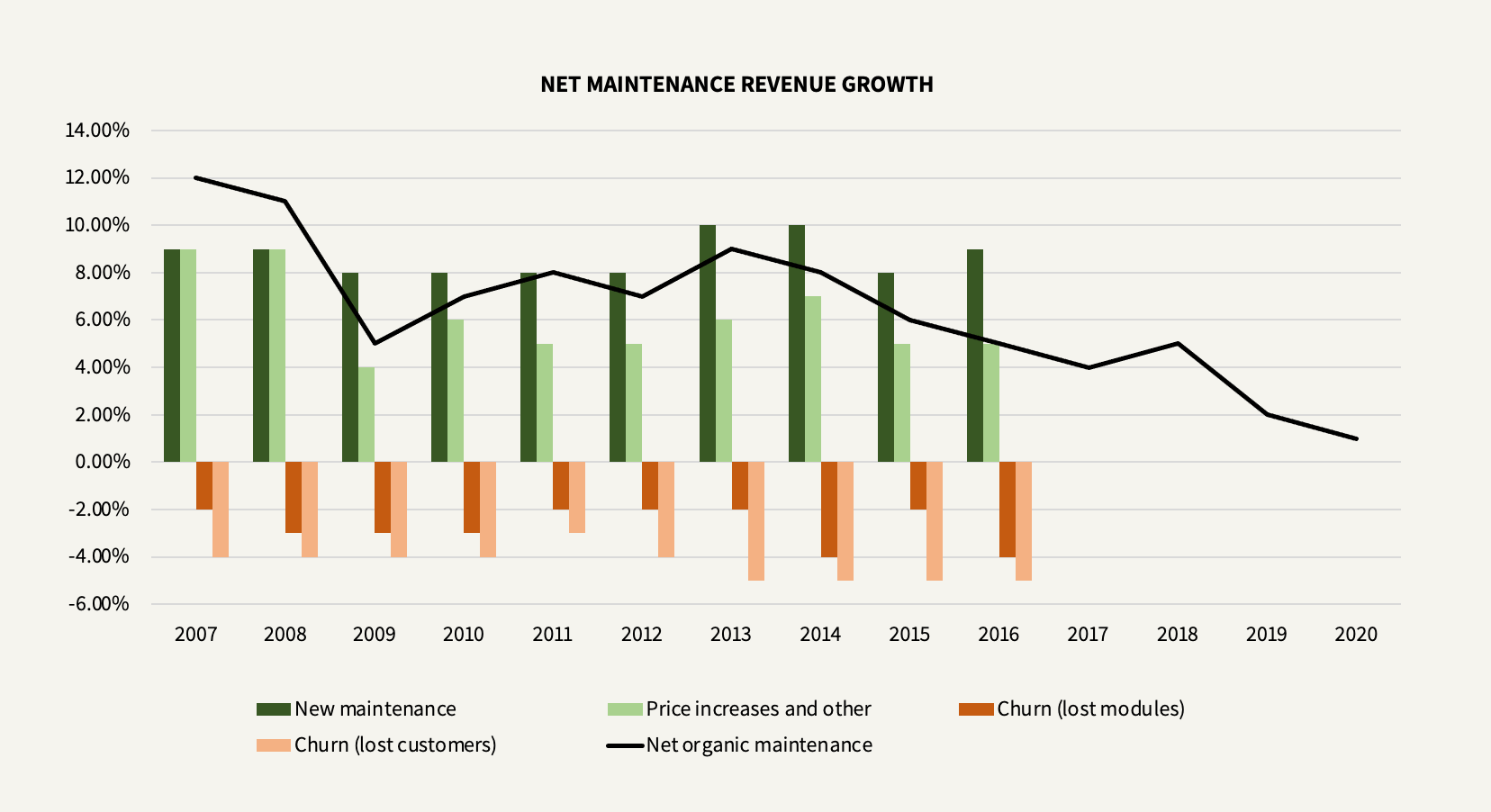

To elaborate on that last point, Mark has many times raised the importance of looking at the company’s organic maintenance revenue growth as an indication as to whether the VMS’s lose intangible value. As long as maintenance revenue (recurring revenue primarily consisting of fees charged for customer support on software products post-delivery) grows organically, you can make the case that the value of the company’s intangible assets has not declined but actually has appreciated. Up until 2016, the decomposition of maintenance was broken out into the following, but since SaaS revenue has begun to comprise an increasingly larger share of maintenance (as seen below starting in 2013), the company stopped showing the decomposition, likely due to historical incomparability (SaaS revenue involves higher churn, but it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a worse type of business).

Another point one needs to know about the VMS businesses that Constellation looks for: The flip side of many software companies’ capital-light operations is that they need to spend a commensurate amount on R&D and S&M in order to stay much in the same place. At Constellation, this doesn’t weigh to the same degree:

Our favorite businesses are those that are growing just slightly faster than their markets, gradually adding market share and customer share (i.e. “share of wallet”), while generating a good return on the capital that they have invested to produce organic growth. Small market share gains are much less likely to trigger a scorched earth competitive response that erodes pricing and triggers wildly unproductive R&D and S&M binges. We believe that we have struck that balance at many of our businesses.

Because Constellation buys stable and mature niche VMSs, the R&D spend at the business units is largely attributable to growth investments, not maintenance. Constellation can afford to slow down discretionary costs and investments when few Initiatives (significant long-term investments required to create new products, enter new markets, etc.) have commenced, increasing FCF. Which it did, after 2005, where the company found Initiatives to account for over half of total RDSM expenditures until it was rationalized and new Initiatives plummeted. What Constellation did was to keep the early burn rate of Initiatives down until it had proof of concept and market acceptance, sometimes even getting clients to pay for the early development.

These points are basically all one needs to know about the VMS businesses. The key idea is that it’s these factors that allow Constellation to pull out lots of FCF from its existing VMS portfolio on very little tangible assets which it uses to pursue growth by buying lots more VMSs. The majority of this M&A responsibility lies with the company’s six Operating Groups, each responsible for at least 200 business units in different industries operating across a wide range of competitive environments.

The business units within the Operating Groups share capabilities in accounting, acquisition, IT functions, and varying degrees of HR, tax, R&D, legal aspects, as well as senior staff who sometimes will be parachuted into large new acquisitions or troubled situations. Also within the Groups sit Portfolio Managers who are usually promoted VMS managers who have shown excellence first in operations and then in capital allocation and are now responsible for a concentrated number of business units between two and twelve. Together with another double-digit number of M&A specialists spread across the organization, these Portfolio Managers spend >50% of their time on M&A and the rest of the time advising their business units. If a really excellent Portfolio Manager proves themselves through multiple successful deals, they might be given the “Compounder” designation.

Below the Operating Groups sit the business units (BU’s) where each usually contains a single VMS but sometimes a few of them. The business units are treated exactly as the designation implies: they are separate entities. They possess full operational autonomy, are held accountable for their own results, don’t cross-sell products, and they might sometimes even compete with one another for the same customer.

The Manager (or “Craftsman”) of the BU is nearly always from the acquisition itself, having deep expertise in the vertical. Once in Constellation’s fold, the BU’s are kept deliberately small to remain agile and to prevent overhead creep (which is also a function of Mark’s experience with small high-performance teams from his time as a venture capitalist—kind of akin to the “day 1” mentality embraced by Jeff Bezos). Because the BU managers know this, they have an incentive to groom other promising functional managers beneath them who might be enthusiastic about running and growing a spun-off BU so that they themselves increase their track record as leaders and capital allocators within the organization. As the BU Manager’s ambition drives them to acquire another VMS, their role is usually changed to Player/Coach. And if things go well, and the Player/Coach finds a second or third VMS to acquire, they eventually have to give up the day-to-day responsibilities and become a full-time Portfolio Manager by moving up in the Operating Group level. Once a Portfolio Manager, the Manager’s job changes to advising aside from capital allocation. They fly around to their BU’s, gather information, share ideas and problems with other people within Constellation, fix the problems with the BU Manager, and then move on to the next portfolio company. If the new BU Manager disappoints, it’s up to the Portfolio Manager to find a replacement.

It’s very interesting because it’s here the big difference lies between Constellation Software and the biggest HPC in the world, Berkshire Hathaway. Like Berkshire, Constellation’s organizational structure is highly decentralized (out of a total of approx. 25,000 employees, only ten people sit at Headquarters in Toronto—a ratio of 1:2,500). But while Berkshire’s capital allocation responsibilities are almost solely held at Headquarters with Warren Buffett and, to a lesser extend, Todd Combs and Ted Weschler, this job is spread widely throughout Constellation’s organization.

Mark was Constellation’s first Portfolio Manager but he already ran out of capacity around mid-2005 when the company was at $200 million revenue and ran about thirty BU’s. So when he recognized that he couldn’t keep an overview of the important things going on at the BU level and that he could no longer be the primary driver of M&A, Mark began delegating the responsibility to the Operating Group Managers for monitoring and coaching their BU’s and to also assume responsibility for deploying the majority of the company’s FCF. One would think that the dilution of capital allocation responsibility would also dilute the returns, but since then, the returns on capital have only expanded. Today, each of the Operating Groups is essentially the equivalent of what Constellation was a decade ago and each Operating Group Manager is continuously delegating their monitoring, coaching, and acquisition activities down to their Portfolio Managers, expanding the organization and resuming the cycle.

Many would agree that this system very likely wouldn’t work for Berkshire. So why has it worked so well for Constellation? My opinion is that it all boils down to Constellation’s well-designed incentive system that seems to work perfectly in a niche system but may find trouble if it expands out from the niche.

First, Constellation’s incentive system pervades from the top instantiating a mentality of ownership down through the organization. Bonuses depend on two variables: ROIC and net revenue growth, striking a good balance of how responsibly the Managers deploy capital. If the Managers hold excess cash, they have an incentive to send cash to Headquarters to lower the denominator in the ROIC equation. If the Managers recklessly deploy FCF into bad Initiatives or acquisitions in an attempt to boost revenue growth, ROIC will suffer, and so will their bonuses. In fact, because ROIC is so central to the compensation, Constellation has mostly struggled with making their Managers keep their profits to keep ROIC from running too wild. Second, instilling a long-term ownership mentality throughout the organization, Operating Group managers are required to earmark 3/4 of their tax-effected bonuses to purchase the company’s stock while all employees above a certain level of compensation must also purchase a certain amount of stock and hold them for at least four years.

That Constellation can trust so many people in allocating its capital is a feat in itself. It’s only possible because every VMS acquisition is very much alike and every acquisition is pursued based on the accumulated data from Constellation’s historical acquisitions that allow capital allocation to remain rational, not emotional. What this means is that Constellation has distilled its acquisition strategy down to systematic processes which can be learned by others. In fact, almost no Manager within Constellation had done an acquisition before coming to the company.

The incentive system also creates immense organizational career opportunities. The journey from Craftsman to Compounder is, of course, very financially rewarding, but it’s also a realistic feat for any employee at the low ranks in the meritocratic system. The system works because employees mostly are willing to stick around due to a high degree of trust that their performance and KPI’s will be noticed and awarded accordingly.

(In Mark’s HPC study, he found that only one other HPC has followed a strategy of buying hundreds of small businesses and managing them autonomously. They eventually caved into increased centralization. Mark suspected the missing piece was a seamless web of trust in the system. ”If trust falters the BU’s can be choked by bureaucracy.”)

Constellation looks for two types of businesses to buy. The favorite is the one where it buys directly from the founder of the company who has spent the better part of a lifetime building the business, thereby instilling a long-term orientation throughout the enterprise. Constellation appeals to many of these founders because it offers something many other potential buyers, such as VCs, don’t: a long-term safe haven that cherishes the enterprise’s autonomy. The company also dabbles in distressed assets—for instance, a failed synergy experiment from a large corporation that has scooped up the VMS with the intention of integration only to divest it again. These kinds of acquisitions have turned out the most lucrative for Constellation at times of recessions.

For any large acquisition that the company pursues, the diligence, structuring, negotiating, and integration is led by a single Portfolio Manager, routinely a “Compounder”, who shoulders the responsibility for the process and the outcome. This Portfolio Manager and their team follow the hurdle rates set by Headquarters. This hurdle is all that matters since Constellation is agnostic about how the return on investment will arrive—IRR is what Constellation cares about, irrespective of whether it is associated with high or low organic growth. It buys shrinking businesses if it meets the hurdle (even as mixing growing and contracting businesses in one company creates many interesting cultural challenges). More often than not, non or slow-growing businesses are the only kinds the Portfolio Managers can find that meet the hurdle. Even in an environment with investors throwing themselves over all things tech, those kinds of businesses are deemed boring. Therefore, Constellation will sometimes be the only buyer in that corner of the market, and on top of that, promising a safe haven for sellers puts it in an attractive position to bid for lower prices. So akin to Berkshire, Constellation tries to avoid bidding wars, offering one price which the company can accept or not.

And now we’ve boiled down to the key problem which is the most important variable that has determined the past and will determine the future for Constellation: the price paid for acquisitions. Taking each year’s revenue growth from acquisitions and the acquisition spend to assess the average implied P/S multiple paid in the given year, one can calculate that almost every year in Constellation’s history the company has paid <1x sales for every acquisition made.

However, as mentioned at the beginning of the write-up, Constellation has likely entered the third phase of declining returns as an HPC. For just the past four quarters, the company has generated almost $1 billion in FCF, up almost 2x from just two years ago. To sustain its growth by acquisition to the same degree, in the same type of businesses it historically has acquired, and at the same multiples, Constellation would likely need to swallow north of 140 companies next year and/or pay up higher multiples for bigger whales. Yes, for the next maybe two to three years, it’s going to be hard, but doable (in the 2021 letter, Mark assured that the company will continue to invest most of its FCF in small and mid-sized VMS acquisitions at the traditional hurdle rate), but just a few years out, it’s going to become a colossal challenge to find such a huge amount of good deals at <1x sales in VMS let alone to train or find a large number of Portfolio Managers as competent as the current Operating Group Managers (Topicus.com, a large acquisition, was bought at 1.8x sales). So now the question in my mind is not if but how slowly the return will revert.

For many years, Constellation used to track large VMS acquisition prospects as a separate segment of the market. Historically, only 10% of FCF has gone to this segment with only three large VMS acquisitions undertaken throughout the company’s history (out of between 40 and 70 large VMS businesses that are sold each year). As the company becomes forced to compete in this market and move up the acquisition size ladder for VMSs, the peers become private equity funds more than anything (Constellation is essentially a public listed private equity firm itself). Competing with large VCs almost surely leads to paying up for quality and getting into the occasional bidding war. Keeping the traditional hurdle rate is going to dilute the prospects to potentially nothing, so it has to come down.

On the other hand, I don’t think Mark even cares whether Constellation invests in VMS, any other type of software, or software at all for that matter. Constellation just happened to stumble upon a multi-decade-long value opportunity in the moaty VMS business and decided to put all resources and efforts into becoming the best in that corner. But the flip side of that is that it spent all its time crafting a very narrow circle of competence and it’s not going to be easy to step outside that circle. My impression is that you will hear much more about this issue in the coming years’ reports and that Headquarters intends to do something about it on an experimental level. They might pick out a single industry with similar characteristics to VMS and spend a few years dabbling in that, seeing which investment processes already learned that fit the given industry. For investors, that’ll require lots of patience.

Meanwhile, investors will likely see returns of capital sooner than later. In his 2017 letter, Mark wrote that he would advise investors to look at the per share growth in FCF available to shareholders (FCFA2S) rather than the combined ratio of ROIC+OGr going forward as a proxy for the growth in the stock’s intrinsic value. Note that a measure like ROIC+OGr is only valuable as long as the business remains capital-light, as long as the economics of the acquisitions are similar to those in the past, and as long as the company can continue to reinvest all its FCF. So in changing it for growth in FCFA2S, he seemed to suggest either or all of the following: a) that Constellation will likely not be able to reinvest all FCF generated going forward, b) that returns will slow down so that past returns on capital mislead the expected future returns, c) that Headquarters will see buybacks as a best-case alternative to acquisitions when the hurdle is lowered and if the right prices present themselves, and/or d) that dividends might become a regular thing due to the aforementioned points.

In 2013, Constellation paid a bunch of money to a group of consultants to get some estimates on the value of Constellation. At the time, Mark found the stock fairly priced, but the most noticeable conclusion about the sensitivity was this:

Varying the organic growth assumption has a tremendous impact on the intrinsic value of a CSI share. Add in another 2.5% organic growth to the baseline assumption and you get more than double the intrinsic value. Subtract 2.5% from the baseline organic growth assumption and you lose almost half the intrinsic value of the stock. You can see why so many software company CEO’s are growth junkies.

By the time the report was made, the stock was priced at ~20x FCFA2S. It was also a time where organic growth was higher and you had little to worry about in terms of Constellation’s acquisition runway. Today, at a $CAD 48 billion market cap, where organic growth is stagnating and M&A opportunities likely look to contract, the price is trading at almost 40x TTM FCFA2S. I won’t bother doing a full valuation on the company since I can make no assumptions based on what I’ve discussed in this write-up which come close to an almost 40x FCFA2S valuation today. The only conclusion I can make is that there’s a vast capital allocation premium baked into the price—a premium which may or may not be justified depending on whether you believe either that organic growth will pick up to a significant degree (unlikely), that the company can continue vacuuming up many hundreds of small VMSs at <1x sales over the next decade (also unlikely), and/or that Constellation can expand its M&A machine outside of VMS to a significant degree (perhaps likely). My conservative nature keeps me from making such assumptions.

But I may turn out wrong about everything. Mark has always been overly-modest in his statements regarding the future of Constellation which is another display of his humility and a testament to the fact that even one of the best capital allocators in the world is subject to a probability distributional future, not sure things. However, Constellation has again and again surprised on its ability to scale a strategy of buying hundreds of small VMS businesses and managing them autonomously through a trusting culture. The most astonishing feat of it all, and the most overlooked part of the Constellation story, is how Headquarters have succeeded in distilling not only operational processes but also investment processes down to systematic steps to be used by the Operating Groups and every one of its Portfolio Managers. Perhaps this time is not different and Constellation has something else up the sleeve. At least, if you’re an investor, that’s what you pay for at the current price.