I was having lunch with some of my colleagues the other day where we discussed running my former jewelry business that I’m now a passive co-owner of. We touched on the economics, attractiveness, and difficulties of starting and running an ecommerce business.

Once we got over the nuts and bolts of what one needs to do and learn to get off the ground, one of my colleagues turned to me and asked: “What returns does such a business have?” I found myself unable to answer them on the spot because it suddenly occurred to me that I’d never given an actual thought to that question while running the business. Obviously, I knew instinctively that the returns were high. I just never sat down to do the calculation because doing so would be redundant.

Let me explain.

A new entrant in an ecommerce vertical can get up and running in a variety of ways. (I’m talking about DTC ecommerce and by returns I mean unlevered, so no debt). For instance, if you outsource manufacturing, the first thing you need to do is find a manufacturer that can supply the product you want to sell. You can either be a reseller by procuring an existing product, invent your own from scratch, or be a quasi-reseller by removing the supplier’s logo and slapping your own onto it. What you then do is set up an online storefront and start selling (which I can’t tell you how to do). You either wait for your purchased inventory to arrive at your facilities or you do it the smart way and start selling by creating a bit of hype around it and start taking pre-orders. And if you’re really smart, you’ll have negotiated hard on credit terms with your new supplier. This means that from the time your order has left your spreadsheet and arrived at the supplier, you’ll have 1-3 months of free time to recoup a chunk of the cash you’ll need to pay in the future. What else do you need? You need a computer, the technical ability to set up a storefront, and some space for your inventory. Everything else is essentially operating costs.

Now what else can you do to make your capital investment disappear? You could do dropshipping, which means you’re a distributor with float and your supplier holds the inventory risk (but you risk alienating customers with long lead times and no value chain control). The fact is, almost no matter the model you pick, if you have a well-turning product, you’re going to earn high returns on capital. And if you’re good at turning your inventory, you can operate with infinite returns. Generally, the only way your ecommerce business is going to earn low returns is if you can’t get it off the ground, meaning you can’t find any customers that want to buy what you’re trying to sell, or if you can’t get a positive return on your ad spend. Of course, that’s the case for the vast majority of entrants in the ecommerce space. But if you do get it off the ground at a positive ROAS from the get-go, the returns are going to come pretty quickly.

What I just described probably reads like the easiest business in the world. It’s certainly attractive if you sell the right product, in the right category, at the right time, and you have some technical ability, both backend, frontend, and in ad optimization. But since it is such an ‘easy’ business, the barriers to entry are non-existent. Shopify has lowered them dramatically, and a huge wave has rushed through the dropshipping sphere from hundreds of course-selling online charlatans promising everyone that dropshipping is the easiest thing in the world. Many online stores have no differentiated products in any way. The second-order effect of that is that unless all the above works heavily in your favor, competition is going to clamp down on you every time you try to scale. Creating a profitable ecommerce business is easy. Scaling it is diabolical and requires considerable luck, timing, and ability. Once you try to scale aggressively, you sacrifice your returns and the ramp is steep.

For investors, there are two lessons on returns. One is that investors tend to think growth is this magical thing that comes from returns. You reinvest 100% of your earnings back into your 20% ROE business, and voila, you grow 20%. Truth is, independent of what the spreadsheet says, customers don’t magically show up on the doorstep because you decide to reinvest in your business. They sometimes do, but other times it’s reinvestments down the drain. The growth/reinvestment equation is a chicken and egg problem because incremental returns on capital can be vastly different from historical returns. Every incremental investment made in a business is a new investment. Some businesses can keep doing what works, putting up one easy decision after the other, and others can’t. Entrepreneurs rarely think of ROIC in day-to-day operations in the sense investors do. They have their eye on a slightly different ball which are the unit economics and the incremental unit economics.

What investors also frequently misinterpret about returns is that they place an equal weighting to the importance of precision in low and high return numbers. Whether low or high, investors like to get such numbers precise because it allows them to compare between peers, the business’s past, and its cost of capital. They think the variance around a 50% return on capital should have an equally important focus as a variance around a 12% return on capital, and that a 200% return business is equally better than a 100% return business as a 20% return business is over a 10% return business. This isn’t the case.

Does that mean a 100% return on capital can be as good as a 200% return business? Yes it can… mostly, because it also depends. One of those could be dependent on float, which in turn could entirely be a function of industry nature, and the other not, making the float-independent business the ‘better’ business in terms of quality. In the first case, the business could have relatively lower margins but high turnover due to the float (which could turn against you), whereas in the second, the business may just by its nature require zero capital investment. Both returns indicate that 1) they are wonderful businesses and 2) others want to steal their pie, but they essentially tell you the same thing in either case. None of those businesses can grow at their rates of return for a long time except for perhaps the very immediate term.

The solution to all this is to reverse the chicken and egg problem so that growth not becomes a function of how much you reinvest but your cost of growth (low returns = high cost). Once you get to the kinds of returns where it wouldn’t be possible to grow at the rate for long, there’s little difference between a high and an infinite return on capital. In either case, the business can pay out 80-100% of earnings and still grow at the rate it ‘wants’. The problem is when the rate at which it wants to grow becomes severely constrained by exogenous factors, whether it be market size or industry dynamics that make it hard to scale. Everyone knows that Mastercard is an amazing business, not only because it has ridden a long cash-to-card runway and will likely continue to do so while sitting on an enviable position at the top of the payment stack, but because it can do so while requiring negligible capital investment to capture that growth and turn it into value. But Mastercard cannot grow at its >100% ROE or 40% ROIC.

Once you have a business like that—very high (or infinite) returns on capital, high FCF conversion, and high level of predictability (the hardest part)—your valuation turns easy. You take the owner earnings yield, add the annualized long-term growth you expect it to grow at, subtract a little for your margin of safety, and that’s your long-term return if you were to buy the entire business. If you only buy a chunk of it and get it below everyone else’s required rate of return, your return will be higher once everyone else realizes your growth estimate to be right because the multiple will expand.

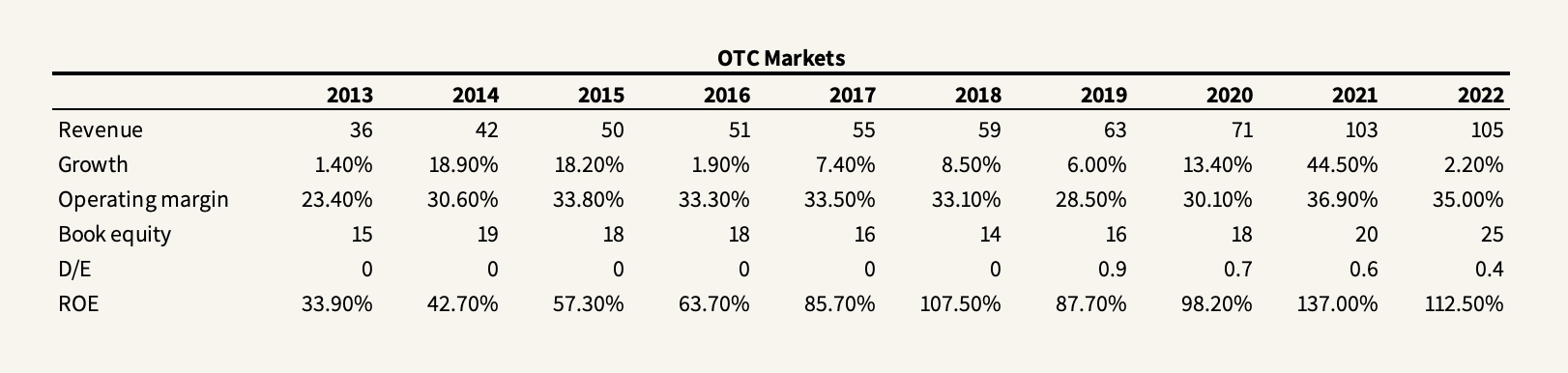

Take OTC Markets ($OTCM) for a less-known example. Over the past 10 years, OTCM has grown revenue by 11.6% per year and EPS by 17.7% per year. Meanwhile, ROE has gone from 34% to 113%. Margins have gone up on lesser incremental capital invested and ROE has increased at a rapid rate. What this means is that OTCM’s (due to float) incremental returns are far higher than 100% in those years. Its business doesn’t need capital to grow but is largely at the mercy of the growth of the overall stock market and the popularity of alternative exchange listers because the volume of issuers depends on it (hence the 2021 growth number).

All of this is also to say that growing a business is hard, unpredictable, and comes down to honing your circle of competence. If you’re an entrepreneur, the better you are at your particular craft, the better you will be at projecting growth. If you’re an investor, and you get too bogged down in a spreadsheet model, you’ll miss how difficult, sometimes impossible, the variables you’re modeling out are because you’ll miss how path-dependent your model will be which is something people always underestimate. If the path to success depends on a multiplicative formula of a string of events, you almost always land at actual low confidence levels even if those events individually have a very high (+90%) probability of going right. And once you realize that, you appreciate how hard it is to value companies. You’ll end up valuing and picking much fewer companies than you were before. You’ll try to do less.

I frequently place zero to negative value on growth guidances by management and prefer to not even hear about them. Way too many managements go through the unproductive exercise of putting out public growth expectations that render them focused on short-term results and ill-advised incentives such as pleasing the street or unlocking option value. Large, consistent growth projections are what the analysts want to hear and what the investor relations departments want the management to say because it makes their life easier. It’s the perfect setup for doctoring up future figures. For very few of the ones making those projections, you can expect them to be there 10 years from now doing the same thing. If managers were to adopt the shareholders-as-partners mindset, I reckon the number of growth guidances put out there would be cut by more than half. The best case is if management is not communicating what their expectations are but you can see the logic to what they’re doing.

Attractive returns on capital, whether current or future, help you identify wonderful businesses but it doesn’t help you with answering the growth question which is far more pressing and detrimental to the intrinsic value you’re trying to estimate. Being a math wiz doesn’t make you a better investor. Luckily, thinking as a businessman does.