As urbanization continues its ever-increasing trajectory, especially in countries with rising middle classes, it’s evident that you as an investor would want to find a “toll road” company that would take advantage of such a development. To me, elevator companies come to mind. An elevator install predictably lasts for many years, often by the same age as the building in which it’s installed. And although elevator riders do not pay a toll on every ride, the building owner does pay an indirect toll. The more an elevator is driven, the riskier it is to keep in operation, and the more maintenance, repair, and modernization are required, the more it leads to tremendous service fees to the vendor throughout the elevator’s lifetime.

What’s to like about the elevator business is that it’s simple, predictable, and earns attractive returns on capital. Interestingly, the four major elevator players globally, Otis Worldwide, Kone, Schindler, and private equity-owned TK Elevator (in addition to several smaller players in APAC), are about the same size give or take a few billion, trade around the same multiples, and share fairly similar economics. The world will always need elevators and escalators (it will need more as far as the eye can see), and given the security and trust involved with selecting a vendor, future business continuously accrues to one or each of the four major players, creating a natural oligopoly.

An elevator’s life begins at the construction of a building when one of the big fours is hired to supply and install one or more elevators. Once an installation is done, the vendor turns it over to the owner and slaps on a one or two-year service agreement that underlies the warranty of the elevator. Once that agreement expires, the owner is free to hire whoever they want to regularly maintain the elevator as mandated by law. What typically happens is that the owner, perhaps from inertia or risk adversity, decides to continue the service agreement with the vendor. After all, the vendor knows the product inside-out, is properly equipped to support the owner on any ad-hoc issues (at a price, of course), and has the spare parts to support it.

For the elevator vendor, it’s this latter stage, the service stage, that’s the good stuff—the bucket of gold waiting at the end of the rainbow. The installation itself is the riskier, more cyclical phase since it follows the cynical construction cycle which in turn follows the debt cycle, is subject to labor and raw materials price swings in the construction process, and competitors bid aggressively to get their elevator inside the door. So selling an elevator is in itself a mediocre high-teens gross margin business but vendors are willing to jump through these hoops for the lucrative mid-30s to mid-40s gross margin service agreements (maintenance, repairs, and modernizations) that await once the job is done.

Because elevator maintenance is mandated by law, the work is dependable no matter the economic backdrop. And because these service agreements are sticky due to the reasons mentioned above, the durations, sporting >90% retention rates for the big fours, are very long. An elevator is retired only once a building is pulled down or during an (infrequent) major conversion so it can serve for up to 30 years. And since the service market isn’t just dependent on new elevator installs but can also be managed by increasing conversion from new installations, improving retention, and recapturing off-portfolio units (those elevators that are installed by a vendor but are maintained by a third party), the result is that the service market continues to grow by mid-single digits year after year. During 2006-09, stable growth in the service market was the primary reason why the elevator business remained broadly stable.

The customer who picks a service vendor is generally different from the one who initially makes the installation decision so not every new installation ends up on the elevator vendor’s maintenance base. The general rule of thumb is that 2/3 of elevators installed convert to a service agreement once the initial service period wears out but conversion rates vary significantly from 1) developed to developing countries and 2) by the scale of the project. For example, China, the world’s now biggest elevator market accounting for 40% of the global installed base, has notoriously been a hard market for service conversion with an industry average of ~25% throughout the country’s construction boom. For comparison, conversions are >80% in Europe. Also, a major part of China’s construction boom has been in residential real estate whereas the really high >60% conversion is more often found in commercial real estate and skyscrapers. For smaller installations (eg. seven-story residentials) rolling contracts usually go runs for one or two years whereas for larger installations (think hotels or airports) they may run for five to seven years at a time, implying a measly 1-2% annual attrition from an >90% retention rate.

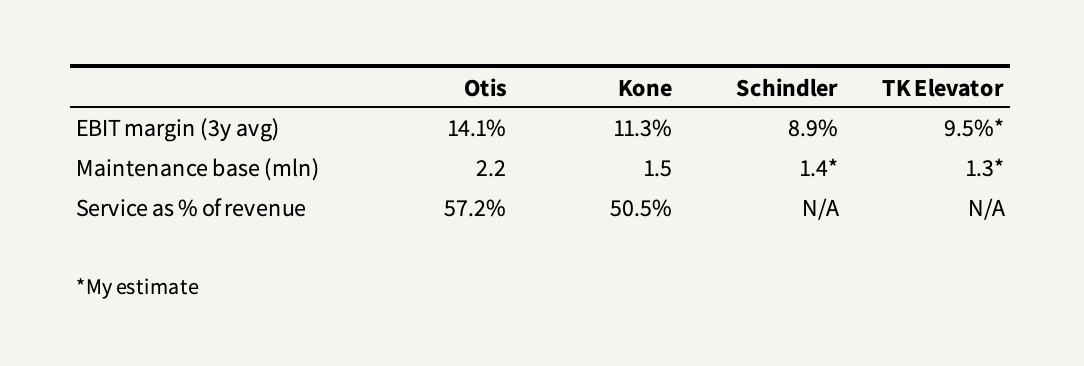

Economics of density explains why new entrants face insurmountable barriers against the oligopoly. Servicing an elevator requires extensive training and local mechanics have little incentive to become experts in an elevator that does not already have a large installed base, let alone carry an inventory of spare parts for it. Price matters little in this equation because safety is more important than the product for the customer too. There’s also leverage to geographical density. ~70% of the cost structure of an elevator’s maintenance business consists of field costs and of those field costs, ~40% can be split into unplanned callouts, indirect time spent, and travel time. A larger installed base equaling greater density and lower proximity between service work is an advantage that’s tough to compete with and which almost entirely explains Otis’s margin advantage of being the market leader with the significantly largest maintenance base:

Other than that, there aren’t really other significant scale advantages inherent in the elevator business. Being labor-intensive, high variable costs limit margin fluctuations but also limit operating leverage. Wage inflation is of little risk since multi-year service contracts typically include inflation-pegged price increases whereas one-year contracts are renegotiated annually. But while elevator vendors can pass on inflation, they can’t price much above competition and expect to retain volume.

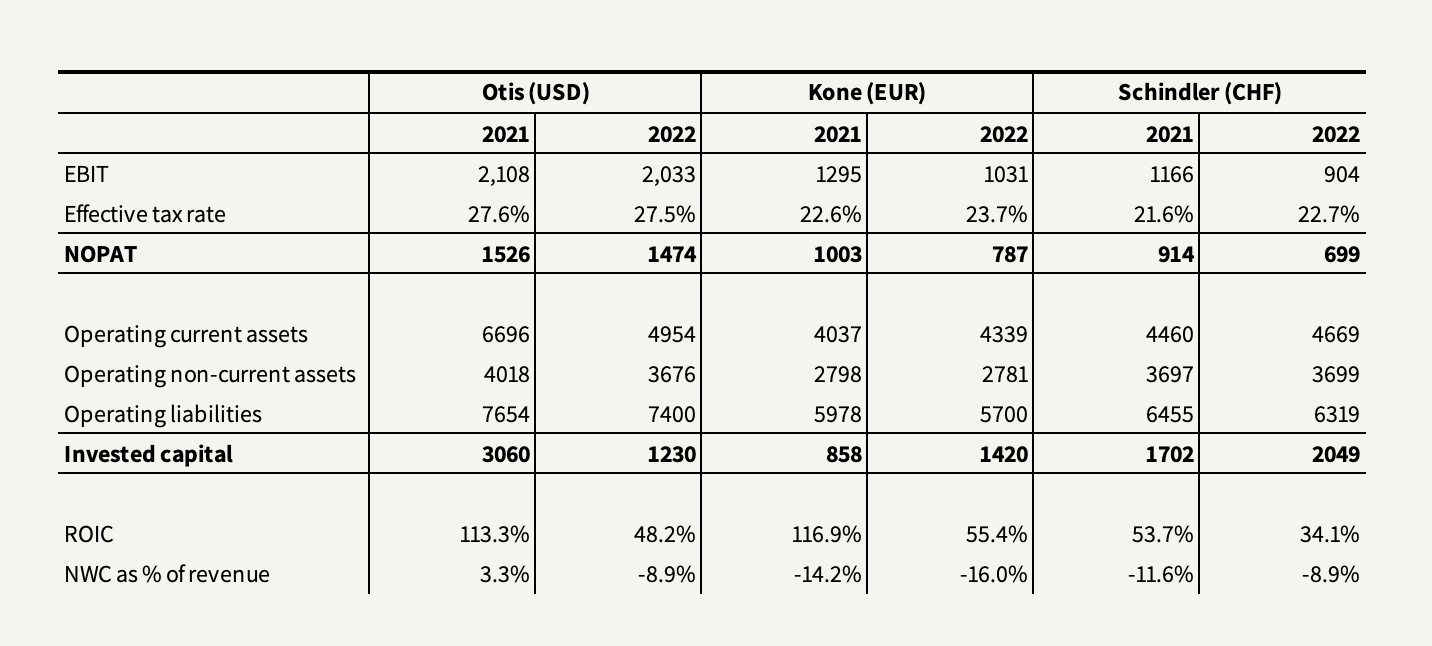

On the production side, there’s little scale advantage too. Elevator production is highly outsourced with generally a quarter of production remaining in-house (Kone states they only manufacture the components that they consider core Kone technology). However, this is also what allows elevator companies to earn sky-high returns on capital. Because production costs are largely attributed to assembly, capacity can easily be adjusted so there’s no urgency for the players to build stock or destock, resisting over/under capacity and wild price swings to the detriment of the whole industry. In fact, despite the complexity of the product and the idiosyncrasy of an installation, elevator production is so lean that when placing an order, the customer typically pays in advance for design and contract engineering followed by periodic progress payments throughout the installation. Maintenance, ad hoc repairs, and modernizations are paid in advance too. Between Otis, Kone, and Schindler they have $7.5bln sitting in advanced payments and deferred revenue, comprising ~9.5% of their collective market caps. These prepayments act as interest-free “float” that allow the companies to convert >100% of net income to cash from operations (ex-SBC) year after year.

Despite all these wonderful features, each player is constrained by the growth of the $80bln elevator and escalator industry that is steadily growing at 4-5% between new installations, maintenance, and modernization so almost all FCF goes to debt, dividends, and buybacks while growth investments—net capex + acquisitions + R&D—collectively comprise a measly 1-2% of revenues. Between Otis, Kone, and Schindler, invested capital turns over an average of 9 times per year. With little opportunity for significant reinvestment, you, depending on the price you pay for the stock, likely won’t find your growth compounder here but you can find a pretty safe, bond-like, high-yield investment.

That is, of course, unless a competitor can break away from the pack and grab market share.

For the past 20 or so years, Finnish Kone has grown slightly faster than its peers (~7.6% CAGR turning an 8% market share into 14%) first by expanding aggressively into China in 1997 despite it being a maverick market with fragmented local competition and no service market or law to enforce regular maintenance. Kone’s reach for first-mover position coincided with China getting an appetite for more, higher, and faster elevators like nothing seen since the 1920s New York City. In 2000, some 40,000 elevators were installed in the country. Last year, the number was almost 700,000 and accounted for an astounding 2/3 of every elevator installed globally during the year. And not only did China want a lot of skyscrapers; it wanted the tallest ones. Of the 211 buildings in the world that are over 300 meters, 107 of them are now in China.

(Otis really came first to China in the 1980s but wasn’t as aggressive on strategic partnerships and localized operations. And it was blamed and fined for a deadly accident on a subway that killed a 13-year-old boy and injured 30 others in 2011. But the most important reason why it was overhauled by Kone in the country was the fact that Otis was owned by United Technologies, a diverse and complex defense company, from 1975 to 2020 until it was finally spun off in a public listing in 2020.)

Of course, not all of Kone’s growth over two decades can be attributed to being early in China. After all, service revenue comprises 50% of the total and China itself is only 31%. So there’s another factor at play.

The other factor at play was Kone’s early breakthrough innovation of the industry-standard hoist motor. Before Kone introduced its EcoDisc in 1995 with its infinitely variable speed that ran on standard AC power and turned at a modest 0-150rpm, most AC-power hoist motors used cheap induction motors running at fixed speeds, typically at 1,500rpm at one level and 500 at another, requiring a gearbox and a flywheel to get an elevator moving. In this outdated two-speed elevator, passengers experienced discomfort due to rough acceleration and slow shifting between the two levels. The vast power usage wasn’t uncommon for the elevator to strain the electrical system of the building, sometimes causing all the lights to dim every time the elevator was used. The only alternative to the two-level AC hoist was a very expensive but gearless DC hoist that required a hot AC/DC converter that couldn’t fit in the elevator shaft. Kone’s EcoDisc was only 25cm wide and required neither gearbox, flywheel, or converter. It eliminated the need for a machine room and, suitable to the name, it could generate electricity when the elevator was running up empty or down fully loaded. Because it required neither of the aforementioned, it was easy and much cheaper to install in new and existing buildings, let alone maintain. Its variable speed not only made it more comfortable to ride but also reduced the tear on the machine and its ropes. Its small size and ease meant that it quickly entrenched the market for low and mid-rise residential buildings, replacing legacy hoists and hydraulic lifts, most notably across Europe where roofscapes were low and even. Of course, Otis, Schindler, and Thyssen (prior owner of TK Elevator) followed suit with their own versions but Kone’s single technology makes its installed base more homogenous to maintain contrary to other incumbents’ ‘technological debt’ within their installed base.

But Kone wasn’t just going for low-rise residential. Skyscrapers pose unique problems. Burj Khalifa has 163 floors and reaches 830m high but to get to the top, you must switch elevator at a sky lobby since the building’s 57 elevators can only offer a maximum ride of 504m due to the weight limit of the steel lift cable. Any longer and it gets so heavy that it might snap under its own weight. Because steel topes account for up to 3/4 of the moving mass of the machine it also means that taller elevators are more expensive to run. In 2013, Kone revolutionized the industry once again with UltraRope which, apparently, took a decade to develop at its laboratory in Lohja. UltraRope is a carbon-fiber replacement for steel rope that reduces the weight of the ropes by around 90%. When Jeddah Tower, the first 1km building finally opens in Saudi Arabia, it will feature a 660-meter elevator made possible by Kone’s UltraRope. And UltraRope has the added advantage that it mitigates the sway that tall buildings experience at the top because it has a higher resonant frequency. It’s also safer. Lighter ropes make braking an elevator easier should something go wrong.

It’s still some way from Otis, though. Where Kone is market leader in China, Otis is market leader in the world. Otis is the OG. While hoisting equipment in some form or another has existed for millennia (the Colosseum in Rome had 24 lifts powered by slaves), it wasn’t until 1854 when Elisha Graves Otis demonstrated that lifts could be made safe that people began to trust their lives to cages on ropes. Elisha Otis stood on a platform in front of an audience to demonstrate his invention. When he cut the platform’s bearing cable, the spring flattened and jammed into notches on the guide rails, preventing the lift from crashing to the ground. Otis as a company has existed ever since. While the company is market leader and has an iron-strong cushion in a huge maintenance base, the company actually used to be a better business than it is today. It was, as mentioned, buried in the United Technologies complex from 1975-2020. I’ve read and heard different arguments as to how the spin-off should unlock value and margin expansion because it was a neglected asset under UT which certainly makes sense when you consider the company’s plans for China. However, what’s interesting is that the company’s 10-year average EBIT margin under United Technologies actually compares favorably to today.

Where Kone’s advantage is its homogeneity, Otis’s is its adaptability. Many elevator installations require lots of discretionary work. If you have a 40-story building that requires, say, six of its elevators to have 12 rear openings along with the front openings, Otis’s production and engineering capabilities can adapt to that where it might be an engineering nightmare to overcome for the others. The more complex the job, the larger the competitive advantage Otis has. All this legacy work and proven expertise for one and a half centuries have built Otis’s reputational goodwill that allows it to hold an >17% market share. It’s also this very legacy work that underlies the company’s current 2.2mln units maintenance base, almost 10% of the global installed base, which in turn is the sole reason behind the company’s still industry-leading margins.

The advantage that Otis has in discretionary work is essentially what Schindler has in the elevator’s sister: the escalator. While having a leading market position in infrastructure and larger commercial constructions (e.g. airports and shopping centers), Schindler has made an effort to try and catch up to Kone and Otis in China, including buying Chinese elevator maker Volkslift Elevator and expanding China revenues from 12% to 16% of total revenue. Essentially a family-run business by Swiss standards, the company prides itself in tradition, although such tradition may mean it moves slower. In conjunction with its catch-up efforts, the company has undergone some operational hiccups, expensive expansion, and delayed restructurings that have hurt operating margins, currently at <10%. Still, it generates more business than Kone. Schindler is an example of the fact that you don’t need a whole lot of breakthroughs in this industry in order to keep your market position. All you need is a healthy amount of reputational goodwill and long-lasting customer relationships. Schindler may not earn Otis-level margins, but it earns enough to run a cash flow-generative business and healthy returns on capital that grow with the market.

On the growth and margin side, TK Elevator has historically shared similar economics to Schindler, growing slowly and earning slightly sub-par margins compared to the two others. And like Otis was umbrellaed under United Technologies, TK Elevator was once an asset in the German ThyssenKrupp conglomerate. It was spun off in 2020 as the tail end of ThyssenKrupp’s large restructuring program after years of dwindling profits and strategic missteps. It’s currently the fourth-largest player in elevators with a strong market position in the Americas. ThyssenKrupp retained 10% ownership and the rest is split between private equity groups Advent International and Cinven who bought at a €17.2bln valuation (17x EBITDA)—Europe’s largest private equity buyout since 2007 when KKR bought Alliance Boots. Kone first wanted to buy it with CVC Capital Partners but was turned down by antitrust concerns.

Where the Otis spin-off did little to the organization, it sparked a reincarnation for TK Elevator. It now looks to be the most innovative of the bunch—even more so than Kone. From the perspective of an elevator rider, little has actually changed over the last 160 years other than looks and comfort. You walk in, press a button, avoid talking to the people standing next to you, and you go up or down. TK Elevator may change how the world thinks about and use elevators altogether. After the spin-off, the company announced its invention of the first rope-free elevator built on ThyssenKrupp’s high-speed rail technology. They named it MULTI and it was so innovative that regulators weren’t sure whether to consider it an elevator or a train. In the MULTI system, the elevator is held in place and accelerated by electromagnetic forces, like those used for magnetic-levitation trains, which takes away all limits on height. Most importantly, the elevator can move laterally as well as horizontally, making the whole system much more like a railway which opens up a whole lot of opportunities. For example, elevator shafts can fork and rejoin to allow overtaking while descending elevators can sidestep ascending ones. The number of elevators in the system can be energy-efficiently changed on the fly to reflect usage patterns. Lastly, because elevators freed from cables have no central core, buildings could change shape as well as size, and lateral elevators make it possible to link up whole clusters of buildings. MULTI is obviously the more expensive (yet energy-efficient) option and has yet to hit the market. And while this is obviously some next-era stuff, it’s far away before it will gain a real chunk of the total installed base. The Kone/Otis story is an exemplification of how viscous market shares are in this oligopoly even as Kone owned the better technology for years and years. Capturing 50% of new unit installations will ‘only’ accumulate to ~15 percent share of the installed base over a decade. It’s also unlikely that TK Elevator will be able to push MULTI in a big way (or any way) through modernizations of what I estimate to be a 1.3mln maintenance base of which maybe 30% is entering the modernization phase. It’s not a bit easy to change a building and there’s no incentive to switch a working system to a more expensive one when you can’t even use it for its awesome features of traveling laterally or into the sky.

So, TK Elevator is ready to fight fiercely in new installations and has set Asia’s market as its target. According to this former Schindler Regional Manager, the company is willing to break the industry’s rational competition and build its maintenance base on lower margin. It currently earns the lowest operating margin of the big four. He notes they may do so because the owners try to aggressively build scale to flip it to public markets in a few years, which, granted, is the nature of PE, but I suspect such price cuts may be a structural trend.

And this brings us to address the elephant in the elevator which is the risk that vendors over-earn on maintenance through extortive pricing. Historically, maintenance contracts have been vague and don’t specify the minimum number of visits and specific tasks a vendor needs to do to fulfill the agreement. But people hate getting stuck in elevators so they agree to these contracts, paying $3-$4K/year to keep one running smoothly even as the elevator may only need a quick look-over and a dollop of grease every few months. And even if they wouldn’t mind getting stuck and wanted to fix it after the fact, the law forces them to sign these contracts anyway. No wonder this is a fabulous, protected, high-margin business.

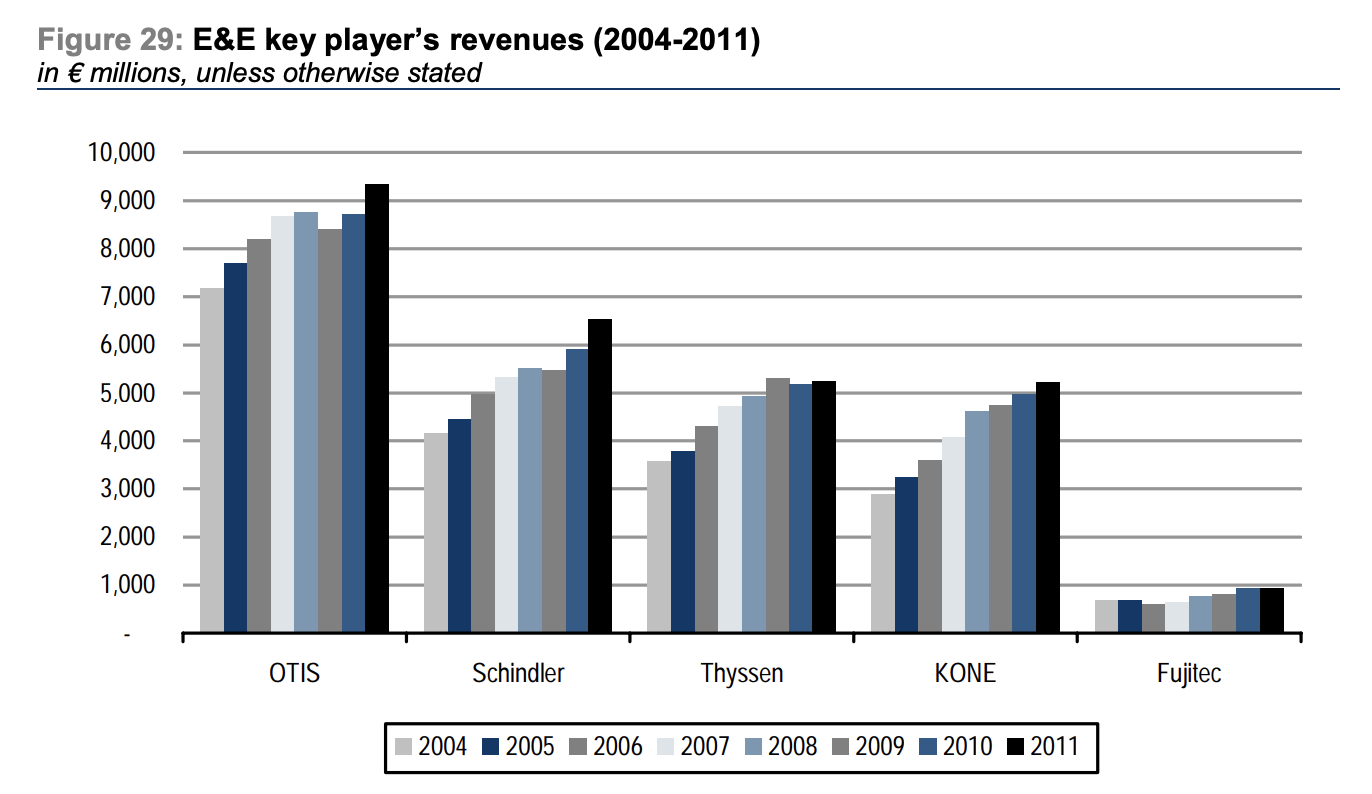

When you suspect extortive pricing, it makes sense to first go back in time and figure out how sustainable it is. Turns out all of the big four together with Mitsubishi Elevator were subject to a large horizontal price-fixing scandal in Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands in 2007. The EU Commission raided their headquarters in 2004 after receiving an anonymous tip and found evidence showing that cartel members met regularly from 1995-2004 in bars and restaurants or in secret locations where they rigged their bids and shared the markets. They were fined a collective €992 million at a time when Kone, Schindler, and Thyssen all earned <10% operating margins, a couple of points lower than they earn today.

It’s also indicative that while elevator installation is dominated by the big four, they ‘only’ hold an aggregate 50% of the units in the service market while the other 50% are serviced by independent service providers. Granted, claiming that the big four has ‘lost’ 50% of the aftermarket is kind of misleading since these ISPs account for a much smaller percentage of the value due to the type of units and level of maintenance they serve. The biggest property owners almost exclusively go for the big four. ISPs are typically run by former big four employees that undercut maintenance prices to gain incremental share but fail to gain scale while routinely being bought out by the big four. So for the big four, it’s always a back-and-forth of losing local business and buying it back and it’s always been a challenge to recapture these off-portfolio units. Otis has 2mln off-portfolio units in the global installed base and in 2021 the company announced an ambitious initiative called “Bring it Home” to recapture those.

All this is saying to me that the current maintenance prices are going to come down, although that may be over the long term and may happen slowly. Contrastingly, there are two trends that work forcefully in the big four’s favor:

1) Despite the difficulty in converting new installations to service contracts, China is not a bad market. What has happened is that the service market has lagged behind the explosion of new installations over the past decade. New installations have been so substantial that you have a different proportion than the rest of the world. The service market works like a glacier, building up over time, and moving at a much different pace than the new installation market.

But, of course, there are issues other than a fast-growing new installations market that factor into China’s tough service market. In the past, property owners and operators had little incentive to choose high-quality service providers for the peculiar reason that the property owner was not held responsible for imminent elevator accidents. And so because of that moral hazard, the owners instead went with low-cost third parties sparking a price competition that resulted in a deterioration of quality and a much more fragmented service market than in the rest of the world. Some of the property owners even chose to maintain the unit themselves. (Studies have shown that over half of elevator accidents have been due to insufficient maintenance.)

But Chinese law has changed/is changing. One of the most important changes is that now, elevator installation, repair, and modernization must be carried out by the OEMs or by entities commissioned by the OEM, which wasn’t required by the old law. Yet, the law is up for interpretation since it doesn’t specifically use the word ‘maintenance’. Third-party service providers can still carry out maintenance but cannot do new installations, modernization, and repair. But vitally, new regulations also specify that property owners will be held responsible for their safety, requiring regular maintenance just like the rest of the world. Failure to do so can result in fines up to RMB300k (~$44k). Although it’s still not mandatory to pick an OEM, these new incentives will likely push them in that direction because maintenance and repair are difficult to separate from each other. It should be noted, though, that this ‘Law on Safety of Special Equity’ was actually effective from 2014 and for the first years (until recently) it wasn’t fully enforced because developers and property owners had prioritized other problems such as being on a verge of a debt crisis which has now turned into a liquidity crisis (Kone expects up to a 10% decline in new installations in 2023).

2) Elevator companies have a solution. One thing that sets China apart from Europe or the Americas is that the density of floors tends to be higher, meaning that there are many more people per square meter. So there’s this carrot that the big four can use which smaller, local competition like Chinese Canny Elevator and Guangzhou Guangri Elevator probably cannot. When you deal with density, your solution is better dispatching. A study at the University of Illinois found that after 28 seconds of waiting for an elevator, passengers start to get irritated. Inefficiency also takes up more floor space in a building since it needs more of them to reduce wait time. More floor space taken up by elevators equals less potential rent. And the taller the building, the more efficiency matters to the owner because in the tallest buildings, which are often tapered to reduce wind effects, elevator shafts may take up 40% of the floor space.

Each of the big four has developed its own solution of making elevators smarter using algorithms and real-time telemetry that connects units, allows for better ‘destination control’ by anticipating traffic demand, and makes maintenance and repair a whole lot more efficient. Otis equips its installed units with its Otis ONE digital platform that turns them into a network of sensors, and in its latest Gen360 elevator, 360-degree cameras in the hoistway allow technicians to visually confirm, fine-tune, diagnose, and solve many issues remotely without stopping the elevator. Otis One will soon be installed in 2/3 of the company’s maintenance base.

Kone has a similar platform called KONE 24/7. Schindler’s ambition reaches wider than pure elevator maintenance. With its BuilldingMinds platform, it wants to enable property owners to use data for all aspects of managing day-to-day property operations. Within three years of inception, BuildingMinds already covers over 15k buildings worldwide. From what I’ve read and heard, TK Elevator’s MAX system is the most advanced of them all.

The ripple effects these IoT platforms create in the service market must not be understated. Preventive work and gains in productivity will overtake out-of-hours callouts, resulting in higher uptime and reducing the costly trips that are eating margins. Making a building owner dependent on a certain system to carry out maintenance increases stickiness. Otis claims that since introducing Otis ONE, retention has risen to 4-5 percentage points while service conversions in China have gone up to almost 50%. A small ISP that services, say, 10-15 elevators cannot compete with that and will be bought up one at a time.

To sum up, the golden service market is ripe for two contrasting changes: One is that elevator companies are currently over-earning on maintenance which isn’t sustainable so that’s going to come down over time and this applies to all markets. It will however be mitigated by service unit growth as vendors increasingly roll out IoT, which may help protect margins as prices come down, while surfing increased regulation in their favor in the biggest market, China. Overall, I would expect the service market to outgrow new installations for 5-10 years led by a mix of organic growth and a healthy dose of ISP acquisitions.

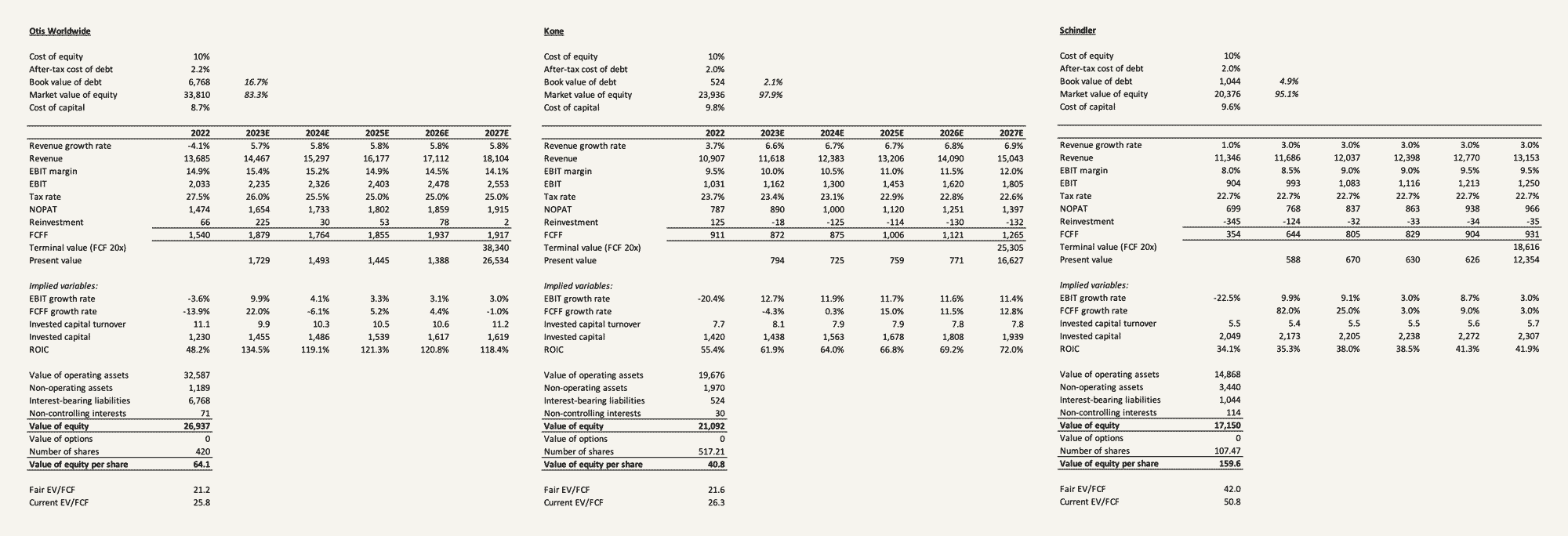

With no need to bore you more with each of their intricacies, here’s how I value Otis, Kone, and Schindler (you can download my models at the end of the write up to change assumptions):

Here’s the simpler verdict: I mentioned earlier how elevator companies can be perceived as pretty safe, high-yielding perpetual bonds. When looking at stocks with bond-like characteristics and stable free cash flows, you can safely invert the price/FCFE (i.e. after debt payments) to get the yield and then add the stable growth rate you expect those cash flows to add over the long term with the caveat that this growth has to be truly perpetual—never slowing down or turning negative. Given that the installed base is likely to be ever-growing if you smooth out cyclicality (as China matures the cycle continues in India) and this base is likely to accrue to the big four as far as the eye can see, it’s not an unfair assessment to apply to elevator companies. Otis, Kone, and Schindler all trade above the 20x range ± a few points—a <5% yield growing at 3-8% with the higher more likely in the near term and the lower more likely in the long term. Add a little margin expansion and call it an optimistic 4-5% perpetual so a 9-10% expected rate of return.

Gun to the head, I’d probably put my money on Kone, frankly because, well, TK Elevator is not publicly listed, and I like Kone’s operating and engineering acumen with no legacy “operating” debt that would be worth more than Otis’s large maintenance base if Kone could ever get its own base up to those numbers. It’s a better setup for the future of elevators and the best option for excess returns. But I don’t plan to own any of them at these prices. There’s this recurring stock market theme where what is deemed safety, quality, etc is bid up to the point where their risklessness turns out a wash in expected return. Their predictability is what provides their risklessness so that doesn’t take anything away from the fact that elevator companies are wonderful businesses and the expected return may be pretty safe. I live for predictable businesses but if I was to buy a bond, I want to do it at a bigger discount. If you’re a hedge fund managing billions, however, there are much worse places to place your capital.