Once in a while, you get to dabble in a business in which you can’t possibly have a complete overview of all moving parts but must look at the business in its entirety to keep your analysis grounded. Berkshire Hathaway is such a business. Alphabet is such a business. Alibaba is such a business.

With Alibaba, we deal with a sprawling octopus with its arms everywhere in Chinese digital society. There’s little chance for you to live in China without being touched by Alibaba, even if you live in the country’s most rural areas.

That said, I’ll now attempt to dive deep into Jack Ma’s legacy. We’ll look at the company’s history; We’ll look at each arm of the octopus and get a feel for the vision of the company’s innovation and investment initiatives; We’ll assess how resiliently the synergies between these arms contribute to Alibaba’s moat. But most importantly, facing current crackdown risks toward the Chinese tech and education sector, we’ll invert the problem and look at how Alibaba could fail with the strong possibility that things could get worse before they get better.

Lastly, as always, I’ll value the company and give a small remark on position sizing.

What Happened Lately

Lately isn’t really the right word. What’s going on in China right now started years ago. But it’s just now that things have escalated to a real panic and sell-out of Chinese equities.

If you are already aware of the current affairs going on in China and between China and the U.S., feel free to skip ahead to the next section.

Things began with the U.S.-China trade war and the 2016 presidential election. The trade war really took off on July 6, 2018, when the US imposed a 25 percent tariff on $34 billion worth of Chinese imports, marking the first in a series of tariffs imposed during 2018 and 2019. It sparked a sequence of distrust back and forth. And most critically, it sparked a race—which Europe has tried hard to participate in—in terms of who could the greatest “national champions” in the form of companies that could compete on the world stage.

To be fair, the trade war(s) have brought in several other factors other than trade that have pushed the U.S. and other countries to take a harsh stance against China, including the South China Sea dispute, the repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, the China-Taiwan divide, and the unfair treatment of Hong Kong. On June 14th, China was declared a “global security challenge” by NATO, and on June 23rd, the U.S. banned solar panel imports from Xinjiang. Then on July 9th, the U.S. added 23 Chinese companies to its economic blacklist, and finally, on July 14th, the Senate passed a bill to ban all products from Xinjiang.

In one way or the other, China’s actions, be it social or geopolitical, are all guided by the same purpose of achieving dominance and portraying the Marxist-Leninist party as an effective governing force for the present century that is able to handle a huge country of 1.4 billion people. What’s important to know is that, ultimately, this is all tied to economics. The economics has to work. Otherwise, the CCP won’t pull it off.

And Xi is well aware of the fact. In July, he reminded the state that economic work must be our core task. If we succeed in that, then the rest of our tasks become easy.

But then the question is what kind of economics the CCP wants to push China forward. In a lot of ways, it’s the same kind of economics that the West is trying to instill to deal with dominating tech business through anti-monopoly measures and masses of fintech innovations that bypass the traditional financial system. The difference is just that China seems to be much more aggressive and controlling in doing so.

Jack Ma used to be thought untouchable—that is, right until he held a speech in October 2020 at the Bund Summit in Shanghai speaking against the CCP’s way of keeping control of China’s sprawling financial sector. (Here’s a great translation of the speech). Basically, he accused regulators of stifling innovation and being out of touch. At least that’s how authorities heard it. Soon after, Jack Ma was brought in by Chinese authorities for questioning, and the next day, the $37 billion IPO of Ant Financial—which should have been the world’s biggest—was suddenly put on ice despite having previously given green light. Ant Financial was subsequently ordered to transition all of its business, including Alipay, into a financial holding company and Jack Ma disappeared for a while. Alibaba owns 33% of Ant Financial (which is now Ant Group).

Meanwhile, the Chinese government recently launched their digital yuan, the e-CNY, which might post challenges to Alibaba’s (or Ant’s) payment networks. It shows another attempt from the CCP to regain control of the financial system. The e-CNY is estimated to capture 9% of the market as a redundancy for the retail payment system, and as another slap on the wrist, the CCP has made it clear that currency could not be linked to Alipay.

But it isn’t the only time Alibaba has come under the limelight. China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) was founded in March 2018 in an effort to strengthen the CCP’s anti-monopoly enforcement. In December last year, that administration launched an antitrust probe into Alibaba for abusing its dominant market position by urging merchants to only choose one platform. A “pick one from two” practice, they called it. The probe led to a record-breaking fine of $2.75 billion.

But these events aren’t the only ones that have sparked the recent panic in the quotations of Chinese equities.

On June 30th, ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing went public in New York. The timing wasn’t great. Because few weeks before listing, China’s cybersecurity watchdog, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) began questioning the security of Didi’s network and the sensitivity of information displayed on the company’s mapping function. The CAC asked Didi to delay its listing, but despite the vague warning, Didi decided to press forward with the IPO. The IPO raised $4.4 in a lucrative market environment and it became the largest overseas listing of a Chinese company since Alibaba.

Of course, that didn’t land well with the CAC. A few days before the opening bell, the administration announced an investigation into Didi on suspicion that the company had violated data privacy and national security laws. Didi was barred from registering new users and all Chinese app stores were instructed to remove Didi’s app. The incident prompted other Chinese tech giants to look inward to not get scrutinized for any lurking data issues. Tencent halted new user registrations for WeChat citing “security technical updates”.

Social issues in China also fueled the country’s recent regulatory crackdown. Alongside national security and data privacy, China has an increasing incentive to reduce the growing wealth gap in the economy. Ostensibly, a big part of that issue lies with how online businesses have monetized essential services such as private education. Since New Oriental Education’s US IPO in 2006, The Chinese private education sector has grown into a $100 billion industry at the cost of millions of Chinese parents who plows their life savings into private online tutors in hope of enabling their children to a brighter future.

It’s no secret to anyone that China’s educational system is stressful. The suicide rate among students is elevated. The system has helped fuel a hyper-competitive societal obsession with academic achievement, through reckless pricing and aggressive advertising, to offer around-the-clock, mind-numbing tutoring. The Chinese government sees this as a potential demographic crisis and has forced all after-school tutoring companies to register as non-profits while banning classes on weekends and holidays. The entire business fundamentals of New Oriental Education and TAL Education were gone in one fell swoop as evident by their share prices. And with the CCP’s strong criticism of the monetization of essential services by the private sector, there are now concerns that the next industry in line will be healthcare.

The question now is how much further regulatory crackdowns could go, whether they are necessary or not, and whether they are fair or not. The question is also who will be next in line.

Now, this write-up is about Alibaba so we’ll dive more into the future implications to Alibaba from all of this later in the write-up. It’s a difficult thing to gauge the future without understanding the past. Let’s first take a step back and look at the company’s history.

A Good Company for 102 Years

Before founding Alibaba, Jack Ma, a former English school teacher from Hangzhou, couldn’t write a line of code nor was he a good salesman. After graduating from Hangzhou Normal University in 1988, Ma applied for 30 different odd jobs and was rejected by every one of them. In a Charlie Rose interview, he once said, “I even went to KFC when it came to my city. Twenty-four people went for the job. Twenty-three were accepted. I was the only guy rejected.” In the meantime, China was in its first decade of Deng Xiaoping’s Chinese economic reform and the economy was taking off. It shouldn’t have been that tough to land a job.

But despite not being able to sell himself to the job market, Jack Ma had a fearsome work ethic. He decided to travel to the U.S. to pursue his dream study at Harvard University. However, that dream was quickly switched out when he discovered the internet and found an absence of websites about China.

Shortly after, Jack Ma started a website with help from U.S. friends that focused on China commerce. Shortly after, he was approached by Chinese investors who shared Ma’s vision for a Far East-based e-commerce company. He opened another company called China Pages, and business was in abundance. After three years, China Pages was valued at $1 million.

With the experience from China Pages, he started to imagine a major, China-based business-to-business online e-commerce site that would tie all these businesses together. And sell that vision he could.

In 1999, Jack Ma assembled a group of 18 tech pioneers in his humble apartment in Hangzhou to which he laid out the idea of Alibaba. Soon, Alibaba received (or won) $25 million in venture funding from Goldman Sachs and Softbank as part of a program designed to improve the domestic e-commerce market. It was the start of a long-term partnership with Masayoshi Son.

Like with Amazon, the timing of founding Alibaba was perfect. The internet was taking off and people started to get used to shopping online. China had dove very much into capitalism and consumerism had become a thing.

To address the consumer demand, Alibaba rolled out Taobao, a consumer-to-consumer online marketplace, and Aliwangwang, an instant-messaging tool making it easier for consumers to research and shop for deals. For about six years, Taobao was in loss-making, cutthroat competition with eBay who had announced its expansion into China in 2003. Eventually, Taobao won the fight, forcing eBay to close its Chinese division.

Modeled after PayPal, Ant Financial and Alipay soon followed, filling the circle of Alibaba’s road to dominating the Chinese e-commerce marketplace. Founding Ant Financial seemed a bold move. At the time, China hadn’t yet granted private companies permission to operate in finance. Jack Ma even went as far as to say to his colleagues that if someone has to go to jail, I’ll go.

Alibaba and Ant Financial suddenly had lots of runways when the CCP decided to embark on a campaign of strict internet control, barring foreign competitors like Amazon from entering the market.

In 2008, Taobao announced a spin-off which became Tmall, an online retail platform that finally offered global brands—especially high-end brands—access to an increasingly richer Chinese consumer base. Today, Taobao and Tmall collectively make up the vast majority of Alibaba’s business and sits on the vast majority of the Chinese online consumer market as well.

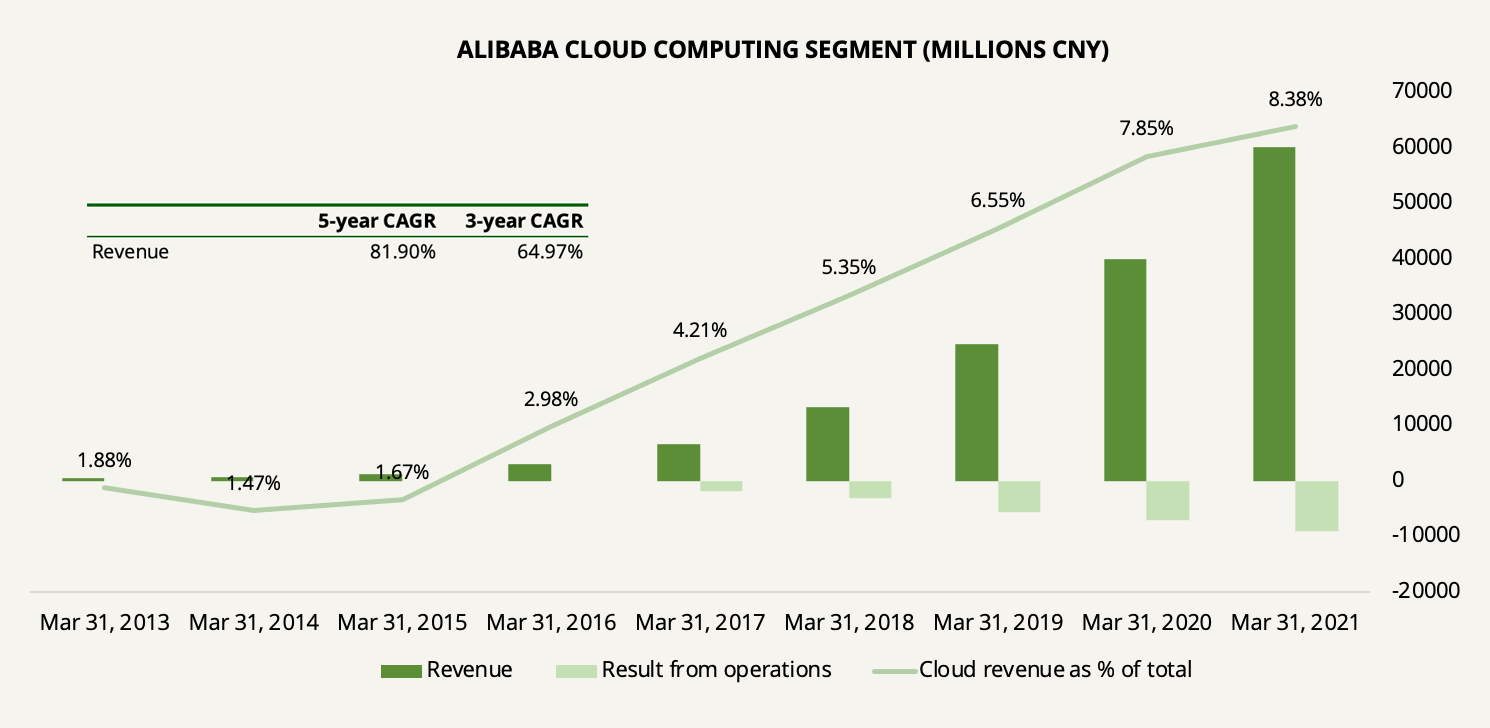

Alibaba Cloud was launched on the company’s 10th anniversary at a time when there pretty much was no existing cloud market in China. Today, the Alibaba Cloud still only accounts for 8% of total revenues in a market that is still in a nascent stage of development. It remains the golden goose for Alibaba.

In 2013, Alibaba and six large Chinese logistics companies went together and established Cainiao, a logistics data platform and global fulfillment network. Cainiao facilitates Alibaba’s entire warehousing and delivery process, making it easier for merchants to manage logistics.

Alibaba went public in 2014 and raised $25 billion. It was the biggest IPO in US history—bigger than the IPO’s of Google, Facebook, and Twitter combined.

In September of 2019, Jack Ma decided to step down as the chairman, handing over the reins to CEO Daniel Zhang, an accountant by training. Jack Ma remained a part of the corporate governing body named the “Alibaba Partnership” which is separate from the board. On the announcement of the appointment of Daniel Zhang, Jack Ma said: [Daniel] has the logic and critical thinking skills of a supercomputer, a commitment to his vision, the courage to wholeheartedly dare to take on innovative business models and industries of the future.

In the fiscal year of 2020, the company passed a long-term strategic goal of generating $1 trillion in GMV globally. In comparison, the current total annual retail sales of consumer goods in China is about $6 trillion.

Alibaba today has one main goal: To not pursue size or power, but to aspire to be a good company for 102 years (at which it would have existed in three centuries). While a noble one, Alibaba can’t run from the fact that it has become mighty powerful.

These are only the rough lines in Alibaba’s history. In the next section, we’ll look at many more of Alibaba’s arms that haven’t been mentioned, including but not limited to Aliexpress, Lazada, Amap, Fliggy, and the New Retail business.

Remember that in the introduction to this write-up, I wrote that Alibaba is the kind of company of which you must look at the business in its entirety to keep your analysis grounded. The company and its sprawling activities are simply so convoluted that you can’t keep track of all moving parts. If that’s your goal, I recommend intensively reading the annual report. Keep this in mind as we approach the value of the company. That said, let’s now dive more into the major drivers of Alibaba’s business and initiatives.

The Arms of the Alibaba Octopus

Alibaba is essentially a digital economy that encompasses commerce, finance, logistics, and big data powered by cloud computing. By providing the essential infrastructure for businesses in all industries pursuing digital transformation, Alibaba has created a two-sided network with consumers on one side and merchants on the other.

This network is huge, it contains major network effects, and the synergies between the businesses in the umbrella are noteworthy. Alibaba likely houses more billion-dollar businesses under its umbrella than almost any company in the world.

To get the right overview, we must look at these businesses the same way they are presented in the annual report which is into four segments: core commerce, cloud computing, digital media and entertainment, and innovation initiatives.

Core Commerce

The core commerce segment consists of both Alibaba’s retail commerce businesses and whole commerce businesses, national and global, while the logistics services and consumer services businesses are also thrown in there.

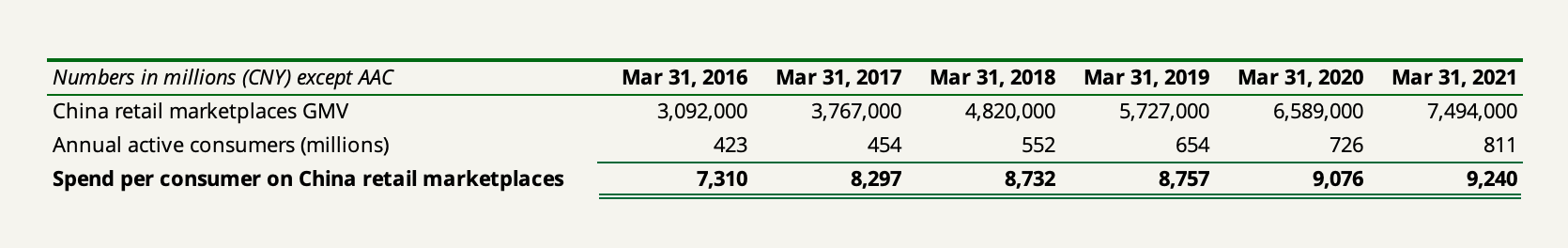

Taobao, the consumer-to-consumer social commerce platform, and Tmall, the commerce platform for brands and retailers, are the two main consumer businesses that make up a considerable amount of Alibaba’s total revenue. Collectively, they are called Alibaba’s “China retail marketplaces”. They generated an astounding GMV of CNY7,494 billion (or $1,144 billion) in the fiscal year of 2021 which is over about 60% of the entire e-commerce market in China. And to get another feel for how huge these retail marketplaces are, here are some peer comparisons: Amazon generated GMV of $490 billion in 2020, Shopify generated $120 billion, eBay $100 billion, while Alibaba’s two main domestic competitors, JD.com and Pinduoduo, generated about $62 billion and $40 billion, respectively.

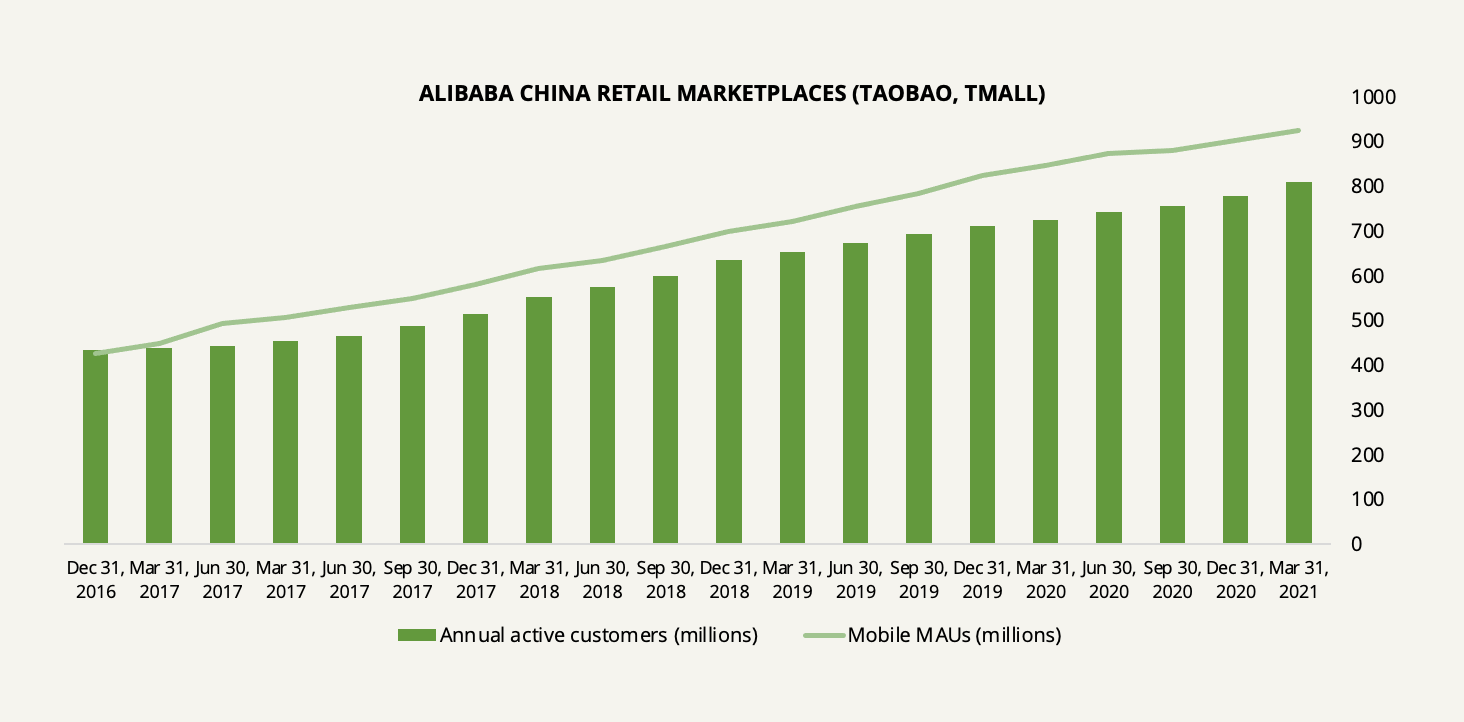

It’s safe to say that Alibaba operates the largest retail marketplace in the world. Collectively the two marketplaces serve a current 811 million annual active consumers (with over 70% of them coming from less-developed areas). The following shows the annual increase in AACs and mobile MAUs since the beginning of 2017.

Taobao is China’s largest mobile commerce destination while Tmall is the world’s largest third-party online and mobile commerce platform for brands and retailers. In the fiscal year of 2021, these China retail marketplaces made up 66% of Alibaba’s total revenues.

There’s quite the difference between the two (although they are highly synergistic and Alibaba cross-promotes to drive traffic between them). While Taobao is a giant consumer-to-consumer community (think eBay), Tmall is a business-to-consumer platform (think Amazon).

But they are not exactly like Amazon and eBay. The majority of items sold on Taobao are new, not second-hand. And for Tmall, you would rather think of it as a giant online shopping mall. Only brand owners or authorized dealers of brands may operate a store on Tmall and several of the bigger brands have “flagship” stores that are aesthetically different than the rest of the Tmall platform. Furthermore, Tmall has become the single best entry point for global brands eyeing the Chinese market with more than 200 luxury brands such as Farfetch, Gucci, and Cartier operating online stores on the platform. Even Costco runs its main e-commerce operation in China through Tmall.

Alibaba continually spins out sub-businesses from the major ones to increase lock-in and customer LTV. Examples include Taobao Deals, which offers attractive value-for-money branded products to price-conscious consumers sold directly from manufacturers, and Tmall Global, which allows Chinese consumers to purchase overseas imported products. Through Taobao, consumers can also access Idle Fish which is a platform dedicated to long-tail items, such as second-hand, recycled, or refurbished products. Taobao Deals is especially noteworthy as it’s growing fast and management has stated a commitment to investing a lot in the business. Annual active consumers of Taobao Deals reached over 150 million in March 2021.

These satellite products sprawling from the major platforms help lock in the consumer because of increased engagement. This is evident in a historically increasing GMV per consumer seen below. Alibaba claims that China retail marketplaces retain 98% of consumers each year.

Next, Alibaba’s China wholesale businesses consist mainly of 1688.com, China’s leading domestic wholesale marketplace with over 990,000 paying members. Alongside, Lingshoutong is a platform that connects FMCG brand manufacturers and their distributors directly to small retailers such as mom-and-pop stores. These China wholesale businesses only contribute 2% to the company’s revenue.

As for cross-border businesses, there’s Lazada, a retail commerce platform for serving over 70 million consumers per year in Southeast Asia. Lazada runs one of the largest e-commerce logistics networks in the region. Alongside, AliExpress allows consumers from around the world to buy directly from manufacturers and distributors in China and around the world. Then there’s Tmall Taobao World, a platform made specifically for Chinese consumers living outside of China to buy from Chinese brands and retailers. And for wholesale, there’s Alibaba.com, where businesses around the world can connect with Chinese manufacturers and distributors.

But we’re not stopping there. Alibaba also operates import businesses such as Koala alongside the already mentioned Tmall Global. Additionally, Alibaba owns Trendyol, a leading e-commerce platform in Turkey, and Daraz, another leading e-commerce platform primarily in Pakistan and Bangladesh. Collectively, Alibaba’s cross-border businesses make up about 7% of total revenues.

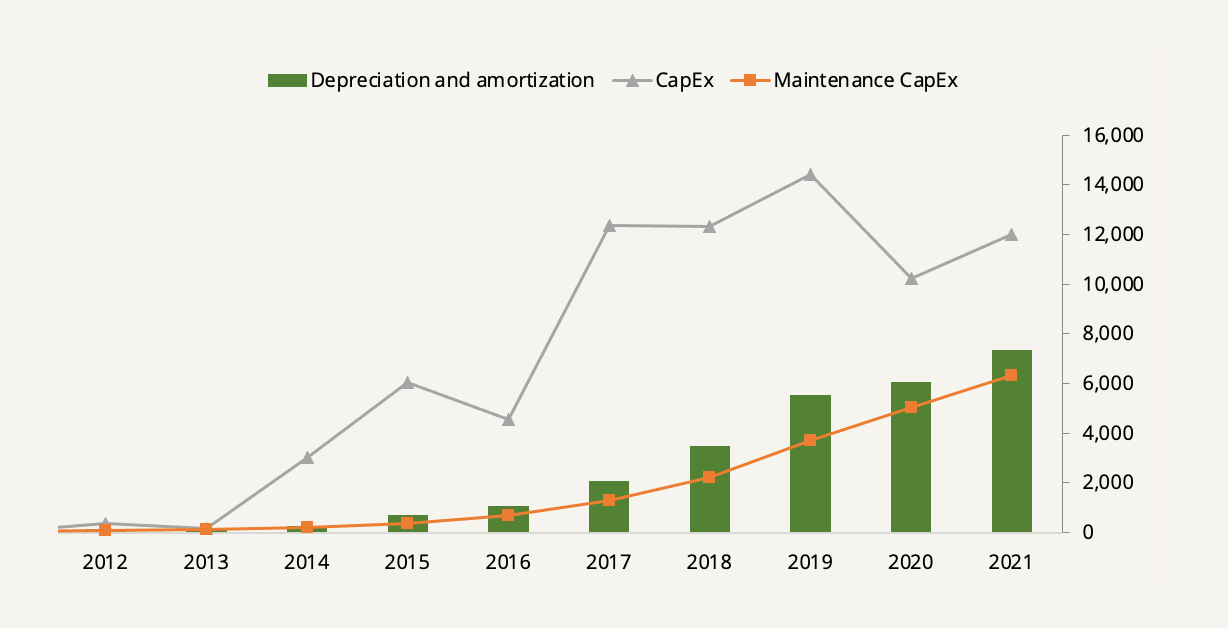

Being very capital-light, Alibaba requires little maintenance CapEx in any of these commerce businesses—retail and wholesale, domestic and cross-border. And here lies the key difference between Alibaba and Amazon (to which Alibaba is often perceived as the Chinese equivalent). While Amazon is focused on first-party sales, Alibaba wants to remain the facilitator of enabling small businesses. Therefore, far more sales on Alibaba’s commerce platforms are done by third parties compared to Amazon. You can see this in the difference between the two’s commerce revenues-to-GMV: 70% for Amazon and 8.3% for Alibaba.

Of course, the result is that Alibaba generates better operating margins on less revenue having far less cost of goods sold. On the contrary, it may also lead to worse user experience from fraud and fulfillment issues.

However, that picture is starting to change a little as Alibaba throws a lot of investment into new areas such as their New Retail strategy which was initiated in 2016. Through New Retail, Alibaba’s goal is to transform offline retailing within under-penetrated categories such as groceries, real estate, home furnishings, and pharmaceuticals into hybrid formats of online and offline models. In 2020, Alibaba bought another round of shares in the leading hypermarket operator Sun Art for $3.6 billion which took its equity interest from 31% to 67% and turned Sun Art into a subsidiary. Together with Freshippo, a membership grocery retail chain (think Costco), Sun Art is now Alibaba’s main platform for carrying out its New Retail strategy. A lot of Alibaba’s incremental investments are channeled into this area. Since physical retail, of course, carries a lot more capital intensity than Alibaba’s main business, we can expect operating margins to come down a little if this initiative would grow substantially.

Furthermore, Cainiao Network is Alibaba’s logistics business that handles the fulfillment for merchants and consumers and provides supply chain management solutions. Cainiao takes care of the entire warehousing and delivery process to improve efficiency across the logistics value chain. Revenue from external customers outside of Alibaba makes up 70% of Cainiao’s revenues, and in the fiscal year of 2021, Cainiao itself comprised 5% of Alibaba’s total revenues.

Lastly, Alibaba operates three main applications within consumer services. Ele.me is a leading on-demand delivery service on which consumers can order food and groceries. Koubei is a restaurant and local service guide platform. And finally, Fliggy is an online travel platform in competition with travel giant Ctrip.

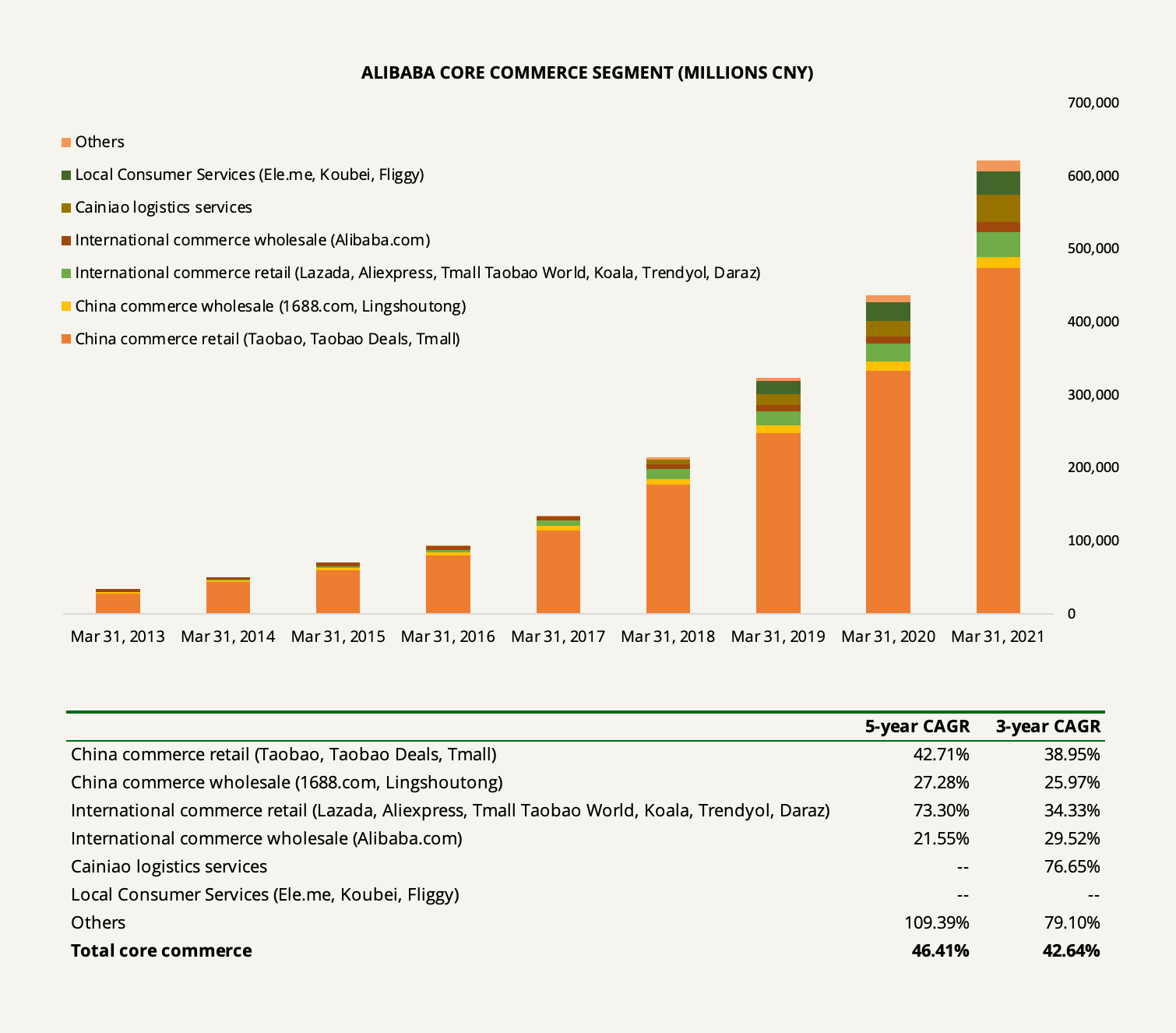

The following is an overview of the businesses operating in Alibaba’s core commerce segment by revenue and each of their 3 and 5-year CAGRs. In the fiscal year 2021, the core commerce segment made up 87% of Alibaba’s total revenues.

Cloud Computing

As mentioned before, Alibaba’s cloud computing division is the golden goose. The cloud market in China is very much at a nascent stage, and by looking at the development in Western markets, there’s a whole lot of runway. My confidence in the Chinese cloud market growing substantially as China moves away from traditional IT infrastructure is high and I think Alibaba will capture a significant share of that.

To get a feel for the development, China’s public could service market generated a measly $19.4 billion in revenue in 2020, accounting only for 0.1% of China’s GDP. Alibaba Cloud takes up about half the market and it’s growing immensely. For the past five years, the Chinese public cloud market has grown by over 60% per year and it’s still only 10% of the size of the US public cloud market.

Alibaba Cloud offers the complete suite of cloud services such as elastic computing, database, storage, network visualization, large-scale computing, security, big data analytics, machine learning platform, and IoT services. In 2020, Alibaba itself migrated its entire core system onto the public cloud.

Alibaba Cloud is the third-largest provider in the world, behind AWS and Microsoft Azure. The two latter basically split the US and Western markets with Azure being the market challenger. I think there’s a good chance that Alibaba will remain the single dominant provider in China and across borders in Asia even as the market matures, and accordingly, I think it will face less competition than its Western peers. I also think that there’s a high probability of cloud computing becoming Alibaba’s most important segment akin to AWS for Amazon.

But that is still years away. 12 years into Alibaba Cloud’s history, the segment is still operating unprofitably as Alibaba pours cash into growing the business. On CNY60 billion in revenue, the division generated an operating loss of CNY9 billion in the fiscal year of 2021.

Digital Media and Entertainment and Innovation Initiatives

The last two segments I view collectively since both of these segments are natural extensions of Alibaba’s strategy to capture consumption beyond its core commerce businesses.

In digital media and entertainment, Alibaba uses data insights from its core commerce businesses to deliver relevant digital media content to consumers. Youku, the third-largest online long-form video platform in China, is included here. As is Alibaba Pictures, which is an integrated platform that covers content production, promotion and distribution, intellectual property licensing and integrated management, cinema ticketing management, as well as data services for the entertainment industry.

As for innovation initiatives and others, Alibaba has created Amap, the largest provider of digital maps, navigation, and real-time traffic information in China (think Google Maps). Amap is widely integrated with Alibaba’s several other local consumer services and has around 100 million daily active users. Additionally, DingTalk is an all-in-one mobile workplace and collaboration platform for working, sharing, and collaborating for modern enterprises and organizations. According to QuestMobile, DingTalk was the largest business productivity app in China by monthly active users as of March 2020. Finally, Alibaba owns the number 1 smart speaker in China which is called Tmall Genie.

Collectively, digital media and entertainment and innovation initiatives generated revenues amounting to CNY36 billion in the fiscal year 2021 making up about 5% of total revenues. And like the cloud computing segment, both segments are currently operating unprofitably having made a collective operating loss of CNY25.8 billion in the same period.

Investments

The last activity of Alibaba worth mentioning is its investing activities. Alibaba makes investments in other companies because they offer technologies or products that will help Alibaba in its operations. By the end of the fiscal year 2021, Alibaba held equity securities, other investments, and investments in equity method investees amounting to CNY247 billion.

Some of these investments include the following:

- Ant Group in which Alibaba holds an equity interest of 33%.

- Bilibili, a listed video streaming platform in which Alibaba holds an equity interest of 8%.

- STO Express, one of the leading express delivery services companies in China in which Alibaba owns a 25% equity interest in addition to a loan made with a remaining value of CNY3.5 billion.

- Mango Excellent Media, an audiovisual interaction-focused new media service platform in which Alibaba owns a 5% equity interest.

- China Broadcasting Network, a telecommunications company in which Alibaba owns a 7% equity interest.

The most prominent here is, of course, Ant Group, because it handles all of Alibaba’s payment processing and provides a wide range of financial services to the company’s consumers as well as merchants. Alibaba’s ownership of Ant Group is accounted for using the equity method with a significant carrying value of CNY90.7 billion.

How Alibaba Monetizes Its Ecosystem

When innovating new initiatives that could potentially strengthen the ecosystem, Alibaba puts the customer experience first. After that, the monetization of the initiatives becomes a longer-term strategy.

As evident from the previous section, Alibaba makes the vast majority of its revenues (and profits) from the core commerce segment—more specifically, its China retail marketplaces. The monetization platform Alibaba uses for letting merchants market on these platforms is called Alimama. Alimama handles all of Alibaba’s pay-for-performance (P4P) marketing services such as search rankings, display marketing, and affiliate marketing campaigns. Alimama also operates the Taobao Ad Network and Exchange (in short, TANX), a large bidding exchange automating the buying and selling of tens of billions of marketing impressions daily.

Meanwhile, Alibaba makes commissions on transactions made on Tmall. The commission percentages typically range from 0.3% to 5.0% depending on the product category. It charges no such commission on Taobao—a strategy that largely contributed to Taobao winning the competition against eBay in the early years.

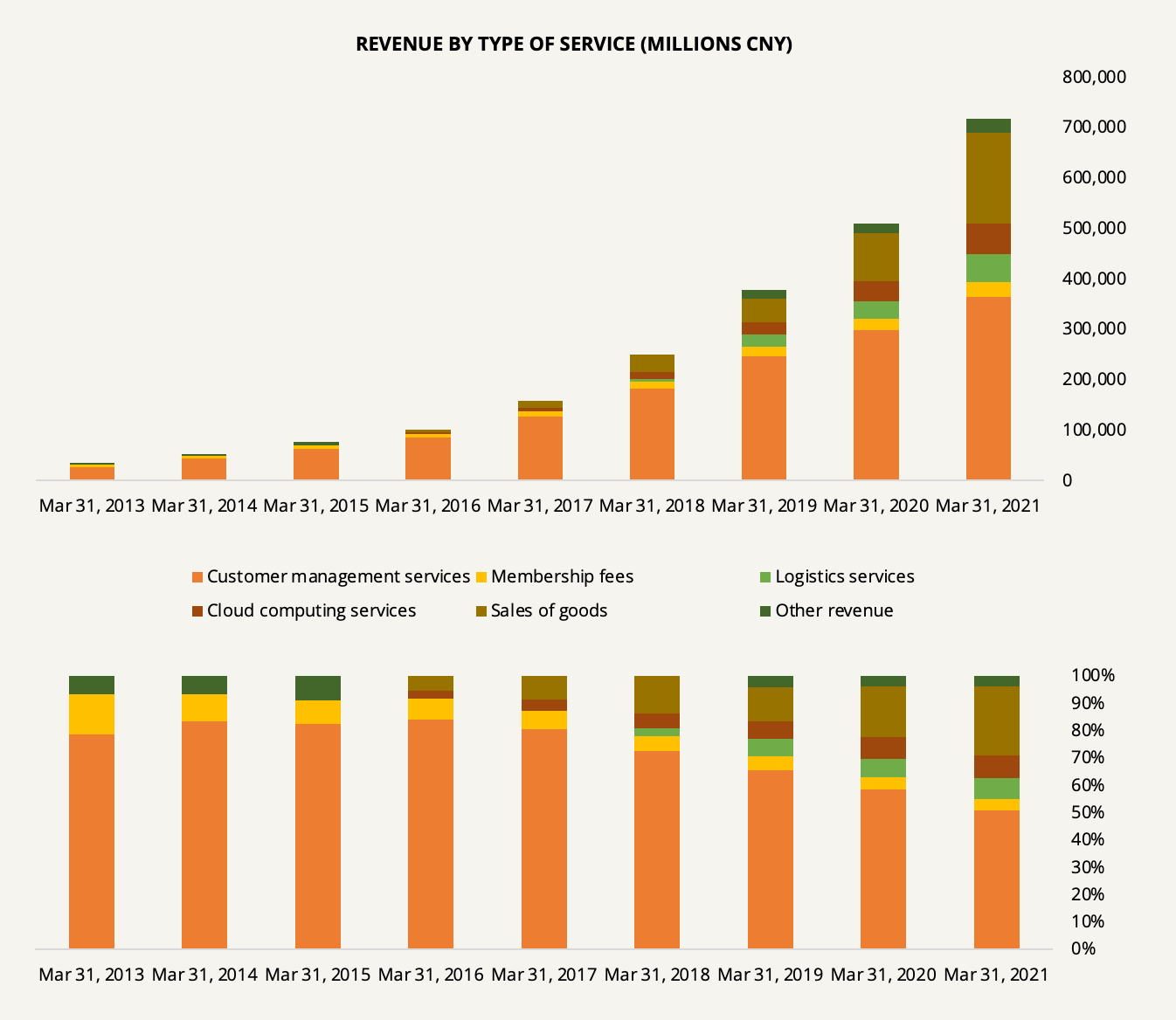

Collectively, Alibaba terms these types of revenue as customer management revenue (CMR). And as shown below, CMR takes up a considerable amount of total revenues, although it has come down a lot as Alibaba has diversified revenue streams into new initiatives.

Keep in mind that CMR growth has a linear relationship with GMV growth. So as other segments and businesses will keep growing faster than the relatively mature core commerce segment, I would expect CMR to contribute an increasingly smaller share of total revenues going forward, although still growing fast. Which is not a bad thing at all.

The Bigger View

Let’s take a step back and look at the company in its entirety.

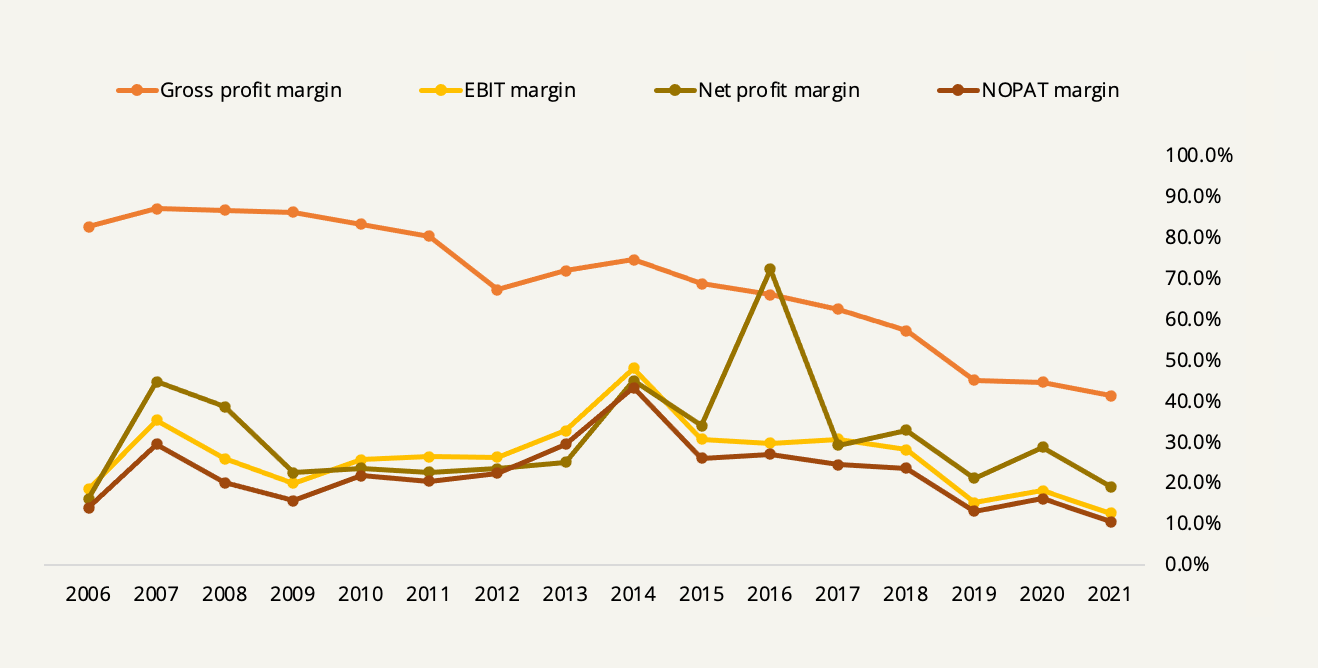

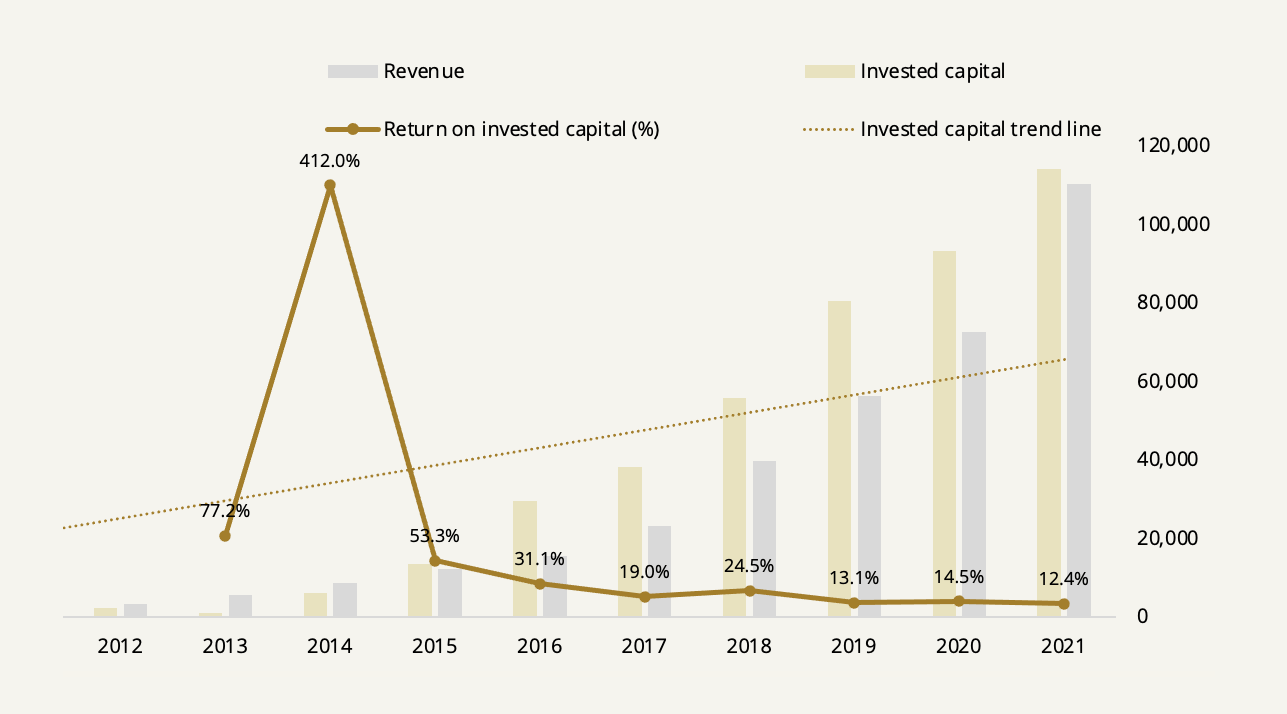

When Alibaba became listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 2014, pretty much the only business behind the company was its domination in online marketplaces, fueled by networks effects and essentially non-existent reinvestment. The company spent little on marketing costs and its R&D and development costs were negligible. These factors resulted in a stratospheric EBIT margin of almost 50%. Since then, as the ambitious ceiling was raised and Alibaba kept expanding into social media, offline retailing, and expansive logistics infrastructure, the natural development has been slowly decreasing margins.

As shown below, you see the same effect as the company’s invested capital base for some years increased at a faster rate than revenue, lowering the capital turnover to a current level of 1.2 (taking the invested capital base at the beginning of the year).

Furthermore, if we look at the capital expenditures (with M&A activity included), we accordingly see that Alibaba is spending a lot on growth CapEx, particularly in the years following the IPO.

Alibaba is obviously investing a lot in the future which we already established. Now the question becomes whether the company is investing too much. I have reason to believe that it does not.

Alibaba’s Moat Is in the Infrastructure

As you should have noticed by now, Alibaba owns a dizzying number of businesses. But the most important thing to know is that synergy is at the forefront of anything Alibaba creates. Any innovation must fit into the big picture of making the daily lives of their customers—be it consumers, merchants, or others—more efficient.

We have made, and intend to make, strategic investments and acquisitions. We do not make investments and acquisitions for purely financial reasons. Our investment and acquisition strategy is focused on strengthening our ecosystem, creating strategic synergies across our businesses, and enhancing our overall value.

Alibaba 2021 Annual report

The moat that is now a result of the stickiness of this entire ecosystem comes from decades of investment and innovation and is driven by three key factors: first-mover advances into nascent industries supported by a cash cow in the core commerce business, network effects, scale effects with significant operating leverage, and market barriers to entry helped by the government.

The outcome of such factors is a deep moat with a very long runway in a huge country where internet penetration is still low. Jack Ma and the founding management were at the right place at the right time and fiercely grabbed that opportunity. Every year, the moat that they built is being widened by a margin as Alibaba continues to make significant investments in the platforms. Alibaba has a big-pocket competitive advantage from its high operating leverage and margin levels from the core commerce business which is what enables it to make strategic investments that burn cash in the short term but strengthens the moat over the long term.

In turn, the incomparable penetration of Alibaba’s ecosystem in China offers the company a significant advantage from extensive consumer insights. Combined with its cloud computing technologies, supply chain management capabilities from operating Cainiao and its New Retail businesses, as well as sales and marketing systems, Alibaba has got the perfect tool for facilitating the digital transformation of pretty much any business in China. And pretty much any business that Alibaba transforms becomes a sticky customer.

But a moat can not only be defeated by competition. Other external forces may be the cause. As for Alibaba, the long-term threat may be the very thing that helped create its moat. Which now leads us to the mental model of inversion.

How Could Alibaba Fail?

In this section, I will provide a discussion of the three main risks that may potentially undermine Alibaba’s businesses in any meaningful way. Keep in mind that I do not wish to convey political speculation in this discussion. I have little to no idea of what will happen. The sole purpose of discussing political uncertainties is to gauge the risks inherent.

Delisting Risk

We begin with what I believe should be the least of the worries of any long-term investor. Of course, a potential mass delisting of U.S.-trade Chinese equities matters in the short-term—certainly in terms of quotations. But it shouldn’t be a concern in terms of intrinsic value.

The effort by the SEC to gain access to audits of overseas companies, which began under Donald Trump, is continuing under Joe Biden. Obviously, it makes sense that the US would want to audit the books of the companies trading on its exchanges. For one thing, it’s a matter of law. The 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act, enacted in the wake of the Enron scandal, required that all public companies submit to inspections of their audits by the PCAOB. The problem intensified when Luckin Coffee, which was listed on NASDAQ, was found to have fabricated more than $300 million in sales. Luckin Coffee subsequently filed for bankruptcy protection after being fined $180 million by the SEC.

None of the big four accounting firms’ China divisions have yet to comply with the request, citing China’s national security laws prohibiting them from turning over the books. The U.S. has responded with threats of mass delisting all Chinese equities—which is more than 200—from its exchanges.

Any delisting would take at least three years to enact, since, according to a law signed by Donald Trump in December 2020, a company would have to be in non-compliance with audit inspections for that number of years to be delisted. Some of the U.S.-listed Chinese companies have done a second listing in Hong Kong to prepare for it—Alibaba included.

If no mid-way solution is found—e.g. a co-audit solution introducing a second audit firm that can be inspected by regulators—I think it could come down either way. While it could be argued that the interdependence of the U.S. and China is too high to make delisting imminent, I also think the U.S. will put a lot of value on the integrity and functioning of their financial markets.

I don’t know whether Alibaba will be delisted in three or four years but investors must be aware of the possibility. Nonetheless, worse things can happen in three years.

Crackdown Risk

I do think there’s quite a difference between how China’s crackdown is perceived in China and Western media. China is doing a lot of what it thinks will help their country while Western media kind of makes it seem like they’re trying to destroy their own stock market and domestic companies. Therefore, to better understand how political risks may play out in the long-term in China, I believe it’s vital that one thinks in terms of China’s objectives and incentives.

What is interesting about China is that it’s both one of the oldest civilizations in the world and one of the youngest countries in the world. The latter shows when it comes to regulating a market economy and a modern thing like the Internet.

Its youth means that China has the opportunity to create a modern regulatory framework that isn’t burdened by a web of outdated rules from a previous Industrial Age. It can create a framework that better matches the current time, technologies, and people’s aspirations. Comparatively, the U.S. is burdened by a legal framework rooted back from when they were trying to regulate the big oil and steel companies in the 1890s. When you got completely new types of businesses blossoming from the Internet age with freemium models and what else, it’s not a bit easy to regulate based on such a framework. Richard Epstein has argued that the greater the complexity of a system, the simpler the rules that govern it must be. China has the better opportunity to create a simpler, more effective system, granted that it does it right.

I think that is what the CCP is trying to accomplish but I also think it tries to have things both ways. At China’s Third Plenum in 2013, Xi declared that market forces would have a “decisive” role in allocating resources, while at the same time the state sector would have a “leading” role. It’s not easy to figure out how that might play out.

China’s objectives lean on its political problems. Its demographics will face a serious drag as a consequence of a central planning mistake of the one-child policy made decades ago, the nation’s overall debt has grown to an impressive 270% of GDP, the environment is bearing greater stresses, and there’s a going discontentment with China’s way of handling social issues from abroad.

The demographics problem is a big one that has crept into China’s education system and created a mess. Due to immense pressure and aggressive marketing from after-school programs, education has become a thing for the well-off since rural kids that couldn’t afford fancy after-school programs would have little to zero possibility of getting into any form of tertiary education. The market for after-school programs has become bigger than the total public cost of schooling and now China wants to have a say about how that education is run.

The growing debt is also a big one and China has an incentive of keeping control of its financial system. There are two reasons for that. One is the CCP’s traditional intentions of central planning and the other is to keep the financial system from running amok at a time where the national debt perhaps is at a fragile level, the economy is slowing down, and the country faces geopolitical headwinds.

China has undergone a fintech revolution like no other of which WeChat Pay and Alipay have become the most common methods of payment in China. It’s a thing great for the economy and the Chinese people but it makes it hard for the CCP to track transactions. Of course, the CCP is nervous about financial risks and it would be no time to be calling, as Jack Ma did in his Bund Summit speech, for a loosening of the system. It made little sense that fintech giants such as Ant Financial could cleverly avoid capital requirements that other banks were held to. China’s crackdown on the payments has a lot to do with the CCP wanting to avoid having to write up a Dodd-Frank Act at home.

Furthermore, there’s a tit-for-tat dynamic going on in terms of national security. China’s reasons behind the Didi Chuxing case have many parallels to Western moves targeting specific Chinese companies such as Huawei, ByteDance’s TikTok, and Tencent’s WeChat. The trend is that cautiousness comes before everything else when it regards national security, even if rational or not. In China’s case, it was enough to spark a crisis in one of their tech giants which transmitted to price panic in several other Chinese equities, including Alibaba. Of course, China had an additional incentive to have Didi list domestically rather than overseas. The tit-for-tat dynamic has triggered a governmental incentive to build up domestic technological capabilities and they want these capabilities to remain in China.

However, China faces a lot of the same issues as its counterparts in the U.S. and Europe in terms of monopolies, data privacy, labor standards, and housing costs. And compared to Western countries, Chinese companies such as Alibaba and its peers have had several degrees of freedom to do what they wanted based on an opaque legal framework. But I also think that it’s due to China’s “clean slate” that they have moved much faster than Western nations in taking up antitrust issues, including Alibaba’s antitrust fine.

For these reasons, my view of Alibaba’s future in light of the Chinese political landscape is the following.

I don’t think Alibaba stands much in the way of the CCPs political incentives in the near to mid-term, except for my last point on imminent additional antitrust issues. Therefore, I don’t think things have necessarily changed in any huge amount except to the extent that regulatory issues will become regular bumps in the road. So while Alibaba will continue doing what it is doing because, by and large, Alibaba is critical to China and is doing good for society, I do think management will be much more attentive to regulatory compliance by a significant margin. This will in turn result in more reinvestment and less profit, at least in the short term.

Risk from Competition

There is a wide moat around Alibaba’s business for reasons already discussed but the competition is getting smarter.

What I found interesting reading the annual report was that the only competitor mentioned was Tencent since Alibaba obviously faces two other strong competitors in JD.com and Pinduoduo. Meanwhile, albeit less threatening, Alibaba Cloud competes with Huawei and Baidu.

One could argue that Alibaba historically has ridden a period of relatively muted competition. In many ways, JD.com is most similar to Amazon because the company does first-party sales, thereby taking a bigger share of the GMV it generates while reducing margins. JD.com also owns its own fulfillment network and offers a Prime-style membership. And because of its close partnership with Tencent which gives them very attractive placements within Tencent’s app network. Additionally, they’ve partnered with Walmart to offer same-day delivery in selected areas.

Pinduoduo is quite different from any other big e-commerce company since the company has introduced a novel concept of online group buying. It works so well in China because of its huge rural areas looking for cost savings by buying in bulk. You can compare a lot of Pinduoduo’s business to Costco and it’s interesting how it will play out.

I won’t get more into the competition here. What’s important to know about the competitive dynamics in China is that there’s a huge splurge of commercial innovation going on while there’s still massive opportunity in reaching the lower-income population that is still on its way to get on the internet. Alibaba has got strong competitors in Tencent, JD.com, Pinduoduo, and Amazon within and across the border.

That said, I think Alibaba’s moat around its current business is rather impenetrable and competition will not be Alibaba’s ruin. But I also think there will be plenty of space for more market players and that Alibaba will have a harder time growing from here in its core commerce business—perhaps slightly below the growth of the market. And that is why the company is doing just the right thing in expanding into broader value activities and focusing on cloud computing as the battle for the future.

Valuing Alibaba

There are essentially two ways in which we could value Alibaba: the complex method or the simple method—each arriving at the same value if done correctly. The simple method is looking at Alibaba in its entirety while the complex method is taking the sum of the parts of all of Alibaba’s individual businesses.

I choose the simple method for three reasons.

First, while making godly returns, core commerce is Alibaba’s only profitable segment. The other segments are buckets in which Alibaba throws cash at strategic investments that strengthen the ecosystem with the intention of them earning positive returns on capital invested in the long term. Many of these strategic investments have option-like characteristics and I wouldn’t know how to value them one-for-one.

Second, these businesses are intentionally highly synergistic. As for the marketplaces, traffic flows between them and Alibaba capitalizes on cross-selling opportunities allowing for lower acquisition costs, stronger lock-in effect, and so forth. The result is that the majority of the businesses are worth more in Alibaba’s fold than if divested, and they should thus be viewed collectively.

Third, valuation precision matters little due to reasons established in this write-up. The span of uncertainty of Alibaba’s incremental investments is high and there are political risks we can’t measure effectively. What matters most is whether we can see a substantial margin of safety in the price we pay. For these reasons, it pays to keep the valuation simple.

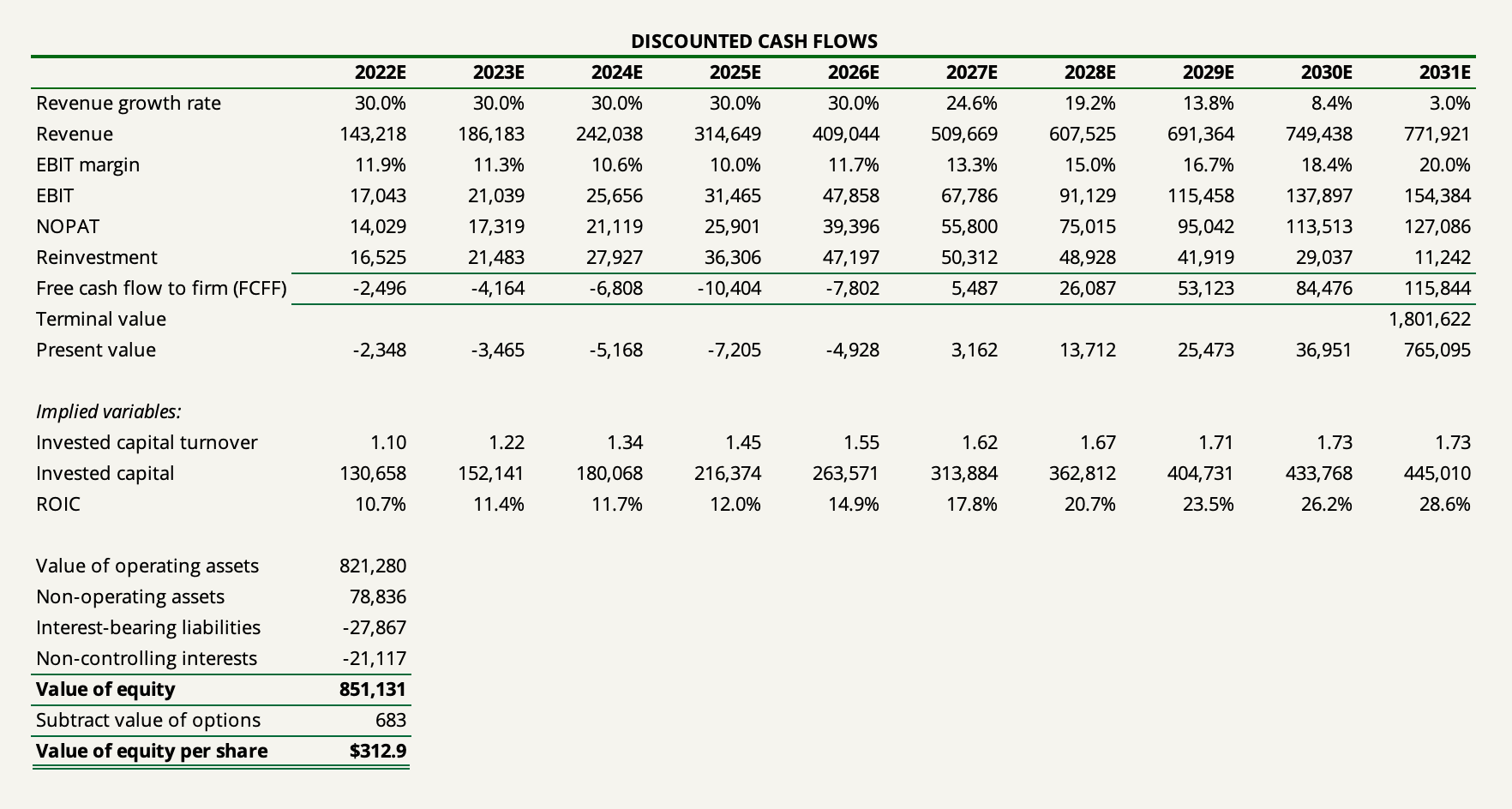

The following are my main assumptions based on what we’ve established.

Revenue Growth

Revenue growth will remain elevated with slight losses in China core commerce market share which will be more than offset by increases in diversified revenue sources with a special emphasis on the rapidly growing cloud computing division. I assume a high growth period of 30% growth in the first five years gradually decreasing to a terminal growth rate of 3% in the remaining five years.

Operating Margin

I assume that Alibaba’s EBIT margins will remain compressed with a slow decrease to 10% over the next four years, partly from regulatory pressure and partly suppressed by the company’s segments aside from core commerce. Subsequently, starting in year five (2026), investments in cloud computing and innovation initiatives will gradually begin to pay off so that the EBIT margin will increase to 20% over the next six years primarily led by continued network effects and operating leverage in the core commerce business and the future state of the cloud division. (In comparison, Amazon’s AWS division earns an EBIT margin of around 30%.) While a gradual rise to 20% will be an improvement, this is far from Alibaba’s previous earnings-generating ability, reflecting not only a transformed business but also increased pressure from regulatory compliance and competition.

Reinvestment

In line with increasing margins, Alibaba’s reinvestment will turn more efficient as the new businesses mature. The company currently generates CNY1.2 in revenues for every CNY1 in capital invested. Going forward, I assume that for every CNY2 in incremental revenues, Alibaba will have to invest CNY1 in invested capital. This will gradually raise the invested capital turnover over the 10-year period.

Cost of Capital

Assuming the current capital structure of 95% equity and 5% debt going forward, an opportunity cost of equity of 10%, and an after-tax cost of debt of 2.46%, we use a weighted average cost of capital of 9.62%.

Taking the value of operating assets of $821 billion, adding non-operating assets of $79 billion, subtracting debt and non-controlling interests of $28 billion and $21 billion, respectively, we arrive at an equity value of $851 billion. And by also subtracting the small value of options granted to employees, it works out to a value of $313 per ADR.

When I added Alibaba to the Junto portfolio on July 26, it was at a price of $191.81, suggesting a significant margin of safety.

A Note on Position Sizing

Members of Junto know that the Kelly criterion is an important part of my investment philosophy and how I size my investments. I would like to explain a bit of the process behind the Kelly criterion in terms of Alibaba.

When I bought my shares, the purchase had a portfolio impact of 8.23%, meaning Alibaba weighted 8.23% of the portfolio at entry. It was a marginally larger position than my other Chinese holdings. But while I probably will not buy more of my other Chinese holdings, I might buy a lot more of Alibaba at the right prices. In fact, I would be willing to let Alibaba weigh 20-30% of the portfolio, should the right circumstances present themselves.

The difference lies in the two variables which determine the Kelly criterion: my sense of the probabilities involved and the edge I have to the extent of those probabilities.

Compared to my other Chinese holdings, the moat around Alibaba is bigger and the downside is smaller. The result is that my confidence (probability) of being right is higher.

My edge depends on the price I pay. As a rough example for Alibaba, I may feel that there’s a 75% probability that the company is worth my valuation of $313 per ADR. The price paid of $192 per ADR represents the downside, and thus the payoff is 1.63-to-1 (313 divided by 192). Taking the edge, which is the payoff times the probability of winning minus the probability of losing, and dividing it by the odds of 1.63, the Kelly criterion suggests betting 60% of the portfolio.

Now, all the Kelly criterion does in this case is to suggest that the odds are heavily in my favor. While I wouldn’t bet 60% on Alibaba, it does mark the ultimate upper bound. In this case, I apply a 50% margin of safety to the criterion which is why I’d be willing to bet up to 30% of the portfolio. The difference between the position size in Alibaba and my other Chinese holdings does not lie in the margin of safety inherent in the price more than it lies in my ability to determine the right probabilities.

Because investing is a dynamic discipline, there are some caveats around the Kelly criterion which makes it more of a thought experiment than a mechanic exercise when applied to investing. Here’s a more in-depth article on the subject.

Ending Remark

You can have cheap stock prices and you can have good news. But you rarely have both at the same time. For you to buy cheaply there must always be some fear of things going wrong. This is why there are currently lots of opportunities lurking in China and little in the U.S. The ponds of opportunity change all the time and you have to fish where the fish are.

Of course, you can expect volatility—not just in the price of Alibaba but any of the holdings in the portfolio. Though, I welcome volatility for the same reason that I can buy cheaply in the first place. You have to pay the price of volatility to reap superior returns in the long run. And this is where this little mental trick comes in handy.