Even though Total Specific Solutions (TSS) only belonged to the Constellation family from 2013 to 2020, the company’s history spans almost two decades. Founded (or rather acquired) in 2006 by a family office run by the Dutch Strikwerda family that earned its money from selling an IT company, TSS was in many ways already Constellation’s European twin before it was acquired: a growthy, decentralized serial acquirer of VMS businesses that uses permanent capital and offers complete autonomy to the acquirees.

By the time TSS was swallowed up by Constellation, it had grown into the largest VMS company in the Netherlands. To Constellation, it was so big a purchase (price of €240mn, 3.4x total tangible assets, and 2.7x 2013 net maintenance revenues) and it reached so many verticals that it, with its 1,400 employees, came to form an entirely new Operating Group within the company.

And once TSS got into Constellation’s fold, the M&A machine was fired up. In its seven years pre-Constellation, TSS had made seven acquisitions, but under Constellation, it completed 60 of them the following six years, turning TSS into a prominent Operating Group. When Constellation therefore announced that TSS would be spun off and that the company would make a big acquisition of the Dutch VMS growth company Topicus.com B.V. in the process (while taking the target company name), it was something that drew attention from the geeky value investing community. Could Topicus become the next Constellation, repeating the story once again but on the other side of the Atlantic?

[Note: In the following, when I refer to the consolidated entity, I use “Topicus”, when I refer to the acquired company prior to the TSS spin off, I use “Topicus.com B.V.”, and when I refer to the Topicus Operating Group, I use “Topicus Operating Group”.]

On the face of it, it might seem so. Topicus carries on Constellation’s ethos and methods. It acquires VMS companies with growth potential, aims to manage them well through autonomy, and reinvests the free cash flows coming out in new internal Initiatives and acquisitions of other VMSs. Other than getting a rich parent, Topicus appeals as an acquirer to potential acquirees in Europe because the acquired VMS can continue operating as they always have but gain access to all best practices related to software development and market insights from the parent company’s other business units within the same vertical. For instance, an insurance VMS can piggyback the best practices from another insurance VMS when creating a new software solution to the insurance industry that fully complies with regulations—which can be a cumbersome task across Europe—cutting valuable development time and costs and increasing the value proposition to potential and existing clients.

One has reason to believe that this form of ownership transition matters more in the VMS industry than other industries, precisely because the kind of VMSs that Topicus (or Constellation) acquires sell mission-critical, sticky (90%+ retention), and highly customized services. It’s always an obligation for a seller of a VMS to assess whether a potential acquirer is the right one or whether another owner can add more value to the business for the benefit of customers and employees. To the customers, this issue can easily be a matter of whether to cut the tie with the vendor since the VMS is such an important part of their business and the slightest distrust in whether things are going to continue smoothly could be enough to start working with a competing vendor. For perpetual owners such as Topicus, this is a major M&A advantage I wish I’d emphasized more boldly in the Constellation write-up.

The main reason why this advantage works is due to Topicus being constructed in the same decentralized fashion as Constellation, with a thin top layer and bunches of Business Units operating and cooperating beneath shared Operating Groups which keeps customer loyalty and prevents overhead creep. Headquarters doesn’t mess with how the Business Units operate and the BUs trust Headquarters and the Operating Group level to manage the capital they won’t need to keep their own denominator down in the ROIC calculation.

As opposed to Constellation’s six Operating Groups (of which the acquired Topicus is one of them), Topicus has three. The TSS part of Topicus has over 105 independently managed BUs and employs over 3,900 people. It’s split into two Operating Groups, TSS Public and TSS Blue (serving the private sector) while the acquired Topicus.com B.V. constitutes the third Operating Group with about 900 employees.

Besides the operating structure, Constellation’s incentive system is also copied and pasted, seemingly because it works so well at fostering an ownership culture and prevents reckless capital allocation behavior. Employees above a certain compensation threshold are required to purchase stock in the open market and these shares are locked for a period of up to four years. Bonuses are intelligently tied to a mix between ROIC and net revenue growth so that Managers are incentivized to carefully balance the fine line between sending excess cash to the Operating Group or reinvesting it in new Initiatives. At the Operating Group level, the same system applies. Topicus’ Portfolio Managers constantly decide whether to meet the hurdle set by Headquarters by reaching for ROIC or net revenue growth. By keeping too much cash, the Manager might reach for net revenue growth in low-value opportunities, but ROIC suffers. On the contrary, by sending too much cash to Headquarters, ROIC might go up, but net revenue growth suffers.

Given the fact that one can’t help but compare Topicus to Constellation (which is both a blessing and a curse for the company and its management), let’s take a look at some of the drivers that I went through in the Constellation write-up. So far it looks promising.

Intrinsic Value Growth

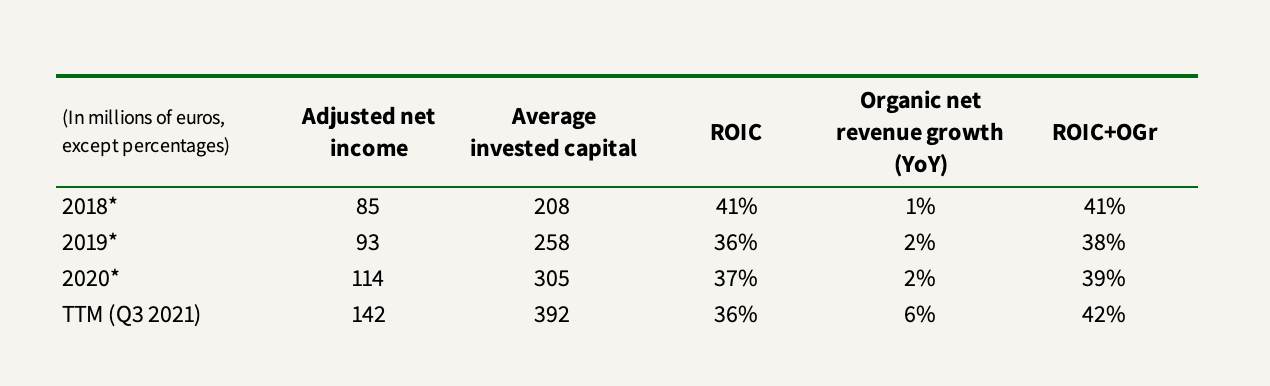

*Taken as Constellation Software Netherlands Holding Coöperatief U.A.

The company provides neither the invested capital figure nor the adjusted net income figure in its reports. So I’ve calculated invested capital as equity + interest-bearing liabilities – cash while adjusted net income is calculated as net income + amortization + redeemable preferred securities expense.

ROIC+OGr is a very important number. While investors can’t really use ROIC+OGr as the right proxy for growth in intrinsic value with Constellation anymore, they can safely do so with Topicus. Three things determine whether it’s useful as a proxy: that the business remains capital-light, that the economics of the acquisitions can be expected to be similar to those in the past, and that the company can continue to reinvest all or more than its FCF. Due to its small size, I would expect Topicus to live up to these prerequisites for years into the future.

Now, there’s a catch. Note that my calculation for adjusted net income—which is used in ROIC—is not GAAP or IFRS consistent. To many investors, “adjusted earnings” is notoriously known as a term that’s equal to trouble and thrown into the “bullshit earnings” bucket. In Topicus’ case, that would be a mistake. Simply looking at net income vastly understates the company’s earnings power since amortization charges take up a large part of an acquisitive technology company’s income statement (in Topicus’ case amortization exceeded net income in fiscal Q3 2021). When you ignore amortization charges by adding them back to net income, you implicitly assume that the economic life of the asset amortized is perpetual. One way to test this assumption in the VMS business is to look at whether the maintenance revenue base is growing or shrinking organically. While Topicus doesn’t decompose net maintenance revenue growth in the reports, we can look at the organic growth picture of the revenue stack to get the picture.

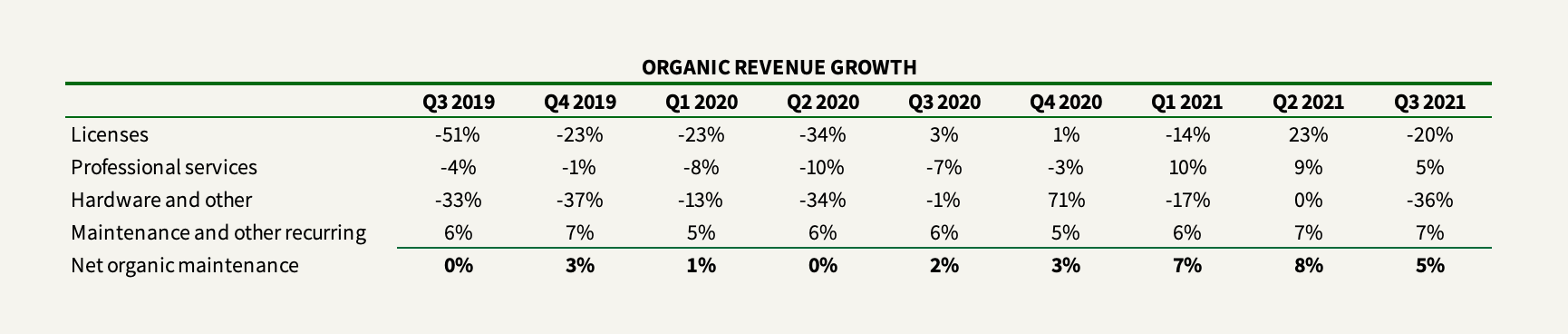

Organic Revenue Growth

There is a good indication that the economic life of Topicus’ intangibles does not suffer from time as conventional accounting would lead one to believe. Meanwhile, as we’ve seen at Constellation, one would expect maintenance revenue to comprise an increasingly larger share of net total revenues (maintenance revenue comprise 70% of the stack at both companies) as is the nature of operating with sticky products in niche verticals that grow consistently. The result of that will be long-term margin expansion since maintenance revenue comes with very high incremental margins.

Now, what’s going to be interesting to gauge is whether the Topicus story will be as much about disciplined capital allocation rather than exceptional operational performance as much as Constellation’s story was/is. The Topicus Operating Group differentiates itself much from the TSS Operating Groups. In the Topicus Operating Group, the company has a high-flying, experimental innovator building many of its services from scratch by hosting competitions in which the best in-house ideas get funded. In its annual competition, Race 2 Make It Real, the employees divide into teams and race to turn ideas into products. The business is one that seems to figure out a lot of Initiatives and might continue to grow organically as it historically has by >10% servicing verticals in education, finance, and healthcare.

So with little else to back up my claim, I have the feeling that the Topicus Operating Group’s organic growth culture and open-ended opportunities can/will/should rub off on TSS in which organic growth might become a higher priority than it is at Constellation. Likewise, TSS’ acquisitive nature may rub off on the Topicus Operating Group in which its organic growth may fall slightly as the business grows and more efforts and human capital are deployed on acquisitions that involve a higher hurdle (as safe, quantitative bets) rather than funding in-house innovation that might involve foggy estimates for return on capital. If that’s the case, you will likely see CapEx spending and expensed investments go down in which the Topicus Operating Group’s single-digit EBITDA margins will approach something that looks nearer to TSS’s +20% margins while the consolidated Topicus margin might expand a few percentage points from its current 14% (Constellation does 17%). Consequently, you will see those contingent investments, a big part of which flow through the income statement, being funneled to further acquisitions instead. To what extent this will be the case or whether the Topicus Operating Group will run its own show on the side of TSS, I don’t know. I’m just trying to ballpark two scenarios. Either case can be equally as value-creating in the long run given that the team at the Topicus Operating Group elects to pursue organic Initiatives which doesn’t fail to meet the overall hurdle rate.

The capital allocation issue leads us to the elephant in the room: Topicus doesn’t have Mark Leonard at the steering wheel, but instead Daan Dijkhuizen, the previous CEO of the acquired Topicus.com B.V., who doesn’t have much capital allocation experience but who has shown excellence in operating performance. Following Mark’s footsteps, or at least the shareholders’ expectation of doing so, are major shoes to fill. When you deal with an organization that is largely dependent on human capital and growth by acquisition, great leadership tends to ripple down throughout the organization as a battery jumpstarting a system while bad leadership can be enough of a factor to make an organization’s well-designed incentive system lay idle. Mark Leonard is arguably one of the greatest CEOs of all time so there’s no wonder the system works seamlessly at Constellation.

In terms of capital allocation performance, will the key man factor matter, though? At Constellation, Mark already gave up capital allocation control in 2005 after which incremental returns on capital from M&A have only expanded, not contracted. And this astonishing feat has been a result of Constellation’s ability to distill acquisition processes down to steps, checks, and balances which can be used and applied by every one of the company’s Portfolio Managers and further taught to the next gen. So ostensibly, Constellation’s capital allocation framework should continue to work as long as there are niche VMSs to buy at attractive prices, not whether there are enough competent Portfolio Managers to find and train. (I’m not saying that intelligence, energy, and integrity—three rare but vital attributes of a capital allocator—are not required to apply Constellation’s methods. What I am saying is that, based on the Constellation story, prospective acquisitions are likely to dry up first.)

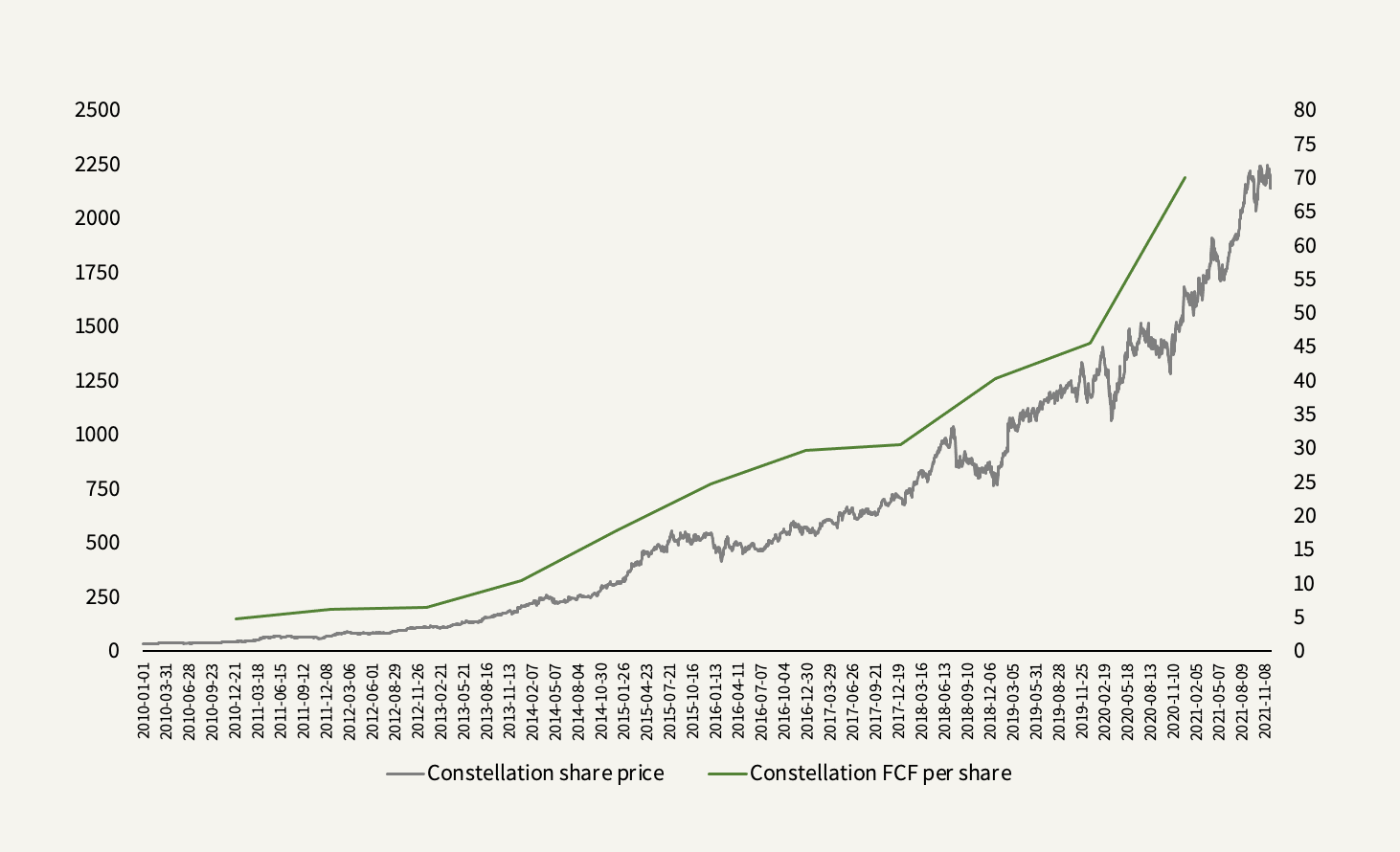

So for Topicus, there’s this scale advantage but it’s in reverse. Due to its small size, Topicus has lots of runway to pursue to the point where you can pretty much compare it to where Constellation was a decade ago. Topicus generated €90mn of FCFA2S in the past four quarters whereas Constellation generated FCF of CAD$101mm a decade ago in 2010—a year in which it completed 34 acquisitions. And the fact that Topicus runs three Operating Groups whereas Constellation runs six at almost 10x the revenue size tells that there’s vast room for expansion within each.

The scale advantage implies that Topicus isn’t burdened by thinking about other capital allocation options other than just buying all the VMSs it can find because it doesn’t need to lower its hurdle just yet. And the good thing is that the company will likely know when it’s time to do that. Benefiting from the knowledge and experience accumulated at Constellation, Topicus can prevent the one mistake Constellation did during the past decade which was not lowering the hurdle rate in due time (the consequence of which has forced Constellation to grow its cash balance and pay multiple special dividends since 2014). But with its puny capital of €500mn, Topicus has a long way to lower the hurdle and can likely pursue acquisitions at the +25% IRR level for years before return constraints kick in.

Better yet, Topicus may have an even greater opportunity in scaling the number of acquisitions it can do in a year than Constellation had at the time. The European VMS market lends itself to fragmentation, consisting of many local leaders. Because every European country has different languages and regulations, it’s not easy, in management’s own words, for a given vertical to cross borders unless it follows its clientele to another country.

Meanwhile, there are, ostensibly, fewer private equity dollars euros chasing acquisitions relative to the U.S. Part of it has to do with European culture. Because European businesses tend to be family-owned and oriented (TSS started from a family office by the founding Strikwerda family which is now Joday), selling to a perpetual owner like Topicus has more appeal than to let it go to a transient owner that aims to flip the business over to the next highest bidder half a decade (or sooner) into the future. In other words, reputation and permanent capital is arguably a greater advantage in Europe than it is in the U.S. I wasn’t able to find any data on private equity specifically targeting VMS in Europe (if you got any, please send them over), but there are permanent capital peers worth considering. Two include Vitec Software and Netcompany, both operating in the Nordics. The former can be compared to the Topicus Operating Group in which solutions are largely created in-house from scratch on the back of extensive innovation with the occasional acquisition carried out to strengthen the company’s existing capabilities while the latter is more like the TSS Operating Groups in which growth is pursued by acquisitions and good deals. Both approaches have worked, paving the way for further value creation in the European VMS market. Since November 2004, Vitec’s share price has compounded at +35% per year excluding dividends to a current market cap of SEK18bn. Netcompany’s stock has gone up 230% since IPO in June 2018.

The Topicus story seems like a plug-and-play model. Just copy over Constellation’s values, processes, incentive system, and culture to the more fragmented European market and you’re ready to go. But, of course, there are caveats.

Prospective investors should know that Topicus’ current capital and ownership structure is rather convoluted as a result of the spin off, making an analyst’s eyes pop if they were to look at the financial statements unbeknownst to how the transaction worked.

This requires some explanation. As part of the IPO, the three major shareholders, Constellation, Joday, and Ijssel, received convertible preferreds which paid a 5% dividend until converted. Last fiscal year, this dividend amounted to ~€60mn, taking up about half of adjusted net income. These preferreds were a liability on the balance sheet to the extent that they remained redeemable because the redemption price (of €19.06 per share) could either be settled in cash or stock. So at the end of each reporting period, the liability was marked to fair value with a redeemable preferred securities expense (or income) taken on the income statement. This is the reason why Topicus took a huge €2.3bn hit in Q1 2021 after the IPO which dragged net income down to a negative €2.4bn for the fiscal quarter. As the share price went up, the liability to owners of the preferreds went up as well.

Due to a forced conversion from the share price trading above a 25% premium to the redemption price (the “Mandatory Conversion Moment”), these will all be converted by February 1st, 2022, so that the annual preferred dividend disappears, the share count increases from a last reported 79.3mn (past quarter weighted average) to 129.6mn shares, and the liability moves to equity (which already happened at the Notification of Conversion). You can call this finalizing the transaction from which Constellation, Joday, and Ijssel will make a lot of money (which they would have anyway had they elected common stock, but now they got the annual dividend and the capital gain). The shares will be diluted but the annual preferred dividend will stop sucking up the company’s FCF.

So the capital complexity will soon fizzle out but private investors still won’t have much say in the business. Every member of Topicus’ board is appointed by the three major shareholders. Joday, the original Strikwerda family office, owns 30.3% of the fully diluted shares. Ijssel, the sellers of Topicus, owns 9%. Constellation owns 30.35%. This means that upon full conversion of the preferreds, the publicly traded float will only represent ~30% of the shares outstanding. Meanwhile, in addition to Constellation’s equity ownership, the company owns one Super Voting Share which grants it 50.1% of the votes.

But it’s not that big of a deal. Topicus is not Graftech—a company in which the minority will need to watch their own hand since they’re not playing the same cards as the majority owner, Brookfield Capital Partners. In Constellation, the minority can expect their interests to be aligned. Rather than damning the fact that minority rights are essentially absent, investors should ask themselves this: What if Constellation ends up divesting their stake and Topicus ends up losing all the great things that come with being owned by the greatest VMS capital allocator in the world? Wouldn’t that be a worse alternative?

A devil’s advocate might say there are other challenges worth mentioning. One is the possibility that the M&A VMS playbook can be/is becoming widely copied: seek specialized software assets that are market leaders, that are mission-critical, grows in markets below the radar of global software giants, has pricing power, manages costs well, and then buy more than one and let them share best practices. As Mark Leonard has said himself, there aren’t many barriers to entry in creating a serial VMS acquirer. All you need is a telephone and some capital. If sellers of assets start to become savvier about their potential value, with an increasing number of acquirers chasing the same deals, closing them at <1x price/sales might become a challenge and the window for extreme value creation in the VMS M&A playbook may slowly close.

Meanwhile, mass migration to cloud products is a challenge that all VMS incumbents face. And horizontal SaaS-native competitors—like the products built by Microsoft, Salesforce, and Atlassian—are getting better at addressing customers’ universal needs, at least of the collaborative kind. One can imagine a future in which vertical and horizontal software start to coalesce in certain industries. The long-term implication may be that VMSs cannot continue to rely on high on-premise switching costs and +90% retention rates (a trend which is already showing at Constellation). In the long-term, high switching costs may become harder to achieve and must be sourced from data, automation, and network effects rather than just being “mission-critical”.

Despite these challenges, it all looks like Topicus might have the upper hand on Constellation in terms of potential growth and returns, at least in the decade that follows. Like Constellation’s VMSs, Topicus’ existing businesses are resilient and the company has a strong competitive position in the M&A arena.

It is therefore no surprise that Topicus trades at a premium to its parent. At a CAD4.3bn market cap (~€3bn), €90mn of TTM FCFA2S generated, and added share dilution, Topicus trades at a fully-diluted ~50x trailing FCFA2S multiple. In my Constellation write-up, I rendered a 40x multiple too expensive given the company’s closing-ended opportunities and organic growth challenges. Topicus may not be. An investment in Topicus is an investment in the Constellation culture and strategy, almost with the clock reset on M&A and innovation capabilities from Topicus thrown into the mix. Whether that is a blessing or a constraint is yet to be seen. Nevertheless, Constellation has for almost the past decade consistently traded in multiple bands somewhere between 20x and 40x FCFA2S. At no time could you have bought Constellation at the top of the range and still not made a +30% compounded return.

It all comes down to the growth and stability in FCF. At 50x FCFA2S, you may only get a 2% yield, but slapping a decade of high, stable growth on top results in an inevitably handsome return, almost no matter the price you originally bought the stock at (consequently, any DCF you make on such a high-growth, fade-defying business is likely to be understated).

By the same logic, if Topicus was to steadily compound FCF by 15-20% over the next decade, does it matter much whether you’re getting a puny 2% FCFA2S yield today? It’s hard to ask any conservative value investor to skip the model and simply trust one’s qualitative assessment of the company’s excellence and gut check for the possible compounding runway. But true capital-light compounders require it, you see more of them popping up in the investing landscape as “software is eating the world”, and almost all of them look expensive by conventional thinking.